Cheating is “natural and normal” and New Zealand universities must be ready to deal with it, according to an architect of the first comprehensive study of academic wrongdoing by Kiwi undergraduates.

The survey of almost 4,500 students found that deception was rife, with two in three respondents admitting to academic misconduct over the previous year.

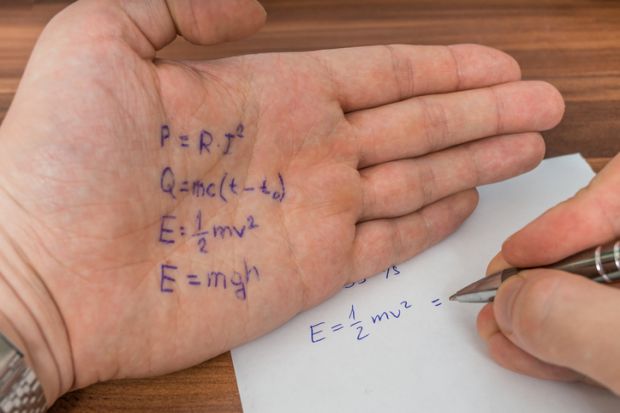

Colluding with other students on ostensibly individual coursework was the most common form of cheating, confessed to by three in 10 respondents. One in five admitted plagiarising a few sentences, falsifying references or downloading course materials without permission.

Fourteen per cent of respondents owned up to plagiarising entire assignments, while 10 per cent admitted fabricating research data. Fifteen per cent said they had used artificial intelligence (AI) tools to produce academic work.

“That certainly has doubled or tripled by now,” said lead author Jason Stephens, an educational psychologist and academic integrity adviser at the University of Auckland. “We collected this data right before the release of ChatGPT. The majority of our cases now are AI.”

Dr Stephens said Covid had also increased opportunities for cheating by forcing more activities online. He condemned remote exams conducted “without any kind of invigilation or proctoring” as a form of “educational or assessment malpractice”.

“We’re…basically just setting students up to cheat, and then doing nothing about it. Not all of them are cheating, but many are. We have little means of detecting it and correcting it. They’re getting away with an unfair advantage that is disadvantaging…honest students.”

Will ChatGPT change our definitions of cheating?

The study has been published in the New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies. The authors say the prevalence of academic misconduct warrants action “at the highest levels of leadership”.

They say New Zealand should emulate its neighbour by adopting the requirements of Australia’s Higher Education Standards Framework. It obliges universities and colleges to implement policies and procedures that guide students about academic integrity, address misconduct or misconduct allegations, mitigate foreseeable risks and prevent recurring breaches.

Dr Stephens said the incidence of self-reported cheating in New Zealand was similar to levels in Australia, Canada, Ireland and the US. Its prevalence should surprise nobody because deception was a “default mechanism” in many lifeforms right down to plants, such as orchids that tricked male wasps into pollinating them by mimicking female wasps’ sex pheromones.

“We have a sense of justice and fairness [but] deception runs deeper and older as an evolutionary mechanism to help us succeed [and] save energy,” Dr Stephens said. “At a conscious level, we sort of justify it. We say, ‘it’s not my fault, it’s the teachers fault’ [or] ‘don’t blame me, I’m just going with the herd’. These are psychological mechanisms that allow us to engage in behaviour that we otherwise would say is wrong.”

He said cheating’s “evolutionary roots” were no excuse for complacency. “We need to expect that…students are going to violate the code on occasion. We need to be vigilant about that and engage in some corrective action when they do.”

The survey found that some forms of cheating were rare. Just 1 per cent admitted to paying others to do their exams or assignments, while 2 per cent had used devices such as smart glasses or watches in exams.

The authors, who come from six of New Zealand’s eight universities, plan to use the survey findings as a baseline for analysing future results.