Recent weeks have seen a sudden outpouring of concern for the future of the Open University among UK politicians and the media.

There is little doubt that the distance-learning institution faces serious challenges: its student headcount has declined by a third in the past seven years and the institution has reported multimillion-pound deficits in three of the last four years.

As the institution's future is hotly debated, many commentators have pointed to the countless mature students the OU has helped by offering them a chance to gradually retrain or study for a degree while working.

However, a close look at the data around student numbers at the institution over the past decade suggest that England’s 2012 higher education funding reforms – frequently blamed for the OU's current woes – have already drastically changed such a model.

According to the Higher Education Statistics Agency figures, the like-for-like student population at the OU has not changed that much over the past decade. In 2005-06, there were the equivalent of about 64,000 full-time students studying at the OU, very similar to 2016-17 (when full-time equivalent numbers were almost 62,000).

However, undergraduate numbers have plummeted by a quarter, from about 151,000 in 2005-06 to a little more than 113,000 last year.

Underlying this is a major shift in the profile of students on OU courses and the way they study.

For instance, the number of FTE students studying for a “first degree” – the equivalent of a bachelor's qualification – with the OU went up by 35 per cent from 2005-06 to 2016-17 from about 39,000 FTE students to just over 53,000 in 2016-17. Such students now represent 86 per cent of the OU’s FTE student cohort, up from 61 per cent in 2005-06.

At the same time, the number of “other undergraduates” – those studying at sub-degree level – has fallen almost 70 per cent during the period and made up 10 per cent of FTE students in 2016-17 (down from almost a third in 2005-06).

This may suggest that a lot fewer students are using the OU as a way to build credits at sub-degree level without necessarily committing to a full degree.

Such a finding would tally with data analysed by Claire Callender, professor of higher education at Birkbeck, University of London and the UCL Institute of Education, for a Sutton Trust report she co-authored earlier this year.

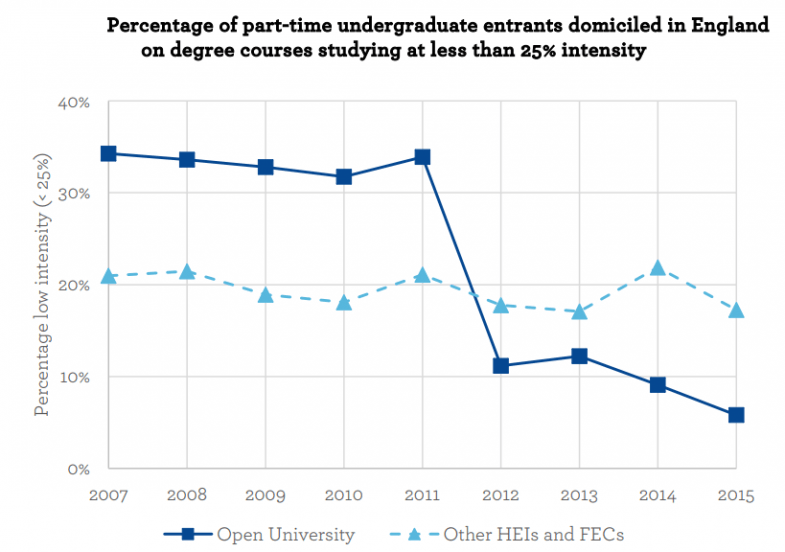

That report showed how another dramatic change in the OU’s student cohort after 2012 has been a huge drop in the share of part-time undergraduates studying at less than a quarter of the rate of a full-time student.

Around a third of the OU’s undergraduates had studied this way prior to 2012, but became ineligible for loans after the reforms, as the rules stated they must be studying above 25 per cent intensity and be on a course that leads to a qualification.

“It looks, quite understandably, as if they [the OU] have tailored their provision so that students are eligible for loans,” Professor Callender said.

“That affects the nature of the courses. One of the classic OU models was that an individual wouldn’t sign up for a degree at the start of their studies. They…built up credits and came in and out of study. The student loan rules and regulations and eligibility criteria don’t allow that.”

Even if students are eligible for loans, they face much higher fees than the institution used to charge (per English FTE student, average annual fees went up to £5,000 from £1,400 in 2012) so will take on a significant debt. Taken together, it is a model that is likely to be either unobtainable or unattractive to older people at a stage in their life when they have considerable financial commitments such as a family and a mortgage.

So nostalgic calls to save the OU’s position as the “university of the second chance” may be harking back to an era that has already been lost.