"Science communication” is a buzz-phrase that has recently gained considerable traction in the groves of academe, along with calling students “customers” and trying to market degrees like new cars. It all sounds very modern, but this fascinating book explains why it is not. Even the most remarkable idea can fail to prick public consciousness without some decent PR: the landmark sweet pea experiments conducted by Gregor Mendel, the Austrian monk and “father of genetics”, which were largely ignored until well after his death, might be the most obvious example.

Which brings us to the excitement generated by two animals – one living, one fossilised – separated by hundreds of years and thousands of miles. In 1515, a live rhinoceros was packed into the hold of a Portuguese ship in India and sent off to Lisbon; 274 years later, the skeleton of a Megatherium was dispatched from South America to Madrid. The Megatherium was a genus of giant sloth found across South America until the end of the Pliocene epoch; at 4 tonnes, it was one of the largest ground-dwelling mammals ever. And the rhinoceros was, well, a rhinoceros. These two tales may seem, in the grand scheme of things, like insignificant events. However, as becomes clear in historian of science Juan Pimentel’s compelling account, there are strong connections linking the two, with the reaction to the Megatherium strongly influenced by the arrival of, and reaction to, the rhinoceros more than two centuries earlier.

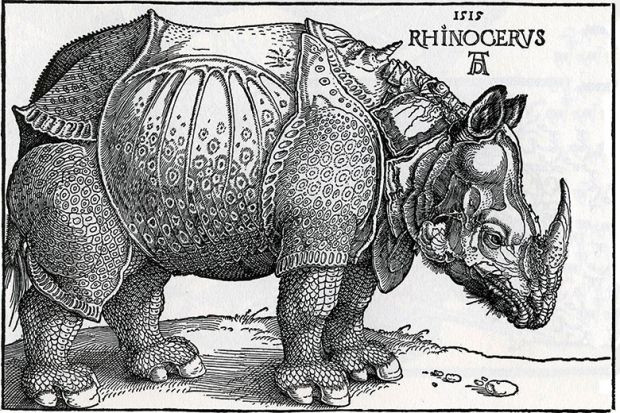

Collecting exotic beasts had long been a favourite activity of kings and emperors, from the menageries of Roman circuses to Frederick II’s penchant for animal parades and the many beasts, real and imagined, that adorn a thousand coats of arms. This was the role that the titular rhinoceros was lined up to play for Manuel II of Portugal; alas, en route, the ship sank in the Mediterranean with all hands. That would have been the end of the story but for the work of Albrecht Dürer, one of the outstanding natural history artists of the age. The ill-fated animal in question became known as “Dürer’s Rhinoceros”, not because he discovered it or even studied it, but because his woodcut illustration became a best-seller.

What is extraordinary is that Dürer had not actually seen the rhino in question – or indeed any rhino – but relied instead on second-hand accounts. Unsurprisingly, it was not an especially good likeness. Although the horn is plausible enough, it looks like someone has strapped a set of armour on to a rather grumpy pig – and given the length of time that the poor animal spent in the ship’s hold, its mood is probably the most accurate part of the woodcut. Of course it is easy to scoff at Dürer’s best-guess version, surrounded as we are by high definition pictures and video at the click of a mouse. Images are key to our understanding of science, and this rhino’s ill-fated adventure coincided with the start of the scientific Renaissance, when the image began to assume great importance as a central component of knowledge. A bad picture of a rhino Dürer’s may have been, but it was arguably the first example of the mass consumption of science.

The scientific world into which the Megatherium skeleton arrived in 1789 had been shaped by the earlier events in which Dürer’s woodcut played a key part. Unlike the rhino, a living animal, the Megatherium was a fossil skeleton unearthed in a land that would have seemed almost unimaginably distant from Europe. The bones of the giant sloth were packed in crates in South America and shipped to Spain as an unknown species of giant monster to be wondered at by the public and pondered over by natural philosophers. Here, the link with Dürer’s rhino might seem to be at its most tenuous. But Pimentel’s skilful argument shows that the role of illustration as a tool of scientific dissemination that began with the rhino bore fruit here. Illustration and publication had by this stage become the scientific norm. Images of the fantastic creature were sent around Europe and crossed the desk of pioneering palaeontologist Georges Cuvier, who correctly deduced that the bones belonged to a giant sloth.

