Placed amid industrial shelving racks lined with boxes, the elegant bronze bust of Francis Galton stands out from its cramped surroundings in an obscure 1960s annex of University College London near Euston station.

The statue of the eminent UCL scientist – hailed as the “father of fingerprinting” and a Victorian trailblazer of genetic science – is one you might expect to find displayed as prominently as the “auto-icon” of Jeremy Bentham, UCL’s spiritual father, which greets visitors to one of its main campus buildings. Apart from his scientific legacy to the university, Galton also bequeathed UCL £45,000, funding a professorial chair that still bears his name.

The location of the Galton Collection – a collection of his scientific artefacts that can be viewed by appointment – actually owes more to departmental rejigs than institutional embarrassment. But the likelihood of a move to more prestigious environs seems low given that Galton is also the high priest of eugenics and is increasingly known for some of his racist opinions, such as the idea articulated in an 1873 letter to The Times calling for the “good-tempered, frugal, industrious” Chinese to “supplant the inferior Negro race” in Africa.

Some students and staff have also called for UCL’s Galton lecture theatre to be renamed. And even the Galton Collection’s curator, Subhadra Das, is unwilling to defend him: “You can’t excuse those opinions by simply saying Galton was a man of his time. While many prominent thinkers of the day supported eugenics, many said he was wrong when he published these views,” she says.

UCL is by no means the only university to be presented in recent years with difficult decisions about the balance to be struck between respecting their history and promoting their modern values. A growing tide of opinion, particularly among students, takes the view that the latter goal is more important – and that buildings, statues and other items honouring those who do not live up to modern moral standards are a positive hindrance to meeting it.

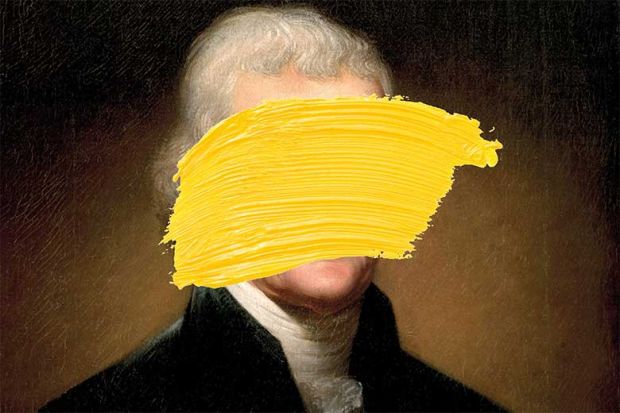

Feelings are particularly strong around the issue of race. In August 2015, a bronze statue of Jefferson Davis, the slave-owning Confederate president during the American Civil War, was removed from a prominent position at the University of Texas, Austin, and is due to be placed inside the university’s refurbished American history centre next year. In December 2015, students at the University of Missouri and at William and Mary in Virginia covered statues of Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the US, with yellow sticky notes labelling him “racist” and “rapist” on account of his relationship with one of his own slaves.

Earlier this year, Amherst College in Massachusetts dumped its mascot, Lord Jeff, based on the 18th-century military commander Lord Jeffrey Amherst, whose troops handed out blankets deliberately laced with smallpox to Native Americans. And, in March, Harvard Law School agreed to retire an official shield based on the family crest of Isaac Royall, a brutal slave owner who endowed the university’s first law professorship.

In the UK, two memorials commemorating visits by King Leopold II of Belgium were quietly removed by Queen Mary University of London in June “as part of ongoing refurbishment” after a student campaign. Queen Mary said the inscriptions suggested a “strength of association [with the Belgian ruler] that was never the case”. The strength of feeling arose from the fact that Leopold’s imperial ambitions in the 19th-century “scramble for Africa” are said to have caused the death of about 10 million people in the Congo.

But the most well-known controversies have revolved around the 19th-century British mining magnate and imperialist Cecil Rhodes, who regarded Africa – where he made his fortune – as being “inhabited by the most despicable specimens of human beings”. The Rhodes Must Fall campaign began at South Africa’s University of Cape Town in March 2015, with the aim of removing the statue of Rhodes that loomed over the institution’s campus.

Martin Hall, a former deputy vice-chancellor at Cape Town who later led the University of Salford, believes that the university authorities were right to act swiftly on the demands.

“We have an obligation to listen much more to students,” says Hall, who described the Rhodes Must Fall campaign’s linking of modern-day grievances to historical injustices as “extremely clever”.

“When faeces were thrown at the statue, people outside South Africa probably didn’t realise that this was indexing other protests going on at the time over poor sanitation in poorer neighbourhoods, but everyone here understood the political message,” says Hall.

