The epithets applied to Paris generally point in one, largely positive, direction – the City of Light, the capital of the 19th century, the capital of modernity, the city of love. In The Other Paris, Belgian literary scholar and critic Luc Sante has a mission – to rethink Paris as the world capital of contradictions.

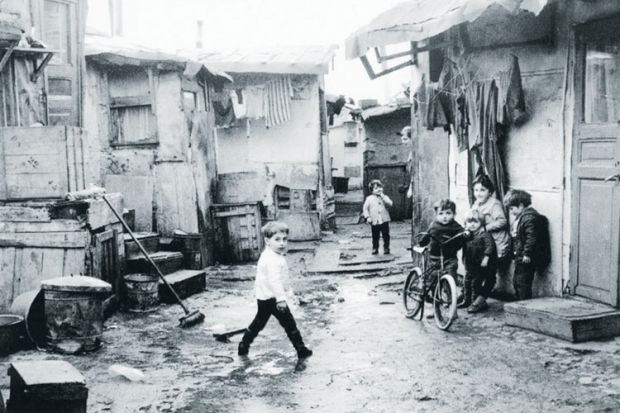

Sante’s argument is that today’s image of Paris displays continuity with the fashionable, artistic, wealthy, bourgeois lives of the past. Traces of the activities of the poor, the destitute, and those living outside society or kicking against authority have been all but eliminated by the processes of gentrification and urban change that began well before the activities of “Baron” Georges-Eugène Haussmann in the 1850s and 1860s, and carried on long after. For decade after decade, there has been a continuous erosion of the toeholds of “other Parisians”, most recently through episodes such as the demolition of the Halles market in 1971, and Nicolas Sarkozy’s 2003 law that removed street prostitution in neighbourhoods around rue Saint Denis. The 10th and 11th arrondissements, hit in last month’s deadly terrorist attacks, are examples of previously poor districts where marginal groups have been driven out by area upgrading, particularly through changes in the housing market.

Here, Sante aims to reclaim the histories of the poor, and of their neighbourhoods, and to contrast them with the more familiar histories of Paris. This is not totally uncharted territory – Louis Chevalier explored some of it in a 1958 study, published in 1973 in English as Labouring Classes and Dangerous Classes in Paris During the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. But Sante has produced a veritable tour de force by assembling a massive amount of material, much of it obscure, to examine wider aspects of the lives of the Parisian poor, and over a longer time period, than Chevalier covered. He has produced a volume from which even the most fervid collector of studies of Paris will learn much.

The spatial and temporal scope of The Other Paris shifts somewhat according to the topics that Sante covers, in part driven by the availability of material. His lens focuses most clearly on the century between 1840 and 1940, while the geographical extent of his interests generally expands with the growth of the administrative boundaries of Paris itself up to the zone surrounding the final fortifications of the city (now occupied by the boulevard périphérique). There are a few remarks on the post-Second World War creation of the massive suburban grands ensembles housing estates, although the interwar rash of poorly serviced self-build housing for those unable to afford Paris itself (the mal-lotis or “badly housed”) is not mentioned. But Sante’s analyses generally provide an extended temporal context within which his key period swims clearly into view.

The sources he draws on are impressively broad. Sante cites historical works from the 17th century alongside films from the 1930s, newspaper reports from the 19th century alongside extracts from realist novels by authors such as Honoré de Balzac, Victor Hugo and Francis Carco. The blend of sources offers a reading not just of the Paris of the poor as it was, but also as it was imagined to be, and how it featured in the general understanding of the city. What emerges is the existence of multiple points of contact between the different classes in the city. Public executions, for example, brought all Parisians together, while prostitution involved cross-class transactions, as illustrated, for example, in Émile Zola’s Nana.

