Declining applications from India and Nigeria have made international recruitment more challenging than ever this summer, with even some highly selective institutions likely to struggle, according to sector leaders.

While some institutions were still finalising registrations for the new academic year, the number of would-be overseas students submitting UK visa applications was down 17 per cent in the year to the end of August compared with 2023.

“Given the declining real-terms income from domestic tuition and cost pressures within higher education, international student recruitment is more important to UK universities than ever,” Robin Mason, pro vice-chancellor (international) at the University of Birmingham, told Times Higher Education.

“This cycle has been one of the most competitive ever, with significant upward pressure on the cost of acquisition, and all this is compounded by the fact that visa figures indicate a drop this year in international student applications to the UK.”

Professor Mason said the heightened competition for fewer students meant that “the gap between the winners and losers will be larger than ever”, with a handful of universities experiencing significant growth, but more showing declines.

“This is not necessarily driven by mission groups – there are indications that even more selective universities are experiencing falls in international student numbers,” he added.

“It’s going to be a tough year for the sector, and for some institutions in particular.”

The Ucas admissions service recorded 61,110 international undergraduates being accepted by UK universities for 2024-25, a fall of 0.6 per cent on last year.

Although it represents a small portion of the total overseas intake, the data shows some worrying trends. The UK’s two biggest source markets both saw declines, with Chinese enrolment down 1.9 per cent, and India down 3.8 per cent. Nigerian acceptances dropped by 31.4 per cent.

International enrolments are increasingly slanted towards taught postgraduate courses, and these have been heavily impacted by a ban on students bringing dependants with them, which came into force at the start of 2024.

This appears to be putting off students from India and Nigeria in particular, with students from the latter country also affected by the collapse in the value of the naira currency.

In the first six months of 2024 the number of student visas granted to applicants from India was down 28 per cent, with Nigerian awards plummeting by 68 per cent.

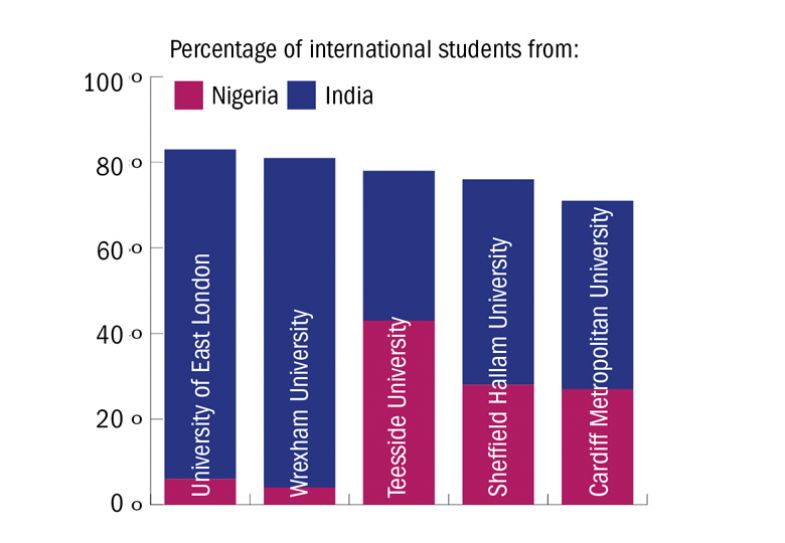

Analysis by THE of Higher Education Statistics Agency figures shows that some institutions have been heavily reliant on these two sectors in recent years: in 2022-23, the most recent year for which data is available, 83 per cent of the overseas intake at the University of East London was from Nigeria or India, with Wrexham, Teesside and Sheffield Hallam universities also drawing more than three-quarters of their international enrolment from these nations.

“This will be a factor for all universities, but especially less selective ones which historically have been the largest recruiters of Indian students,” said Professor Mason.

“And before the dust settles, the recruitment cycle for 2025-26 is already under way, with early indications that it’s not getting any easier,” he added.

George Blake, the policy and networks officer at London Higher, said that while there had been “some recovery in applications since January”, the UK sector could still lose more than £2 billion in international student revenue this year.

“This has already led many in the sector to take difficult decisions around staffing and course closures, with an increasing number of institutions falling into deficit,” he said.