Universities should see the removal of controversial statues and memorials as part of the natural evolution of their campuses, adds Hall. “University campuses are not museums or mausoleums – they are living environments, where new buildings are built all the time. They have to be vibrant, and that means listening to students.”

That was not the position, however, ultimately taken by the University of Oxford’s Oriel College, which rebuffed calls to remove a small statue of Rhodes from above one of its entrances in January 2016, after the Rhodes Must Fall campaign spread there from South Africa.

At the time, Ntokozo Qwabe, a South African Rhodes scholar who co-founded the Oxford movement, told the BBC he felt “the same way [about the Rhodes statue as] I would feel if I saw a statue of Hitler in Germany”. And Tadiwa Madenga, a Zimbabwean student at Oxford, said the statue reminded her of the struggles her family had had in colonial Rhodesia. “We’ve lived in places where we’ve seen the consequences [of colonialism] and it still deeply affects us, this kind of memory of British imperialism.”

Oriel had earlier agreed to act on such sentiments and remove a plaque marking the room Rhodes had occupied as a student because his views on race were “inconsistent with our principles”. But its statement announcing its final decision said it had received an “overwhelming message” in support of keeping both the plaque and the statue. So rather than removing them, it would “seek to provide a clear historical context to explain why [the statue] is there”. This would “help draw attention to this history, do justice to the complexity of the debate, and be true to our educational mission”. The statement did not address newspaper claims that donors had threatened to withdraw gifts and bequests worth more than £100 million if the statue was removed.

David Priestland, professor of modern history at Oxford, agrees that such a contextualising approach “is important if we are to encourage discussion of our imperial past and improve public understanding. As surveys show, many British people have a rather rosy view of their imperial history, and that can have political consequences. For example, imperial nostalgia was an important part of the Brexit campaign.”

In Priestland’s view, the controversies over statues “are related to the issue of public memory and how we understand our history; they aren’t about free speech and censorship, as much of the commentary at the time of the Rhodes Must Fall campaign wrongly claimed”.

For Kalwant Bhopal, professor of education and social justice at the University of Southampton, “pulling down a statue is a symbolic and political act but this in itself is not enough. It must be related to making changes in the social structures and dismantling the processes of white privilege in universities.” Where that wider process is lacking, removing the statues can potentially be premature because “having them there reminds us of history and that we need to challenge it and debate it”.

But, in an excoriating open letter published earlier this month, the Rhodes Must Fall campaign accuses Oriel of being “pushed” by donors’ threats and of disrespecting the “students and faculty of colour, who have spoken clearly to say that the statue of Cecil Rhodes contributes to the University of Oxford being an unwelcoming and hostile space”. It questions whether Oriel acted on a previous pledge to establish lectures on race equality and colonialism, and to fundraise for scholarships for Africans – but adds that such measures still fall short of “any real recognition” of Rhodes’ “brutalities, killing, raping, expropriating and legal exclusion of Black people in Southern Africa”. It calls for an Oxford-wide “commitment to address colonial iconography”, a “decolonised curriculum” and “representation for people of colour at all levels”.

At UCL, Das believes any “whitewashing” of history would prevent a wider discussion about how science fed into Europe’s colonial project, with often horrendous results. Studying Galton’s methods and ideas within their social context can help students to understand how a well-meaning scientist can arrive at wrong-headed conclusions, she adds.

“He wanted to improve society – he saw thousands of extremely poor people in inner cities who were suffering and he wanted to improve these conditions,” she says of Galton’s work to examine personality through physical tests, such as height, weight and handgrip strength. “Where Galton went wrong was to say people are in poverty because of their nature, rather than social conditions.” This focus on nature over nurture progressed into the study of racial difference; the resulting “institutionalising racism in science” was used to justify colonial aggression and, later, Nazi genocide.

Stephen Trachtenberg, president emeritus at George Washington University, which he led for almost two decades until 2007, also believes that the drive to erase morally compromised historical figures from modern campuses is wrongheaded.

“It is not to downplay the evil that happened in the 19th and 20th century, but we need to retain a certain modesty about how we would have acted in those circumstances,” he says. “We should not turn [honoured figures] into magical figures either, but we need to recognise them fully as human beings, some of whom were better and some of whom were worse than us.”

The revulsion felt towards the slavers who made financial contributions to early US universities should not lead to a blanket condemnation of their lives and works, says Trachtenberg.

“Slavery is the original sin of this republic and it is something we still need to address, but it does not follow that people who owned slaves could not do good things,” he says, citing the financial legacies that later paid for many students to attend university. “Do we say we will never read the poetry of Ezra Pound because he sided with Mussolini and held anti-Semitic views? No – we look at his body of work and say we may not like his political views but he added to the sum of human knowledge.”