Sante’s “other Parisians” comprised a society with a surprising amount of differentiation. Among the rag-pickers and collectors of garbage, for example, there was a detailed division of labour, with some specialising in particular items discarded by the better-off, and there was a distinct social hierarchy, with rank passed on from generation to generation. Recycling was very much the order of the day for all the poor, with meat bones made use of up to four times, starting with bourgeois restaurants, passing on to street pedlars of weak soup, and sometimes ending with the bones being ground up for use in mortar. An army of occupations that today no longer exist had their own specific locations – mattress carders and fish-bait vendors by the Seine, sock darners and public writers on what is now Place Maubert, wash houses along the Canal Saint-Martin. Neighbourhoods had their own specialities, and most of the poor rarely ventured out of their own district, which frequently amounted to little more than a dozen street blocks. The most noxious of all districts was that along the River Bièvre, running down from what is now the Place d’Italie to enter the Seine opposite Notre-Dame: it is here that the tanneries were located. Although Sante doesn’t point it out, an indication of the extent of the “upgrading” of Paris in the late 20th century is the fact that François Mitterrand, while President of the Republic, continued to inhabit his flat in what is now the rue de Bièvre, on the site where Balzac set the drowning of a child in the slurry of poisonous river mud in his Comédie Humaine.

Sante’s chapters on housing, neighbourhoods, occupations and the crowd all provide fascinating insights, in a first half of the book that deals generally with the everyday. But the author’s real enthusiasm is for the more exceptional lives and periodic events in the lives of the “others” – the street entertainers, music halls, crime in its many manifestations, and relationships with the police. All of these are treated extensively in The Other Paris’ second half. The bridge between the two is a chapter on prostitution – “Le Business” – which may have involved as many as 34,000 women in the 1850s. Many music hall acts, singers and other performers were from impoverished backgrounds (with Édith Piaf a 20th-century exemplar) and their acts and songs reflected working-class attitudes. Criminal gangs were celebrated in popular culture, in part for their resistance to an authority that was seen to be more and more distant from the interests of the poor. Sante follows the careers of a number of performers, gangsters and anarchists, and ultimately suggests that their power to represent the Parisian poor back to themselves diminished rapidly from the 1930s onwards as the ineluctable processes of gentrification drove the poor out of the city.

There is arguably a follow-up to The Other Paris waiting to be written that examines the cultures of the suburbs of the Parisian agglomeration in more recent decades, drawing on authors of immigrant origin such as Mehdi Charef and Nacer Kettane, films such as La Haine, and depictions of grand ensemble life such as Christiane Rochefort’s novel Les Petits Enfants du Siècle and some of the early songs of Jean-Jacques Goldman. Perhaps Sante could take on that task next.

While the book makes extensive use of contemporary illustrations, it is unfortunate that many are over-reduced and the opportunity to draw fuller attention to detailed elements of photos by Charles Marville and Eugène Atget, and to 19th-century cartoons, has not been taken. The Other Paris was clearly written for a North American audience, and this European reviewer was baffled by expressions such as “went for the roscoes” or “had to have the latest flivvers”. But the greatest problem for academic users of Sante’s otherwise excellent study lies in following up sources, since the referencing system provides no indications in the main text and is dependent on the identification of key words in a voluminous set of page-specific notes at the end.

These, however, are minor criticisms of a major work that impressively achieves its aim of countering the views of Paris as a city of constant delight and progress.

Paul White is professor of European urban geography, and former deputy vice-chancellor, University of Sheffield.

The Other Paris: An Illustrated Journey through a City’s Poor and Bohemian Past

By Luc Sante

Faber & Faber, 320pp, £25.00

ISBN 9780571241286

Published 5 November 2015

The author

A journalist, critic and translator as well as visiting professor of writing and photography at Bard College in New York, Luc Sante was born in Verviers, Belgium, and emigrated to the US with his family when still a child.

A journalist, critic and translator as well as visiting professor of writing and photography at Bard College in New York, Luc Sante was born in Verviers, Belgium, and emigrated to the US with his family when still a child.

Verviers, he observes, was “a city with a textile industry dating back to the Middle Ages that largely died in 1950s and put everyone out of work. My father had a childhood friend who had married an American GI from New Jersey, which led to us emigrating there. But the promised job didn’t materialise and my parents hated the New World, so we went back to Belgium. But things there were no better. We yo-yoed this way over the course of four years before things worked out on the American side.

