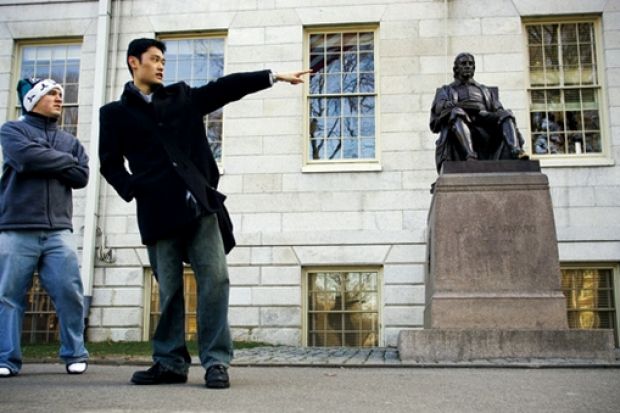

There is little on the Harvard University campus to suggest that this year is different from any other - just a few crimson banners hanging from lamp posts with the word "Celebrate" and a big, block-type "H". Harvard is nothing if not understated.

It would be hard to discern that the US' oldest and most prestigious university - one of its oldest institutions of any kind, for that matter - is this week celebrating the 375th anniversary of the day in October 1636 when it was established by the Great and General Court of the British colony of Massachusetts Bay to "advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity".

In the intervening centuries, Harvard has been parodied, envied, challenged by its Ivy League competitors, and held to impossibly high standards.

But by most measures - notwithstanding the 2011-12 Times Higher Education World University Rankings published last week, which saw it slip to second place behind the more specialist California Institute of Technology - it has remained America's pre-eminent university.

And its president, Drew Gilpin Faust, has decided to use this week's milestone to make sure it stays as robust 25 years from now as it was 25 years ago, when Prince Charles delivered the opening speech at the university's 350th anniversary celebration.

"The way we think about Harvard at 400 is to think about the way the world is going to look different from the way it looked at the time of our 350th," Dr Faust said in an interview with THE.

The university, she said, will add more opportunities for interdisciplinary and experiential learning - clinical experience for prospective lawyers, field-based work for business students, more study abroad - and emphasise technology to help in all those areas, which Dr Faust described in general as "breaking down boundaries".

Next month, Harvard will open an "Innovation Lab" on a new campus it is developing across the Charles River from Cambridge in Boston's Allston section.

The i-lab will incubate cross-disciplinary research involving undergraduates and scholars from the business, law and engineering schools and Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government.

But there are also challenges. The rest of the ambitious Allston campus is mired in delays because of money problems after the university's huge endowment declined by almost 30 per cent as financial markets crashed. A $1 billion (£647 million) high-tech life-sciences complex sits half finished amid other, still-empty construction sites.

Nor do its critics agree that Harvard, with its powerful faculty and long-established customs, really has what Dr Faust calls a "tradition of imaginative change".

Other universities long ago embraced interdisciplinary research and teaching and experiential programmes, for example. In the 19th century, it took one Harvard president 47 years to make significant reforms to the curriculum that other schools had adopted long before.

Dare to be different

Dr Faust's predecessors struggled in vain to end the system by which each of the university's powerful professional schools is run largely autonomously. But she said that Harvard could not rest on its laurels.

"We have very high standards for ourselves and we want to always move in a way that will honour those standards, but that means we have to take risks, make some gestures and institute some programmes that won't necessarily be the most successful ones. Because that's how you find the right paths to the ones that do."

Harvard probably does not have to worry unduly. Its endowment may be down, but it is still $32 billion at a time when other universities are making deep budget cuts.

It has 44 Nobel laureates among its current and former faculty, and 17 million volumes in its libraries. Its alumni are among the world's wealthiest and most powerful people.

But that also gives it special responsibility, said William Deresiewicz, a former Yale University professor and author of the book What the Ivy League Won't Teach You.

"There's no gainsaying the fact that the Harvards of the world are still incredibly important institutions," Dr Deresiewicz said. "That's why it's so important to get it right."