It is not overstating this moment to describe it as one of the most important in the development of the study of prehistory. While 1789 is famous as the year the French Revolution began, the scientific developments at the time would prove at least as significant as its social and political upheaval. Cuvier’s identification of the fossil as a giant sloth helped to lay the groundwork for casting aside the prevailing paradigm that viewed the Earth as young and species as the unchanging work of a creator. When the Megatherium arrived in Europe, the two Charlies who would shake the world with their work – Charles Lyell, whose Principles of Geology established the geological antiquity of the planet, and we all know what Charles Darwin did – had not yet been born. But the bones of a long-dead creature helped to establish the scientific world in which their theories flourished.

In the prologue, Pimentel rather brilliantly describes his book as a “historical essay with a tentative and slightly provocative character” (for which praise must be shared with Peter Mason, for his excellent translation). And if that isn’t a wonderfully tempting hook for the reader, then what is? The Rhinoceros and the Megatherium is part detective story reconstructing the scientific process, and part historical study of how people reacted to the hitherto unknown and unusual. The parallels drawn by Pimentel are beautifully constructed and drip from the page like honey: a section describing the sea voyages of the fossils mirroring the political and intellectual shifts of the periods is especially effective. Yet perhaps the most important aspect of the story is not the animals but the role played by Dürer’s woodcut: an image derived from the descriptions of others that nonetheless went “mainstream”, assuming a life of its own as it travelled throughout Europe and across the Atlantic, taking with it ideas about science and communication. As Pimentel suggests, its transmission is one of the earliest examples of globalisation. It is an elegant concept without doubt, but throughout the book it struck me that Dürer’s rhinoceros was much more like a modern-day internet meme, produced without too much concern for detail or accuracy and tossed out into the world to be shared at will.

On the subject of giant ground-dwelling sloths, I have fond memories of visiting the Cueva del Milodón in Tierra del Fuego many years ago on fieldwork. If you happen to be passing, do take the opportunity to visit, as it contains a life-sized model of a Mylodon, a cousin of the Megatherium. It is often singled out in guidebooks as being rather naff, and it is, but gloriously so. This model in a remote Argentine cave lingers in the memory in the same way as Dürer’s woodcut, and thus speaks to the importance of visual representation in science. Pimentel’s book concludes with a very balanced assessment of what it set out to achieve: a comparison of two events separated by hundreds of years. The author is rather unsparing in his assessment of his own work, observing that he has made the effort to draw parallels and make links, but leaving us with the suspicion that he may not be wholly satisfied. In this Pimentel should not be concerned. He has adeptly and eloquently brought back to life not only these two much-marvelled-at beasts but the minds of the people who sought to explain them and the worlds in which they lived.

Simon Underdown is senior lecturer in biological anthropology, Oxford Brookes University.

The Rhinoceros and the Megatherium: An Essay in Natural History

By Juan Pimentel Translated by Peter Mason

Harvard University Press, 368pp, £22.95

ISBN 9780674737129

Published 26 January 2017

The author

Juan Pimentel is associate professor at the Institute of History in the Centre for Humanities and Social Sciences (CCHS) at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC, the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas) in Madrid.

Born a Madrileño, he has “always lived in Madrid, apart from two years I spent at the University of Cambridge as a visiting scholar (1994-96) at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science. There, I worked under the supervision of Simon Schaffer, a true master and a leading figure in my field.

“Of course Madrid has shaped me as a person. It is a cosmopolitan city, halfway between Southern and Northern Europe, lively, warm, endowed with a bustling cultural life (including good food, and football).”