The challenge, for Trachtenberg, is to learn from history so that “everyone can look back on the 21st century with greater pride” than we can on previous centuries.

That learning process has been particularly evident in recent times at Princeton University, where a 10-member special committee spent six months examining the legacy on campus of the US’ First World War-era president Woodrow Wilson – also Princeton’s 10th president before he entered politics – who was a firm supporter of black segregation. The review followed a campaign in 2015 to rename Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, culminating in a student occupation of the president’s office.

“My first instinct to this [proposal] was ‘right on!’,” Brent L. Henry, the black vice-chairman of the university’s board of trustees and chair of the review committee, told an audience at Yale University in September. “When I was a student, there were 13 black men at Princeton and we all knew about Wilson’s legacy and we had no idea that anyone would care if that legacy was important to us.” Modern naming controversies are “symbolic of the fact some students did not feel they belonged” at Princeton, he added.

Henry’s committee ultimately decided to retain Wilson’s name on buildings, but recommended other steps “to make sure everyone on campus feels like they belong”. These include moves to “diversify campus art and iconography to reflect the diversity and inclusivity of today’s Princeton”.

A similar reappraisal of the titans of Australian academia is taking place at the University of Melbourne, where several buildings bear the names of early 20th-century pro-eugenics scientists. The Richard Berry building for maths and statistics, for instance, is named after a head of anatomy who exhumed 400 bodies from traditional Aboriginal graves as part of experiments designed to “breed a better race”, and who lobbied for “sterilisation, segregation and the lethal chamber” for Aboriginal people, homosexuals, poor people and prostitutes.

Melbourne is committed to “acknowledging and engaging with our historical legacy as a colonial institution in a settler nation”, according to Ian Anderson, the institution’s pro vice-chancellor for engagement and an Aboriginal Tasmanian. As part of plans to “build an intellectual environment which is inclusive and respectful of indigenous Australian perspectives”, Melbourne will undertake a new set of initiatives in 2017 aimed at everything “from encouraging further discussion about place names at our campuses to building thought-leadership on these issues by hosting an international symposium on the colonial legacy of universities”. This, he hopes, will “ensure not just robust discussion but chart a comprehensive path forward towards a more inclusive campus”.

For Tom Cutterham, lecturer in United States history at the University of Birmingham, such controversies “should make us question the entire practice of putting up statues to individuals, naming buildings after them, and so on”. In his view, new buildings named after controversial donors should raise as much concern as historical statues. “At the end of the day, they’re all part of the same process of using institutions of culture and learning to legitimise and celebrate the profits of destructive and unethical practices,” he says.

Some Melbourne staff and students have called for more university spaces to be named after Aboriginal pioneers, such as Margaret Williams-Weir, Australia’s first Aboriginal graduate, who had a postgraduate lounge at Melbourne named after her in September 2015. Princeton’s new Committee on Naming is also aiming to name more buildings and spaces to “recognise individuals who would bring a more diverse presence to the campus”.

Even such well-meaning initiatives are not without controversy, however. For instance, eyebrows were raised when, in 2007, the University of Salford named its health and social care building after Mary Seacole, sometimes described as the “black Florence Nightingale”. Many hailed the move as an important recognition of the Jamaican-born Seacole’s heroism during the Crimean War, and a long-overdue recognition of the thousands of black and ethnic minority nurses working in the National Health Service today. But some historians believe the move was misguided because Seacole was not actually a nurse. They argue that she set up what was in essence a hotel, where she sold traditional Creole herbal remedies to wounded soldiers with mild maladies.

“There are many things to celebrate about Mary Seacole – she was a successful black entrepreneur, an independent woman, but she was not a nurse,” says Robert Dingwall, a professor in the School of Social Sciences at Nottingham Trent University. Her proximity to the battlefield, on which she helped on several occasions, was also nothing unusual at the time, given the large entourage of wives, families and traders that would accompany armies in the 19th century, he adds.

Salford’s building and, more egregiously, the £500,000 statue of Seacole in front of London’s St Thomas’ Hospital unveiled in June 2016, do a disservice to the contribution of black nurses by honouring someone with no connection to the profession, Dingwall believes.

“It’s understandable for the nursing leadership to do this, given previous problems with racism in the profession, but universities should be pushing back on this sort of thing as it ends up honouring the wrong people for the wrong reasons,” he says.

Faced with such fraught issues, university leaders could perhaps be forgiven for throwing up their hands in despair – before perhaps passing on the issue to a committee to grapple with. But, for Trachtenberg, “a committee is a way to kill a proposal or spread responsibility for a decision so thinly that it has no substance or responsibility”. And although “there are occasions when a committee is just the ticket for actually getting to consensus”, the role of university leaders is ultimately to lead – on difficult decisions as much as easy ones.

