Derivations of words throw up some significant curiosities. I knew that a pedagogue was originally someone in ancient Greece who led a child around, including to school. The term then took a professional turn, to refer to the specialised function of instructing children. But I had never noticed the – to me now rather obvious – etymological similarity between “pedagogue” and “synagogue”.

Apparently, a synagogue was originally a secular place of assembly, where adult males came together to socialise, discuss and learn from each other. It later became exclusively identified as the place where Jews could come together to read scriptures.

So far, so mildly interesting. But think what might have happened if the original meaning of “synagogy” had developed into a general way of organising learning, as pedagogy did. We could have seen, from the outset, a network of adult education centres accepted as an integral part of any modern society, as schools and colleges now are.

In the event, however, pedagogy has – to put it crudely – stifled synagogy. The education of young people has swollen to dimensions that crowd out the chance of a balanced system of lifelong learning. Imagine instead that the public commitment, and the resources, had been put into learning for all: to synagogy. In the UK, the recent Augar review of post-school funding has provided a rigorous basis for just such a debate.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates annual up front government expenditure on higher education to be about £17 billion, and participation rates are approaching 50 per cent. But who has benefited from all this expansion, all these shiny new university buildings popping up everywhere?

Some graduates from some universities do very well, moving quickly into highly paid work. But it’s not at all clear how much that has to do with what they have learned, as opposed to the signalling provided to employers by the selectiveness of these universities. Many graduates do much less well, and some poorly.

I don’t want to do down higher education. My point is simply to ask what the opportunity costs have been of all that investment. Even 20 per cent of £17 billion would give us about £3.5 billion. What might the consequences have been had it gone into promoting synagogy rather than swelling pedagogy (with all due respect to university students, the “ped” part of pedagogy does increasingly apply to them, as mature students in England have largely drifted away in the era of high tuition fees).

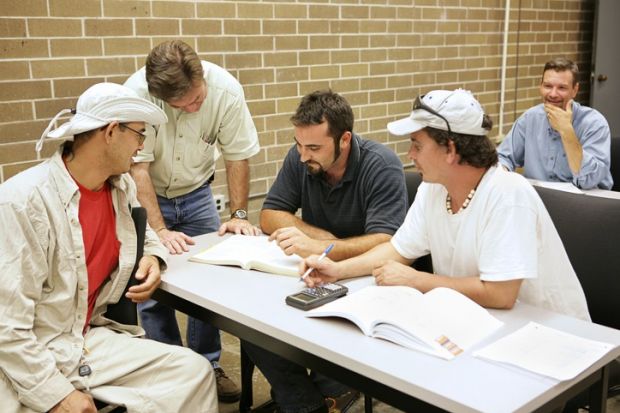

A big chunk of that £3.5 billion – perhaps half – could have been wisely invested in further education colleges, as Augar now advocates. But let’s say the remaining 10 per cent had been available for our secular synagogues. Imagine how many towns and villages across the country would now have well-designed local centres where adults could easily come to learn, sometimes from each other and sometimes from outsiders with the particular expertise or experience necessary to give the discussions shape and direction. How different the Brexit “debate” might have been, for instance, if older citizens had been educated and empowered in this way.

What more appropriate forum could there be to raise the level of civic debate? There, different generations might meet and learn from and about each other – with huge mutual benefits for our general health and well-being. The massive availability of online resources means that almost infinite content is there for the downloading. What is needed are spaces for these resources to be used collectively, with the proper professional support to make full use of the wonderful opportunities that new technologies offer.

This is the kind of balance that the Augar report opens up in prospect. What a missed opportunity it will be if, instead, it prompts only squabbles about the level of university tuition fees.

Tom Schuller is a visiting professor at the University of Wolverhampton and a former chair of governors at the Working Men’s College, London. He was the co-author of Learning through Life, the final report of the 2009 UK inquiry into the future of lifelong learning. His most recent book is The Paula Principle: How and Why Women Work below their Level of Competence.

后记

Print headline: Kosher learning