The leap in the share of students gaining first-class degrees in the UK in recent years has drawn increasing scrutiny as the questions over whether grade inflation is behind the rise mount up.

It is an issue that was brought back to the fore last week by the revelation that one university department discussed its low share of “good honours” and its league table position just weeks before dozens of student marks in the faculty were increased in a moderation exercise.

Universities UK is expected to publish a report on the issue soon as pressure from the government intensifies to find a way to stop the situation getting so out of control that virtually every student graduates with a 2:1 or first.

Now a data analysis from Times Higher Education reveals that a major part of the rise in the number of top degrees appears to have been driven by certain subject areas.

Three subject areas that together represented almost a third of all bachelor’s degrees awarded in 2016-17 warrant particular attention: business and administrative studies; subjects allied to medicine (a large part of which is nursing courses); and computer science, the category that covers the raised marks at Teesside University reported on by THE last week.

According to Higher Education Statistics Agency data analysed by THE, the share of firsts awarded in computer science across the sector climbed by 19 percentage points between 2007-08 and 2016-17, so that 35 per cent of all students graduating in 2016-17 received a first.

This was the highest increase of any subject area in the sector. On its own, this may not have had a huge impact on the sector average: only 4 per cent of bachelor’s-level degrees in 2016-17 were in computer science, which is also a category covering a wide variety of courses including computer games design and software engineering.

However, the two next highest increases were in subjects allied to medicine and business studies (both a 15 percentage point rise), areas that together accounted for a quarter of all degrees awarded.

As well as broader subject areas, THE also examined more detailed subject areas between 2012-13 and 2016-17. In the business studies area, it was hospitality, leisure, sport, tourism and transport courses that recorded the biggest rise in the share of firsts (discounting subjects with smaller cohorts): up from 14 per cent in 2012-13 to 24 per cent in 2016-17.

And within subjects allied to medicine, the narrow subject area of anatomy, physiology and pathology notched up a 12 percentage point rise, while pharmacology, toxicology and pharmacy rose by 10 percentage points, as did nursing.

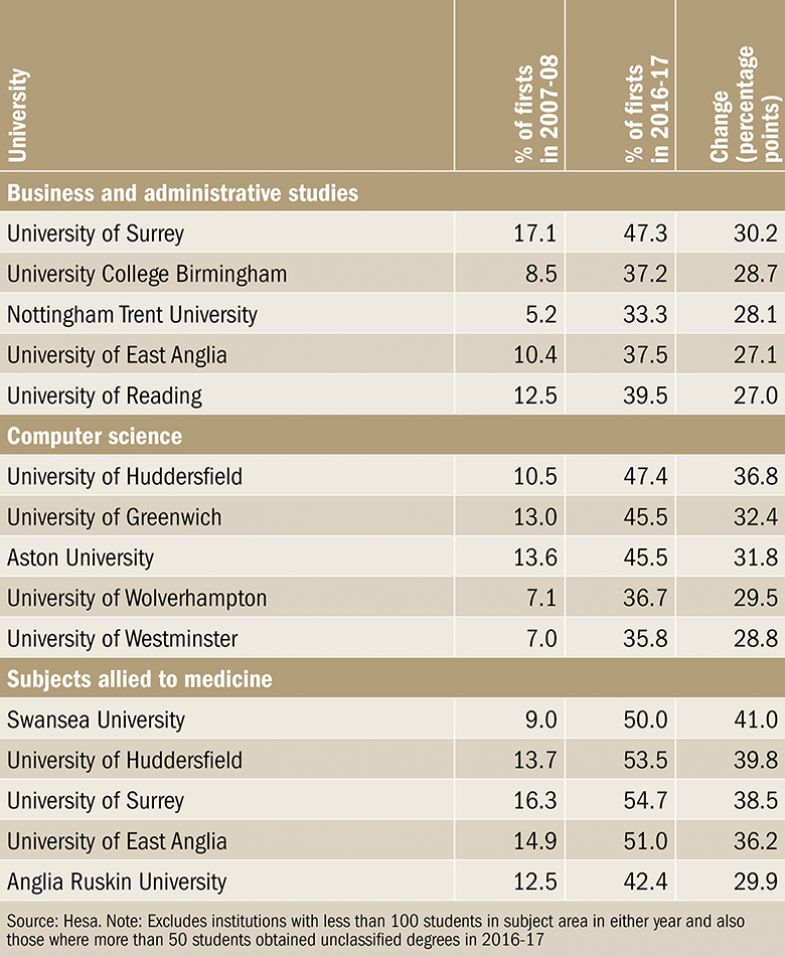

Some of the specific figures at individual universities are striking.

