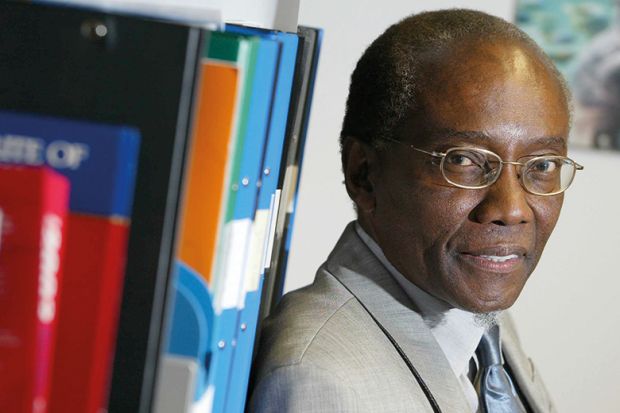

Sir Godfrey Palmer, known as Geoff, was the first black professor in Scotland and discovered the barley abrasion process, subsequently adopted by the UK’s biggest breweries. His education in the UK started at a secondary modern school, before his cricket talents landed him a place at Highbury County Grammar School. He went on to a degree in botany at the University of Leicester and a career in grain science. Now emeritus professor in the School of Life Sciences at Heriot-Watt University, he recently featured in the Scottish government’s We Are Scotland campaign, which “celebrates the contribution people from overseas make to Scotland’s communities, economy and culture”.

When and where were you born?

St Elizabeth, Jamaica, in 1940. As a child, my mother took me to live in Kingston. When my mother sailed to London on the Mauritania in 1948, I lived with her sisters in Allman Town in Kingston until I left Jamaica in 1955 for New York, from where I sailed on the Ascania to Liverpool. I took a train to Paddington station to meet my mother, whom I had not seen since 1948. I did not recognise her, she recognised me. My mother, to earn the £86 that she had paid for my fare from Jamaica to London, worked in various menial jobs in London from 1948 to 1955.

What did you think of Britain when you arrived as a 15-year-old and how were you treated by people?

When I arrived, I was somewhat concerned with being confined to the single room in which my mother and I lived and sharing the kitchen, bathroom and toilet with different people who I did not know. I was indifferent to white people who moved out of my way on the pavement, women who shifted their handbags just in case I might steal them, and those who wanted to touch my hair. These irritating incidents have declined significantly but I recalled them briefly with a smile when recently a white person on a railway station asked me to carry luggage to a taxi.

What was your first experience with the British education system?

My mother took me to the local comprehensive in Highbury and I was designated “educationally subnormal”. I did not understand the questions. One was about Big Ben. I thought that Big Ben was a large man.

Between 1969 and 1971, you wrote a series of articles in the Times Educational Supplement about the education of West Indian children in British schools. What impact did they have?

In the articles, I said that ignorance of British West Indian culture [in British schools] is a major reason why many West Indian children fail in the educational system. I also pointed out that children were fulfilling the low expectations that the system had of them. The education system, like the racism of politicians such as Enoch Powell, was damaging these children. I still believe that, without a sense of belonging, children will fail to realise their potential. Because of these articles, I was invited to attend various conferences, which resulted in many [British] teachers travelling to the Caribbean to learn something about Caribbean culture.

How would you explain your field of grain science to a member of the public?

In my book Cereal Science and Technology I state that “technology is science that works”. This statement explains why science matters. For example, it was believed that it was the germ that produced most of the enzymes that changed the growing grain into malt. The science of my work indicated that it was the bran that produced most of the enzymes, therefore it is the bran that should be stimulated to accelerate the malting process. The abrasion process worked because it stimulated the bran. In lectures to my students, I try to make it clear that scientific understanding provides the potential to improve technology; better science makes better medicines; better science makes better beer.

What were the worst examples of racism that you encountered in your academic career?

In terms of racism towards me, [one of a number of incidents that] I remember well is: in 1964 when a well-known politician was on an interview panel for a higher degree, he told me to go home and grow bananas. I responded that it was difficult to grow bananas in Haringey.

What has Heriot-Watt University meant to you?

Heriot-Watt has been “home” to me since December 1964 when I was accepted by Anna MacLeod to study for a PhD. Anna said that she saw some potential in me that was not reflected in examination scores. At Heriot-Watt, I helped to set up the International Centre for Brewing and Distilling with funds from the brewing and distilling industries. I am very proud of the students who gained their qualifications from this department, and I proudly buy the products that they produce.

Why did you want to be part of the We Are Scotland campaign?

Historically, the Scottish people, like other people of these islands, have had a significant influence on the lives of the people of Jamaica and other British colonies in the Caribbean, especially during slavery. This link is important to me because it also adds to my sense of belonging; a belonging that says, this is a part of my home. This campaign is a positive way of changing the cruelties and prejudices of the past into positive ways forward.

What keeps you awake at night?

At 78, I often worry that I will forget all the information that I need to give requested lectures to the community. My mother used to say that I could lose my way home.

What do you do for fun?

Sample a beer or a dram and note how fast my grandchildren are growing. In short, I am the product of £86, and love and support from family and good people I have met during my life.

john.morgan@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Claudine Gay has been named the next Edgerley family dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. Professor Gay, Wilbur A. Cowett professor of government and of African and African American Studies at Harvard, has been the university’s dean of social sciences since 2015. Professor Gay said that it was “hard to imagine a more exciting opportunity” than leading a community that was “diverse, ambitious, and deeply committed to teaching and research excellence”. Harvard has also named Bridget Terry Long, Saris professor of education and economics, dean of the Graduate School of Education.

Sarah Sharples will be the University of Nottingham’s first pro vice-chancellor for equality, diversity and inclusion. Professor Sharples, currently associate pro vice-chancellor for research and knowledge exchange in Nottingham’s Faculty of Engineering, will be tasked with tackling challenges such as the academic gender pay gap. Professor Sharples, who will take up the role on 1 September, said that she aimed to “develop a strategy to ensure that all are helped to do their very best in supporting an inclusive culture”.

Paul Fieldsend-Danks has been named academic dean at Plymouth College of Art. Mr Danks, who was previously head of the graduate school, will play an important role in the institution’s attempt to secure taught degree-awarding powers and, eventually, university title.

Lorraine Frazier will join Columbia University’s School of Nursing as dean on 1 September. Professor Frazier, who will also take on the titles of Mary O’Neil Mundinger DrPH professor of nursing and senior vice-president of Columbia University Irving Medical Center, joins the New York institution from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Kristin Weyman has been appointed associate dean for undergraduate students at the California Institute of Technology. She joins from Ohio Wesleyan University, where she was associate dean for student success.