Western universities deserve credit for admitting their historical profits from slavery, according to expert assessments, but have much more work to do on the academic and reparations sides of the ledger.

Major blind spots for higher education, after years of emotional public admissions about past ties to slave labour and profits, include the extensive but little-explored history of medical school experimentation on captives, experts told Times Higher Education’s World Academic Summit.

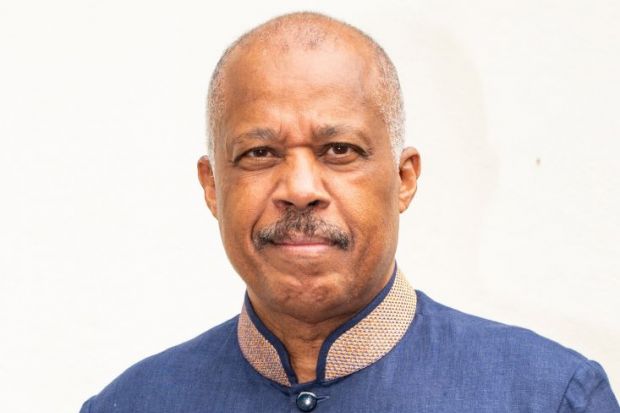

Common practices by US medical schools included sending doctors and their students aboard slave ships and on to plantations to develop their skills, said Sir Hilary Beckles, vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies.

Medical schools and their faculty also owned slaves, even assigning rights to particular body parts while the captives were still alive, Daina Ramey Berry, a professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, told the THE forum.

Many other academic departments helped to legitimise the industry, in ways still needing extensive investigation, said Sir Hilary. They included law schools providing the jurisprudence, economics schools crafting the business strategies, and theology schools endorsing the dehumanisation, he said.

“It was the university sector more than any other that strengthened the ideological and public base of slavery,” said Sir Hilary, a leading advocate for institutions to fully own up to the advantages they have inherited from their past practices.

Universities have taken some major steps in that regard, with dozens acknowledging the slave-derived wealth of their namesakes, major funders, campuses and communities; creating educational programmes to spread that knowledge; and providing educational benefits to slave descendants.

The THE session included Sir Anton Muscatelli, principal of the University of Glasgow, which in 2019 committed £20 million to a research project with the University of West Indies as an act of reparation for its own role in the transatlantic slave trade.

But for higher education overall, that is just a tiny start, Sir Hilary said. Universities throughout the Western world that benefited from slavery need to be ethical leaders on the matter, and listen to outside voices on their true level of accountability, he said.

“Public relations stunts are not adequate,” said Sir Hilary, whose five-campus Jamaica-based institution serves 50,000 students in a 17-nation Caribbean region dominated by descendants of African slaves. “The enormity of this has to be understood.”

The ongoing modern legacy, Sir Hilary said, includes a black Caribbean population that remains “the sickest people in the world”, largely from diabetes that he links to generations brought up in a sugar plantation society.

Part of the needed change, Professor Berry said, includes meaningful adjustments in institutional leadership. One useful model for universities to consider, she said, is Montpelier, the Virginia home of James Madison, the early 19th-century US president, which this summer granted equal governance rights to descendants of people who were enslaved there.

Sir Hilary saw a long process that universities would do well to recognise early and aggressively enable. It took the 19th century to uproot slavery, and the 20th century to achieve civil and human rights, he said. “And now,” he said, “the reparatory justice movement is the 21st-century movement.”