A British molecular biologist and two US researchers have shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on how cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability.

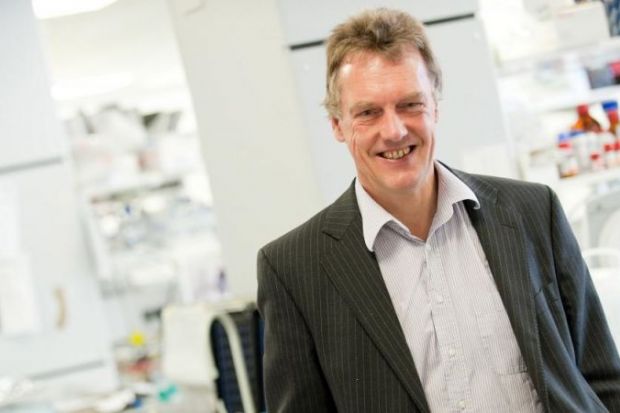

Sir Peter Ratcliffe, director of clinical research at London’s Francis Crick Institute, was awarded the 2019 prize with Harvard Medical School professor William Kaelin and Gregg Semenza, professor of genetic medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

The Nobel committee – which will award a further four prizes this week – said that the trio were responsible for “seminal discoveries [which] revealed the mechanism for one of life’s most essential adaptive processes”. Their work, which had “identified molecular machinery that regulates the activity of genes in response to varying levels of oxygen”, promised to help with the development of “new strategies to fight anaemia, cancer and many other diseases”, the panel said.

Sir Peter’s contribution centred on research conducted at the University of Oxford – where he remains director of the Target Discovery Institute – into oxygen-dependent regulation of the EPO gene.

This research matched similar work done by Professor Semenza, who was studying how the EPO gene was regulated by varying oxygen levels – with both research groups finding that the oxygen-sensing mechanism was present in virtually all tissues, not only in the kidney cells where EPO is normally produced.

At about the same time as they were exploring the regulation of the EPO gene, cancer researcher Professor Kaelin was researching an inherited syndrome, von Hippel-Lindau’s disease (VHL disease) – with Professor Kaelin’s work providing crucial insights into this process.

Oxygen sensing is central to a large number of diseases, the Nobel committee said. For example, patients with chronic renal failure often suffer from severe anaemia due to decreased EPO expression: EPO is essential for controlling the formation of red blood cells. The oxygen-regulated machinery also has an important role in cancer.

Intense ongoing efforts in academic laboratories and pharmaceutical companies are now focused on developing drugs that can interfere with different disease states by either activating or blocking the oxygen-sensing machinery.