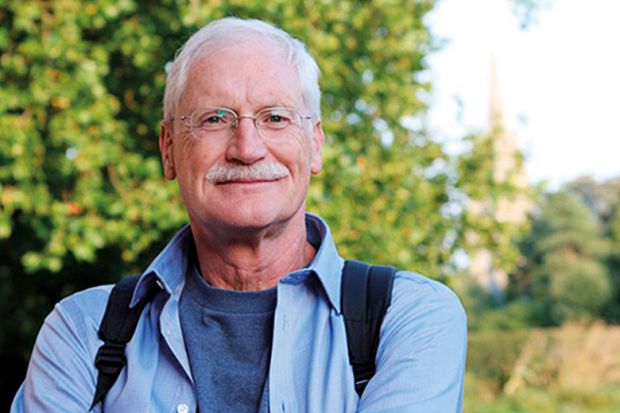

Wolfram Schultz is professor of neuroscience at the University of Cambridge. In March, he was the joint recipient of the Brain Prize, awarded by the Lundbeck Foundation in Denmark. At €1 million (£853,000), it is the most valuable prize in the field, recognising those who have made vital contributions to understanding how human brains work. Professor Schultz and co-winners Peter Dayan and Ray Dolan from University College London were awarded the prize for their analysis of how the brain recognises and processes reward. Their research built on discoveries made by Professor Schultz 30 years ago.

Where and when were you born?

I was born in eastern Germany, and in a year that I won’t reveal because of the age discrimination at universities that tries to force-retire their professors.

How has this shaped you?

Growing up after two world wars in the centre of Europe was a fantastic experience. Everybody was fed up with the attitudes and prejudices of these ridiculous European countries that could not get along with their neighbours, out of which we created the European Union, which over the years matured into a success story with 500 million people from more than 20 countries. We learned foreign languages, travelled around Europe freely for almost no money, learned that the different cultures were not all that different in the end, and simply could not understand how our parents believed in all these prejudices and referred to other countries as enemies.

What is the significance of winning such an award?

A huge personal satisfaction. When one discovers something, there are often more sceptical people than supportive people; with such a prize, the supportive people have won, and their faith in our work has come to a positive resolution. And that is a huge satisfaction and support for my laboratory members, who trust in my suggestions. Of course, with all the crazy ideas for theories and experiments, I ask myself frequently whether I am on the wrong path. But I just continue nevertheless – then suddenly, “bang”, and there is a clear result with consequences that become slowly visible – and appreciated. The point is to not listen too much and to just go ahead and do what you think looks interesting.

You have worked in Germany, the US, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK. How crucial has the freedom to work in different countries been to your research?

Some people do well in a single country, like the old scientists in the times of parochialism and nationalism, but other people like the stimulation of more distant colleagues and their ideas. The latter would not thrive as well if the boundaries were stricter, and I am one of them. I like the exchange of ideas; the fact that I am now doing neuroeconomics is due to the easy and productive exchange with colleagues who are often far away. Of course, the wandering scientist can also become unfocused and without a home, but that seems less of a real problem overall.

What concerns do you have about the implications of Brexit on the European research landscape now that Article 50 has been triggered?

[There will] not [be] much impact for the European research landscape, but [there will be] less easy migration to the UK and less financial support here. Also, the generous grants provided by the European Research Council may no longer come (and the money paid in by the UK may be used for something else). I had such an ERC grant for five years, which allowed me to do several high-risk projects that I would have never dared to do with my regular funding. Now, even the last of these projects works, and we will focus more on this daring but feasible research direction. Sometimes an only relatively small difference in support, manpower and money can make a huge difference between running standard projects (which are good and necessary but not milestones) and conducting a truly novel project with implications that are unknown at the time they are undertaken. We don’t want to miss these chances.

What is the worst thing anyone has ever said about your academic work?

The usual stuff: I don’t believe your data. What can you say, invite them into your lab? Apart from that, people have criticised, ridiculed or put into question several of our findings, less the key ones than the ramifications, but some were pretty annoying.

What keeps you awake at night?

Nothing really. But I often wake up at night with an idea in my head, usually something I have been discussing, reading or thinking about in the days before. That is a good time, as everything is quiet, and I can slowly and without time pressure think it through and come to some conclusion – I sometimes even take notes. This happens maybe two to three times a week: very beneficial.

What kind of undergraduate were you?

I began as a university student after two years of military service. My brain was like an empty sponge. University was fantastic, a world full of knowledge and very interesting people. I studied medicine and went to philosophy lectures as much as I could, and then mathematics until my medical exams came up.

What brings you comfort?

Good ideas, carefully thought through; good discussions at home and with friends and colleagues; beer.

What saddens you?

Wasting time, the many people on the street with visible brain disorders, warfare, Brexit.

If you were the higher education minister for a day, what policy would you immediately introduce to the sector?

Abolish student fees, totally. And abolish age-related mandatory retirement and replace it with financially attractive voluntary retirement. Some people are happy to do other things at some age, but others – like me – cannot stop what they like doing.

john.elmes@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Julie Hall has been appointed deputy vice-chancellor of Southampton Solent University. Professor Hall, currently deputy provost (academic development) at the University of Roehampton, takes up her position in August. She has been a member of the government’s expert panel on teaching excellence since 2014 and has also served as chair of the Staff and Educational Development Association. She said that she was looking forward to the role, having for some time admired Southampton Solent’s “distinctive culture and its focus on high-quality student learning”. There was, she continued, “a genuine commitment to enhance the university’s strengths in teaching and research and to forge innovative partnerships”.

Amy Conley Wright has begun her work in the new role of director of the Institute of Open Adoption Studies – a joint venture between the University of Sydney and Barnados Australia, funded by the New South Wales government. Professor Wright will lead the institute in its mission to investigate evidence-based pathways to a safe home for life for children who have been permanently removed from their parents by court order. “We have a historic opportunity to deliver policy and practice-relevant research to support permanency outcomes for children in care,” she said. “In this work, we will be guided by the views and lived experiences of children, young people and their families.”

Gordana Vunjak-Novakovic has been made a university professor, Columbia University’s highest academic honour. Professor Vunjak-Novakovic is currently Mikati Foundation professor of biomedical engineering and director of Columbia’s Laboratory for Stem Cells and Tissue Engineering. Gary Gillespie, chief economic adviser to the Scottish government, Alexandra Jones, director of industrial strategy at the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, and John Pullinger, national statistician at the UK Statistics Authority, are three of 47 leading social scientists who have been awarded fellowships of the Academy of Social Sciences.

后记

Print headline: HE & me