“Home was a Belgian bubble – my parents insisted on French at home, among other things – so I grew up with a foot in each culture. I am definitely Belgian in many respects: reserve, a certain saturnine distance, class consciousness, various tastes in food and drink, an affection for morbid scandal...”

Sante now lives “in a small city in the Hudson River Valley, about 90 miles north of New York City, in a neighborhood of century-old houses that is the most diverse – racially, culturally, and even economically – I’ve ever inhabited, although people don’t tend to mix. About half my time is spent alone, since my friend snapped after eight years in this small town atmosphere and now spends part of her time in the city. My son, who is now 16 and is my primary reason for living up here, divides his time between my house and his mother’s, out in the country. We've been dogless since our beloved mutt Medusa died of age-related causes three years ago. I don’t like not having a dog, but between the atomized state of the household and the fact that I travel a lot, it may be a few years until we can have one again.”

As a child, Sante “was always reading, although I had little patience for the classroom and did not excel in my studies. My father, who worked in factories all his life, had a professorial temperament and would have like to be a writer – in fact, he named me after the pseudonym he employed for his one published piece of fiction – and he always encouraged me to fulfill his dreams by proxy.”

Did America live up to his childhood expectations? “I was so young that my only real impression of the place before we got here was connected to Mickey Mouse, as retailed in the weekly French-language comic Mickey. When we came, all I wanted to do was see The Mickey Mouse Club on television, but it turned out to consist of silly teenagers wearing ears, and I was grievously disappointed. It was my first experience with corporate duplicity. But I was young enough to be open to experience, and enjoyed the back-and-forth across the Atlantic quite a bit. Given the serious gaps in culture and especially technology between the two continents then, travel seemed like time travel, which led to a lifetime of confusing time and space.”

Sante admits to “no apparent degrees”, as he did not complete his studies at Columbia University. This has, he says, influenced his approach as a lecturer. “I am empathetic toward students, and don’t expect things of them that I wouldn’t expect of my younger self – which doesn’t mean that I am indulgent, exactly, but that I make sure to remember that my class is not the only one they are taking, that I allow them sufficient time, that I mix my medicine with a bit of candy, and that I always make room for independent thought and expression. I love to be surprised by my students.”

Do any of his students expect to make a living from writing? And does he think any of them will?

“Some do. I warn them sternly. Things are very, very different from the way they were in the 1980s, when I first made my way in the world. I have a few former students who have succeeded in literary careers, but they all have actual jobs – in publishing or academia.”

After his time at Columbia, Sante worked as a clerk in Manhattan’s famously vast, idiosyncratic Strand Books. “I was the paperback department, all by myself, which means I was thrown every acquisition that was not a hardcover book. I learned an enormous amount about books and their history, and began building a serious library of my own.

“It was also a great time to be at the Strand, because what became known as the No Wave was more or less birthed by Strand employees, half of whom were in bands. The Cramps, DNA, The Contortions and Teenage Jesus and the Jerks all were represented among the staff. It was an exciting time. I produced four issues of a magazine most of whose contents were the work of fellow employees (it was, naturally, called Stranded). And of course, it was also a time when despite very meagre salaries we could all afford apartments in lower Manhattan, as well as fashionable clothes and a lot of carousing.”

Sante’s 1991 book Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York focused on the late 19th and early 20th century. Of the lives of the poor in New York and Paris, he says that “the differences are much greater than the similarities. One for which I’m grateful is the literary quality of the coverage of Paris. The New York lore, at least in the 19th century, overwhelmingly originates in the florid and sometimes completely invented journalism of that time and place – a reminder that the city was still something of a frontier town then.

“When it comes to Paris, however, a description of an alarming-sounding dive might well be by Gérard de Nerval, and described by others as well, combining to make a panoramic and credible account. In any case, both cities did ride the crest of modernity – the sudden swelling of fashion and publicity, the speed of railroads and construction – beginning in the 1840s. New York was assiduously studying for its capital-of-the-century exams on the next go-round.”

What gives him hope? “The kids are all right,” says Sante. “Some of them, anyway.”

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: Digging up the backstreets