Brazil is the top performer in a new pilot Times Higher Education ranking of the best universities in Latin America.

The country claims half the top 10 places – with the University of São Paulo and the State University of Campinas in first and second place, respectively – and a total of 23 positions in the 50-strong list, more than any other country.

Chile is the second most-represented nation; led by the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile (in third position) and the University of Chile (fourth), it takes more than a fifth of places (a total of 11). Mexico also has two representatives in the top 10 – the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (eighth) and the National Autonomous University of Mexico (ninth) – and eight altogether.

The top 10 is completed by the University of the Andes, Colombia.

The ranking reveals a more diverse higher education playing field in the region than is visible at the worldwide level, with seven countries featuring in the list.

- Rankings data collection depends on institutions’ cooperation

- Chance for Latin American higher education to shine

- Best universities in South America

Carolina Guzmán-Valenzuela, researcher at the Centre for Advanced Research in Education at the University of Chile, said that Brazil’s success in the ranking reflects its high research outputs, high production of patents, and high research and development spending as a proportion of gross domestic product (1.15 per cent) compared with its regional neighbours, such as Mexico (0.426 per cent) and Chile (0.363 per cent).

Javier Botero Álvarez, who leads the World Bank’s tertiary education portfolio for Latin America, added that Brazil’s public universities have two attributes that enable them to excel within the region: large amounts of funding from the state and selective student recruitment.

However, he said, growing student numbers without an equivalent rise in funding has been “an issue” for universities across the region “for some years”.

- Universities in Latin America must join the global current

- Latin America should make a virtue of its diversity

“The amount of money universities receive per student is still low” compared with countries in other parts of the world, he said.

But despite this challenge, he predicted that institutions in Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Colombia will get “better and better” and claim more places in world rankings in the coming years.

The THE Latin America University Rankings use the same 13 performance indicators as the World University Rankings. However, there is less weight placed on citations as the research output threshold for eligible institutions was lowered from 1,000 to 500 papers over a five-year period to reflect lower publication volumes in the region.

Claim a free copy of the Latin America University Rankings digital supplement

Latin America University Rankings 2016: top 10

| 2016 Latin America rank | World University Rank 2015-16 | Institution | Country |

| 1 | 201–250 | University of São Paulo | Brazil |

| 2 | 351–400 | State University of Campinas | Brazil |

| 3 | 401–500 | Pontifical Catholic University of Chile | Chile |

| 4 | 501–600 | University of Chile | Chile |

| 5 | 501–600 | Federal University of Rio de Janeiro | Brazil |

| 6 | 501–600 | Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) | Brazil |

| 7 | 601–800 | Federal University of Minas Gerais | Brazil |

| 8 | 501–600 | Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education | Mexico |

| 9 | 401–500 | National Autonomous University of Mexico | Mexico |

| 10 | 501–600 | University of the Andes, Colombia | Colombia |

Browse the full list of the top 50 institutions in this year's rankings

What Latin America needs for rankings and development success

Jack Grove assesses the challenges posed by the region’s burgeoning student population and rapidly expanding higher education sector

With Latin America’s population set to rise by a quarter to 780 million people by 2050, higher education remains a priority for many of the region’s states.

Keen to maximise the potential of their youthful, ambitious and increasingly urbanised citizens, governments are driving forward with bold plans to expand university access, improve research quality and build links between industry and academia.

But what are the major challenges faced by Latin America as it seeks to build on 30 years of dizzying growth in student numbers and unprecedented sector change?

Meeting burgeoning demand for higher education in the face of economic instability – caused by the slump in gas and oil prices – is arguably the most pressing issue, says J. Salvador Peralta, associate professor and chair at the University of West Georgia’s department of political science, who researches Latin America’s higher education policies.

Venezuela’s extreme dependence on oil revenues – about half of state funds come from natural resources – makes it the most glaring example of this bind, says Peralta.

Some 80 per cent of eligible young people were enrolled in tertiary education in the leftist state until recently, up from about 30 per cent in 2000, the latest Unesco figures suggest.

“Given Venezuela’s constitutional commitment to provide free higher education for all, its current economic crisis is having a very detrimental impact on its ability to maintain that commitment,” Peralta says.

Brazil’s oil-led economic woes have also led to dramatic declines in higher education spending, with the region’s largest economy set to contract at least for the next few years, economists believe. That compares with the trebling of education funding to 94 billion reais (£18.5 billion) between 2003 and 2012, with higher education cash doubling to 28 billion reais (£5.5 billion) over the same period, he says.

“The country’s budget deficits will ensure that higher education funding declines, with more private providers entering the market to supply an increase in demand,” says Peralta.

Other oil-rich states, such as Mexico, and mineral-dependent economies, such as Chile, have also suffered since the collapse in price of natural resources since mid-2014, and may emulate Brazil’s austerity measures, he adds.

However, the rise of for-profit providers has been one of the region’s big success stories, opening up higher education to millions of poorer students, many believe. Three-quarters of the 16,000 higher education institutions in Latin America are private, educating more than 50 per cent of its 24 million or so students – the highest proportion of any region in the world. In Brazil, there are roughly eight private providers for every one public provider (2,100 private, 287 public in 2012) compared with a 3:1 ratio back in the 1990s.

Keeping course quality and standards high with so many smaller private providers is a major challenge for the sector, particularly in the case of technical and vocational training, Peralta believes.

