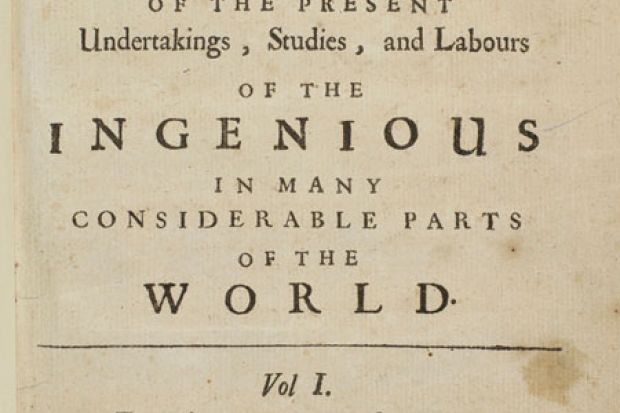

Philosophical Transactions was established in 1665 and, after a period when it was privately run by successive secretaries, formally taken over by the Royal Society in 1752.

That means, said Aileen Fyfe, reader in history at the University of St Andrews, that it has not only “the longest publication history” of any scientific journal but “the archive to back it up” – including, for example, more than 6,000 referees’ reports from the 19th century.

This enables us to trace “the back history of today’s debates on open access, peer review and whether such journals should be profit-making”, she said.

Dr Fyfe is the principal investigator on a research project titled “Publishing the Philosophical Transactions”, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. She is also the lead curator of the society’s new public exhibition, “The Philosophical Transactions: 350 years of publishing at the Royal Society (1665-2015)”, which opened on 2 December.

The material, explained Dr Fyfe, enables us to look “behind the scenes of the process of science journalism and publishing” and to explore “the variety of editorial decisions which eventually led to peer review”. Papers were read at meetings of the Royal Society – by fellows or anyone who could get a fellow to vouch for them – and a secret ballot of a committee then decided whether they should be published.

Under the long presidency of Sir Joseph Banks (1778-1820), concerns were expressed about ways that Banks and his secretaries managed to bypass formal publication processes. In 18, reformers put forward proposals for expert evaluation of papers which, slowly adopted over the next two decades, paved the way for modern peer review.

The Transactions, which always focused on “natural philosophy” or what we would now call science, had published about 8,000 papers by 1887, when it split into separate series for the biological and physical sciences. These included important contributions by everyone from Isaac Newton, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke to Charles Darwin and James Clerk Maxwell.

Yet the same year, 1887, also marked only the third appearance by a woman, Grace C. Franklin, following in the pioneering steps of astronomer Caroline Herschel (1787) and polymath Mary Somerville (1826).