Pimentel recalls growing up in a home “full of books: history, literature, economics, art. I liked to study, and to go to school too (most of the time). I liked people and friends (now I prefer friends to people). I became interested in the history of science while working on my PhD, and, after, in Cambridge, when I realised how sophisticated and interesting it could be as a subject, and to have the opportunity to rethink the things you take for granted.”

As an undergraduate, he was “a hard-working student at the Complutense University [of Madrid], and ambitious in the sense that I have always read on many topics. Not too solitary (I think I am sociable) but neither gregarious: I hate tribes and group dynamics (this is the worst part of academic life, by far).”

Does he think that Albrecht Dürer would feel embarrassed that his drawing of the rhinoceros was inaccurate, or proud that it is still famous today?

“Dürer would have realised that the original would resemble the copy, and that nature does its best to imitate art (as Oscar Wilde sharply noticed).”

Apart from those two years at Cambridge, Pimentel has spent his whole academic life at the CSIC, which he compares to “the French CNRS, hosting different institutes ranging from biomedical to physical and even social sciences and humanities”. He took up his first post, a four-year predoctoral fellowship, at the Institute of History in 1989.

The CCHS was created a decade ago, he observes, in “an effort to unify the humanities and social science research institutes at the CSIC. In Spain, we are used to changing labels, departments, academic structures; we are very innovative! But it would be pretentious to say that I decided to work at the CSIC. You apply for a first fellowship when you are very young, and then life takes its course.”

What has the CCHS accomplished?

“It was a nice project, undertaken at a time of expansion and general optimism. Now, things have changed. You need more than a decade to create a milieu such as that of Princeton University, or Cambridge. Ramón y Cajal, the Spanish histologist and Nobel laureate, used to say that the history of Spanish science was a succession of the sudden starts of a horse and the abrupt stops of a donkey. We are going – I’m afraid – through a donkey moment (which, however, seems to be a global trend).”

Pimentel continues: “The CCHS was an endeavour intended to coordinate all the different and previous institutes of humanities and social sciences. We also moved to a shared space, a big building, on the outskirts of Madrid, with a huge library formed by the sum of the dispersed libraries. But now this wonderful library, the heart of the CCHS, is almost empty, because we are far from the university’s campus, and young students don’t cross the city nowadays in search of (paper/traditional) books. The CCHS has not only an Institute of History (where I work, and which is the biggest of its institutes) but also an Institute of Philosophy, another of Philology, Language and Anthropology, and so on. There are about 500 of us working in the CCHS.”

Asked about his next endeavours, Pimentel replies: “I’m currently involved in two projects. First, an exhibition of maps at the Spanish National Library, which I am curating alongside a colleague, Sandra Sáenz-López, an expert on cartography. Second, a book on images of Spanish science – a vast period, as it includes examples ranging from the 16th to the 21st centuries. The aim is to search for different images (plant illustrations, photographs, prints, fossils, canvas, still-lives), treated as ‘ghosts’. I am interested in the afterlives of the images, the link between phantom and image, but I am also dealing with the discontinuity, the vanishing nature of Spanish science. Science is the ghost that haunts Spanish culture. Nobody denies the existence of Spanish literature or art. But science is a problematic and contested presence in our tradition.”

If he could could change one thing about the academy in Spain, what would it be?

“The persistence of nepotism, which leads to the rule of mediocrity,” says Pimentel. “Last week, for instance, at the University of Madrid, a candidate with 10 years of experience at the University of St Andrews in Scotland was rejected for a post of assistant professor…there was an internal candidate! At the CSIC, sadly, it is pretty much the same.”

What gives Pimentel hope?

“Our students, the young researchers. They are well trained, polyglot, international, resilient and creative. All of us have former students abroad, in the UK, and in the US. Perhaps, thanks to Brexit and President Trump, we will get some of them back. Every cloud has a silver lining.”

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: A woodcut is worth a thousand words