However, he believes it is important to listen to all constituencies on such controversial topics: the “soloists” as well as the “chorus”, however loud the latter might be. Nor can a university leader “ignore the costs, financial, political, social” of a decision to remove a statue or change a name: it is important to consider “what the institution will gain or lose in reputation and donations”.

“But equally compelling is the moral view,” Trachtenberg concludes. “What is the right thing to do? And, of course, let’s not forget that universities are teaching institutions. More important than erasing the past is to confront it, teach it, improve the present and set the stage for the future.”

Problematic heritage: how universities have atoned for their role in slavery

When Brown University president Ruth J. Simmons established a steering committee in 2003 to examine how the Rhode Island institution had benefited from slavery, the historic significance was unmissable. Simmons, whose paternal grandfather was descended from West African slaves, was the first African American president of Brown and the first black leader of an Ivy League university.

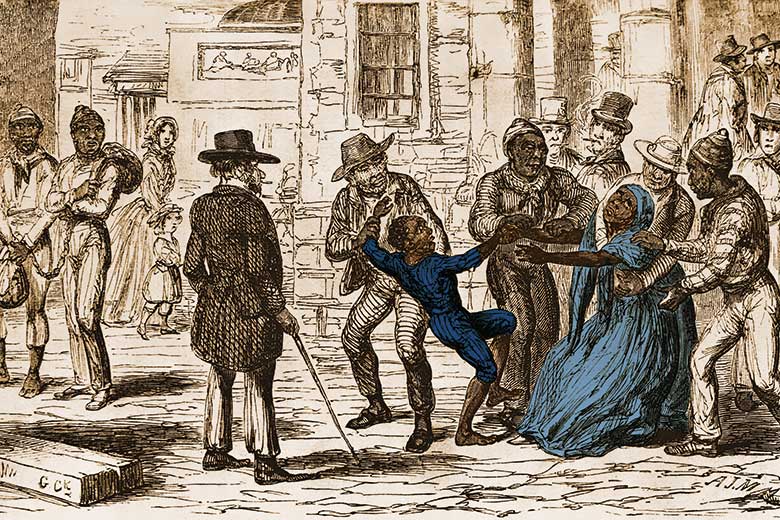

But another historical resonance was largely overlooked. Francis Wayland, a president of Brown in the pre-Civil War era, had been one of the leading anti-slavery voices of the day, writing that the institution “violates the personal liberty of man as a physical, intellectual and social being”. This was at a time when there was strong support for slavery among US universities in both the North and South, explains Alfred L. Brophy, Judge John Parker distinguished professor of law at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. Indeed, according to Brophy’s new book, University, Court and Slave, southern universities and their faculties owned slaves, profited from their labour, brutally punished them on campus and fought the emancipation movement with fervour, using history, philosophy and law to depict slavery as supported by natural law.

To atone for its slave legacy, Brown University created a $10 million endowment in 2007 to help poor local children to reach university, and other universities are now taking similar steps. In September, Washington DC’s Georgetown University said it would offer preferential status in admissions to the descendants of slaves, nearly two centuries after the Jesuit college profited from the sale of 272 slaves in 1838. It also created a slavery study institute and public memorial.

Some historians have called on UK universities to follow suit and acknowledge their links to slavery. While the University of Bristol gained its royal charter in 1906, almost a century after the slave trade was outlawed in 1807, its first main benefactor, the Wills family, imported slave-grown US tobacco up until the end of the Civil War in 1865.

“We have no public monuments recognising the contribution enslaved Africans made to the prosperity of the city of Bristol,” says Madge Dresser, associate professor of history at the University of the West of England, who in 2001 published a book, Slavery Obscured, on the subject.

“Though slavery has attracted increasing academic attention, mainly from left-leaning researchers, since the 1960s, it was not until the 1990s the issue really came to the surface in the public arena in Bristol,” she explains. In her view, both the city and its oldest university have been reluctant to face up to their past in this area.

By contrast, the “problematic heritage of Liverpool” with regard to slavery is “central” to the work of the University of Liverpool’s Centre for the Study of International Slavery, according to its co-director, Alex Balch. The centre has carefully probed how much the university, established in 1881, benefited from the wealth acquired by the slave-trading residents of Abercromby Square’s lavish townhouses, several of which are now occupied by the university.

But Balch believes that a more pressing issue is whether universities are benefiting from modern-day slavery. “It can be quite banal stuff – procurement in construction or whether building firms are using illegal gang labour, where abuses of human rights akin to slavery have occurred,” he says. “If universities are outsourcing lots of labour, they should know much more about these subcontractors and how they treat staff further down the supply chain.”

后记

Print headline: Sins of the fathers