Swansea University recorded one of the biggest increases in the share of firsts between 2007-08 and 2016-17 in a particular subject area, with a 41 percentage point rise in the proportion of students gaining a top allied health degree over the period. It meant that half of students in the subject area graduated with a first in 2016-17, and the specific figures in nursing show that firsts awarded more than tripled from 50 to 155 from 2012-13 to 2016-17.

Ceri Phillips, head of Swansea’s College of Human and Health Sciences, said that the university’s nursing courses “enjoy an outstanding reputation and consistently score very highly in leading league tables. This is reflected in the significant rise in the number of first-class honours achieved in nursing.”

He added that “rigorous” admissions processes meant that “only the highest calibre of applicants” gained places, while the college had also “changed our degree classification calculation method, which has raised classifications in many cases”.

Swansea is also not an outlier. Nine other universities with large student cohorts recorded an increase in the share of firsts awarded to nursing graduates of 20 percentage points or more in the four years to 2016-17.

Big institutional leaps in firsts

It is a similar story in other, wider subject areas. For example, in computer science, the share of firsts climbed by at least 30 percentage points at six universities from 2007-08 to 2016-17.

Some of these figures look even stranger when they are compared with subject areas where the share of firsts rose, but not by nearly as much.

In three subject areas – law, languages, and historical and philosophical studies – the share of firsts grew by less than 10 per cent over the decade. As the three areas together represented less than 15 per cent of all degrees in 2016-17, their more moderate rise would have had less effect on the sector average.

It all raises the question: is there a common factor here explaining the subject differences? Could it be that the rises are higher in areas where there has been growth in the number of degrees? Does the employment market play a part in some way, given that, apart from law, the big rises are in subjects that lead to more defined work paths?

Volker Müller-Benedict, a professor at the University of Flensburg in Germany, who has studied grade increases over time in the country, has found that grade rises can happen in “cycles” and in some subjects they appear to be linked to fluctuations in the job market.

However, it may be hard to pinpoint any role played by the job market in UK subject areas without specific research.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, said that computer science was an interesting example because many graduates were entering the job market with degrees in the area while the industry itself was “saying that we can’t recruit the people we want”.

“This data – if you take it at face value – suggests that universities think that they’re churning out better computer scientists than they used to; but talk to any of the big employers of computer science graduates and they say they can’t find the skills they need,” Mr Hillman said.

Contrast this with modern languages, a subject that has declined in popularity in recent years but which Claire Gorrara, chair of the University Council of Modern Languages, said can offer “a rich and challenging curriculum requiring achievement in many areas”.

“This multidisciplinary approach may explain the depth and breadth of performance required to excel. It also explains why modern linguists are in high demand in sectors needing resilient, flexible graduates with applied workplace skills,” said Professor Gorrara, professor of French studies at Cardiff University.

Mr Hillman’s general view on the growth in the number of top degrees is that, whatever the factors behind it, they all could be bundled together in “a basket called competition” as universities increasingly benchmark against each other. It may just be, therefore, that some subjects have more competition for students than others.

But Paul Ashwin, professor of higher education at Lancaster University, said that although the drive to perform well in league tables had “definitely played a large role in grade inflation”, that “doesn’t explain this subject difference”.

He said that it might actually be down to “the ways these different subjects are assessed” and whether “students can get closer to 100 per cent or equivalent on assignments”, although the algorithms used to convert these to a final degree classification were also important.

“Marks of 100 per cent are more likely in tasks that involve mathematical calculation than tasks that involve the development of a written argument. This would seem to fit with some of [these] examples,” Professor Ashwin said.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

后记

Print headline: Inflationary subjects: the small set with a big impact