Others point to the need to ensure that Latin America’s elite universities keep pace with the excellence found elsewhere in the world, with just one institution – the University of São Paulo – making the top 300 of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2015‑16, in the 201-250 band.

As such, São Paulo tops our inaugural Latin America University Ranking, followed by Brazil’s State University of Campinas and Chile’s Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

Almost half the top 50 is taken up by Brazilian universities (which claim a total of 23 places), with Chile filling 11 places and Mexico eight. Institutions from Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru and Venezuela also feature in the inaugural list, released at THE’s first Latin America Universities Summit, in Bogotá, Colombia, on 6-8 July.

So how does Latin America seek to raise the standing of its universities on the global stage?

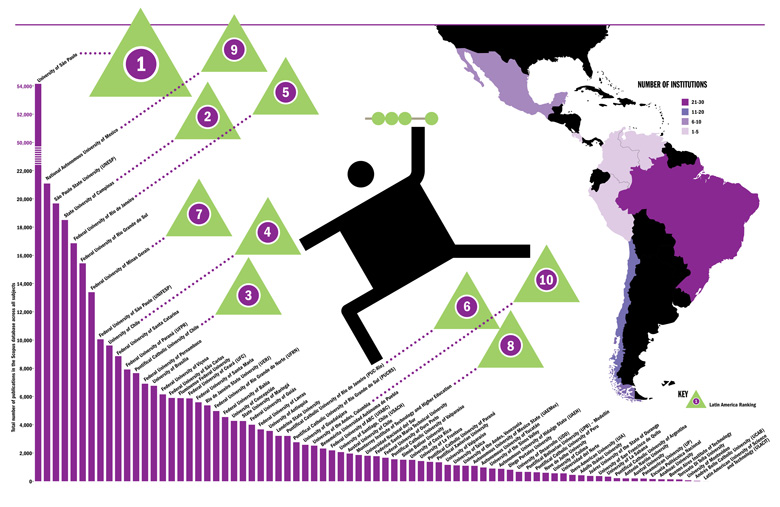

Latin America University Rankings 2016: Publication rates across the continent

The University of São Paulo stands out for its publication record, while the rest of the continent’s universities form a long tail when publication rate is looked at in Scopus

Beyond the obvious point of funding, some believe that the problems with Latin America’s universities relate to the foundation of those institutions in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

With the continent of South America, as well as Mexico, importing a Spanish model – highly influenced by the French – many elite universities have developed their courses along the “Napoleonic” tradition of higher education, based on training professionals rather than fostering broader scientific and scholarly enquiry, says Andrea Detmer, a former policy adviser at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile specialising in university-industry collaboration.

“In Latin America, we inherited from Spaniards and Portuguese the Napoleonic model, which is oriented to training professionals, and universities are state-controlled,” says Detmer, who is now a doctoral researcher at the UCL Institute of Education’s Centre for Global Higher Education. “In the Humboldtian model [found in Germany, the UK and the US], universities are oriented to science creation and, although they are state-dependent, an important value is academic autonomy,” she adds.

With little change to the Napoleonic model over the years, “long degree programmes based on traditional disciplines are still dominant”, meaning that higher education is expensive to fund for students, families and the state, Detmer explains.

In short, it means that the high cost of higher education is borne by the state or by the individual, she says.

“Some countries are strongly state-funded; others, like Chile, have an extremely privatised system, where some of the higher fees in the world are charged in state and privately owned institutions,” explains Detmer, who says that this has sparked a revival in the student movement in protest against exorbitant tuition fees.

Various governments need to increase the “extremely low level of research and development” spending in the region, Detmer adds, because this is “fundamental for the region’s long-term economic progress”.

“Industrial fabrics require more complexity and added value, through innovation, to counter-balance potentially reduced national incomes of natural resources-based economies,” she says.

“Universities can play an important role in boosting technological innovation, but research and development seems to be forgotten in the political agendas, with stagnated budgets and a private sector quite averse to innovation,” she explains.

Many commentators might add that Latin America’s universities also need to raise their research game, with less than 2 per cent of its 4,000 or so universities (two-thirds of which are private) publishing any research in internationally recognised journals between 2006 and 2010, according to an Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development working paper, “The rationale for higher education investment in Ibero-America”, released in August 2013.

As such, most higher education institutions are teaching-only, while others produce an “incipient or very low” level of research, the OECD paper says.

With university leaders, policymakers and higher education experts gathering at the THE summit in Bogotá, attention turns to the issue of rankings – in particular how to assess the merits of institutions in both a global and a regional context.

Thus the release of THE’s assessment of the region’s top institutions will start a consultation on how a future bespoke rankings for Latin America might be compiled.

This, in Detmer’s eyes, remains a key challenge for the region, which lacks good information that could help to inform policy across the entire continent and help to strengthen the area’s higher education system as a whole.

“We don’t have a Latin American Union and…only a couple of countries are OECD members, while some few others participate in their main studies,” Detmer says.

“Certainly not all are receptive to collaborations with the World Bank or the Inter-American Development Bank,” she says, adding that this “deficient comparable information limits research and policymaking with a regional view”.

With a free and frank exchange on what data should be used and how, the Latin America summit promises to provide an invaluable forum to hammer out just how policies and rankings to improve the region’s higher education sector might be achieved.