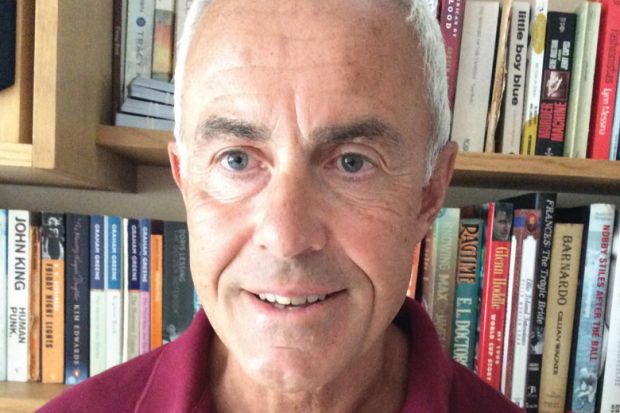

Dick Hobbs is an urban ethnographer and emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Essex. He specialises in the sociology of London and organised and professional crime, among others things. In June, he was awarded the British Society of Criminology’s 2016 Outstanding Achievement Award in recognition of his major contribution to criminological research and education.

Where and when were you born?

Plaistow, East London, 7 July 1951.

How has this shaped you?

It is at the root of everything that I have done. Reminders of the Second World War were inescapable in the East End. But the area had full employment for the first time, and when the 1960s rolled around the place was buzzing. The docks were thriving, goods were falling off the back of lorries, and pubs were packed. I had a very vivid childhood within a culture that valued wit, sharpness and the ability to earn a living against the odds. The place still fascinates me.

What were your immediate feelings upon discovering that you had won the award?

Amazement, embarrassment, celebration. On a loop. My aim as an academic has always been to do good work and earn a living. This prize is a real bonus.

You took a circuitous route to academia. Tell us about it.

I tried a number of low-paid clerical jobs, which I truly hated, and then spent a few years as a labourer, dustman and road sweeper. One summer, I worked as night porter at Eton. Eventually, I went to night classes for O levels and an A level (I got an E). I worked as a teacher [and] eventually, when I was in my thirties, I went to the London School of Economics and fell in love with the library. I got a grant [from the Economic and Social Research Council] to study for a PhD at Surrey, and went on to work at Oxford, Durham, the LSE and Essex.

You’ve been honoured for helping working-class students overcome the barriers they encounter at university. Are these barriers still apparent in UK universities?

“Non-traditional” students should be given the confidence to hit the same standards as the rest of the student population. If not implemented carefully, special provision can be counterproductive. Working-class students need to be respected, not patronised.

Your academic research into crime is informed by first-hand experience during your youth in East London (perhaps the symbolic home of British organised crime). What were those experiences?

Crime was normal; the docks generated a lot of stolen goods, and the trade was relatively open and public. It was part of everyday life, not the prerogative of some exotic underworld. Violence was also normal. The older generation were quick to “raise their hands” in the event of some dispute, and for my age group, the possibility of getting your head kicked in or worse was always pretty high. I became a very fast runner.

Organised crime is often lionised in popular culture. Does this paint over its insalubrious aspects or does it, at the very least, help bring it to wider society’s attention?

Since the early 1990s, “true crime” has become big business in the UK. As most contemporary organised crime is concerned with mundane, relatively benign trading relationships, it is much easier to appeal to a glamorous invented tradition of a glossy, picaresque underworld. We know more about what was on the jukebox in the Blind Beggar [pub in East London] when Ron Kray shot George Cornell [in 1966] than we do about the banal workings of contemporary, unlicensed capitalism.

Your research has the potential for danger. Have you ever been in any hairy moments with criminals?

One or two, but the most chilling threat I received in my academic career was when a senior manager at the LSE said, “We want you to be head of the sociology department for one more term.”

Do you sometimes walk along the streets of Spitalfields and wonder at how it has changed so dramatically from those days?

My dad worked in Spitalfields for 49 years, and I worked there for a while in my twenties. It used to be a magical, semi-derelict place of Dickensian pubs, warehouses, small workshops and lock-ups. It was not trendy, and the only locals with bushy beards and no socks were meths drinkers. I loved it. It is now an expensive, fashionable annex of the City of London. I hate it.

What is the biggest misconception about your field of study?

That organised crime is a terrain populated exclusively by “characters”. A cocktail of The Godfather, The Wire and Only Fools and Horses mixed by Guy Ritchie.

If you weren’t an academic, what do you think you’d be doing?

Laurie Taylor’s butler.

What has changed most in higher education in the past five to 10 years?

Often with the collusion of third-rate academics who should be regarded as little more than quislings, it has become populated by gangs of administrators and managers.

What is the worst thing anyone has ever said to you?

“Are you Old Bill?” “If you publish your PhD, you will never work again.” “Sam Allardyce is the new manager of West Ham.”

What keeps you awake at night?

Having wasted my time on any administrative or managerial task.

What’s your biggest regret?

Wasting my time on any administrative or managerial task.

What advice do you give to your students?

If you find the writing of an academic incomprehensible, perhaps they are lousy writers. You are not stupid.

What’s your most memorable moment at university?

Not exactly a moment, but when I turned up to register as a student at the LSE I was so nervous that my wife had to accompany me, otherwise I would never have made it. I have never forgotten the terror that university life can inspire. I now realise that universities are places where few people really feel they belong, including the staff.

Appointments

Gillian Douglas has been appointed the new dean of King’s College London’s Dickson Poon School of Law. Professor Douglas, currently professor of law at Cardiff University, will take over from David D. Caron in spring 2017. Her role will involve continuing to build the school’s reputation as a global leader in transnational law and global governance. Previously head of Cardiff’s law school, Professor Douglas has also served at the University of Bristol and at the National University of Singapore. “I am delighted and honoured to be appointed as dean, and look forward to working with colleagues in such a successful and dynamic academic environment,” she said.

Richard English, a leading scholar in Irish and British history and politics, has been appointed pro vice-chancellor for internationalisation and engagement at Queen’s University Belfast. Professor English, a fellow of the British Academy and a member of the Royal Irish Academy, will take up his role in September. He joins Queen’s from the University of St Andrews, where he is director of the Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence. “I’m very excited about the prospect of taking up this role at Queen’s,” he said. “It will be excellent to work with Queen’s colleagues as the university delivers its pioneering research, its invaluable teaching, and its many other societal contributions.”

Lisa Mooney has taken up her role as the first pro vice-chancellor for research and knowledge exchange at the University of East London.

Gianmario Verona, professor of management at Bocconi University, will become rector of the institution from 1 November.

The University of East Anglia has made three senior leadership appointments. Karen Jones, the founder of Café Rouge, has been appointed chancellor. Former chair of Ford Britain Joe Greenwell becomes the chair of UEA’s council. And Mark Williams, former partner at Deloitte, has been made the university’s treasurer.

后记

Print headline: HE & me