Knowledge and power are intimately related. Some of history’s biggest atrocities began when someone powerful asked someone else if they would mind collecting some data – specifically, making a list of names.

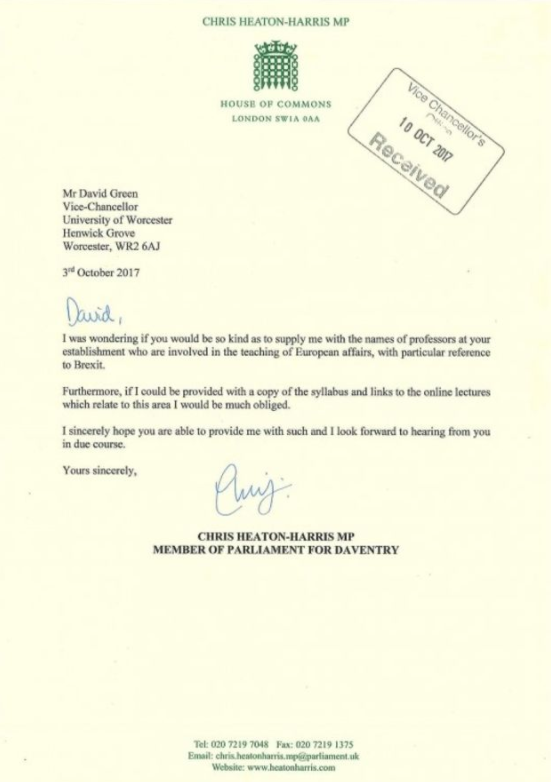

So when Chris Heaton-Harris, a government whip, writes to every vice-chancellor in the country asking if they would mind sending the names of all academics involved in teaching about Brexit and provide links to their course syllabuses, most – although interestingly, not all – academics felt moved to protest.

More than one vice-chancellor immediately passed their copy of the letter to the press. The Member for Daventry soon found himself trending on social media amid accusations of intimidation and references to Foucault, Lenin and Section 19 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights.

Did academics overreact? After all, some interpreted the request as innocent (“he’s just trying to do his job”); cheeky (“he should do what he expects everyone else to do – pay £9,250 and go on the course”); misdirected (“the average v-c won’t know this information anyway”); or downright stupid (“doesn’t he know how to use Google?”); as well as perfectly within the law (“isn’t this what FOI [Freedom of Information Act] is all about?”).

I was struck by comments that the Heaton-Harris letter was nothing more than a “polite request for information”. True, the letter was positively dripping with politeness:

I sent it to some colleagues who specialise in critical discourse analysis.

One said:

“The scary ‘linguistic’ thing going on here is the pretence that this letter is a mitigated and therefore innocent directive. ‘I was wondering if you would be so kind [as to do something unthinkable]’, ‘if I could be provided [with content which I expect to be anti-Brexit]’.”

Politeness is not merely a social convention. In the language of discourse analysis, hedging “does work”. As another colleague commented:

“It appears to pay respect to a senior person, but the demand formality in terms such as ‘supply me with’ shows these politeness terms up for what they are – a way of covering the demand tone without losing its functional force.”

The text, as oh-so-politely expressed, will – to quote a professor of linguistics – “offer him ‘plausible deniability’ of heavy-handedness”, a phrase that aptly captures how the Leader of the House, Andrea Leadsom, rushed to the writer’s defence, telling the BBC: “It does seem to me to be a bit odd that universities should react in such a negative way to a fairly courteous request.”

What one of my sources described as some unusual lexical choices (such as asking for “the names of professors” when in reality most teaching is done by non-professors), his assumption that the information will be readily obtainable and his view of university teaching as the supply of static course materials indicate the writer’s lack of familiarity with the environment that he potentially seeks to police.

Various awkward turns of phrase (“I was wondering if…”, “you would be so kind as”) suggest that the writer is aware that he has low entitlement to the information he seeks. When someone who a) has low entitlement to information and b) is aware of that low entitlement makes a request, it would be expected that they will carefully explain and justify why they want the information and what they plan to do with it.

Yet this crucial contextual information – “the author is a hard Brexiteer; most academics are Remainers. The author is very unlikely to be interested in ‘the field’, he is more than likely interested in [identifying] those who are against Brexit” – is strikingly missing.

Given this context, the absence of reassurance that the information requested will not be used in something resembling a witch-hunt adds to the menacing tone of the letter.

One of my sources wondered whether the letter was deliberately written in order to be leaked, since “it doesn’t matter what it says, what matters is that it has been written. For now we know about it and we can wonder what ‘field of teaching’ the powers that be will be concerned with next.”

Whether or not this was the case, a detailed scholarly analysis of how Mr Heaton-Harris phrased his polite request adds weight to a recent Guardian editorial. It suggested a sinister progression of a post-referendum culture war in which universities are depicted as liberal conspiracies out to brainwash the nation’s youth, and hence (implicitly at least) in need of some form of state censorship. No wonder the University and College Union talked of “the acrid whiff of McCarthyism”.

Reassuringly, many academics were moved to speak out. Three hours after seeking to clarify his actions on Twitter (“To be absolutely clear, I believe in free speech in our universities and in having an open and vigorous debate about Brexit”), Heaton-Harris had notched up more than 1,600 replies, of which my favourite was: “Excellent. So you’ll be working very hard for the release of the Brexit impact studies?”

Perhaps we should all now write and ask the Honourable Member to do just that.

Trisha Greenhalgh is professor of primary care health sciences at the University of Oxford. She wishes to thank Dariusz Galasinski, Deborah Cameron and three others who preferred to remain anonymous.