The gap in resources between the UK’s most prestigious universities and the rest of the sector looked set to widen after highly selective institutions shifted further towards lucrative international recruitment in the face of a domestic demographic slump.

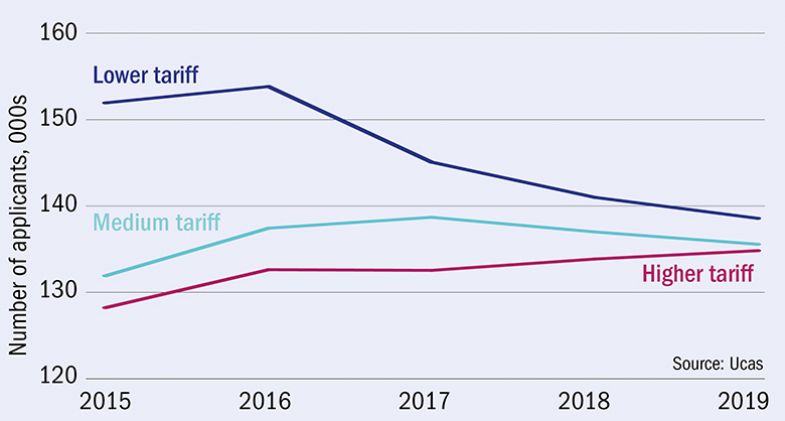

Ucas data showed that the number of applicants placed on UK degree courses at the start of A-level results day fell by 0.7 per cent year-on-year to 408,960. The number of placed applicants has been falling in recent years, largely because of the decline in the number of 18-year-olds in the UK population.

However, while the number of placed applicants at the least selective institutions and medium tariff universities fell by 1.7 per cent and 1 per cent, respectively, the most selective providers increased their intake by 0.7 per cent.

While this was a continuation of an existing trend, this year saw high tariff institutions maximise their international recruitment – and their revenue from higher overseas tuition fees – in a way that less prestigious institutions were unable to replicate.

The number of non-European Union students placed in high tariff universities grew by 10.3 per cent, but remained largely unchanged across the rest of the sector.

In a sign that overseas recruits might be displacing domestic recruits from the UK’s most selective universities, the number of UK-domiciled 18-year-olds placed in high tariff providers was down by 0.7 per cent compared with A-level results day last year, while it held steadier in other institutions.

With Brexit and the possibility of a cut in tuition fees in England as a result of the Augar review looming, recruiting international students has become an important focus for many universities. A recent House of Lords report warned that any reduction to university funding could result in “increasing pressure to recruit more international students to help make up the gap”.

Placed applicants from all domiciles on A-level results day, by tariff group

Overall, the number of international applicants securing places grew by 6.7 per cent, driven by a 32 per cent leap in the number of Chinese students.

Mark Corver, founder of the consultancy firm DataHE and the former head of analysis and research at Ucas, said that the weakening pound was a significant factor.

“If you look at the UK, the quality of the product has stayed the same but it costs a lot less,” he said. “If that didn’t have a positive effect, it would be surprising, and higher tariff universities have the biggest reputations to capitalise on that.”

Amid increasingly competitive recruitment, more Russell Group universities have been entering clearing and some have reduced entry requirements.

However, as the proportion of A-level entries achieving an A or higher fell to 25.5 per cent – its lowest level since 2007 – there were signs that universities felt that they could lower the bar only so far.

The number of students placed at their “firm” choice university was down by 1.2 per cent, and the number ending up at their “insurance” choice was up by 4.6 per cent, suggesting that students who did not get the grades they needed were afforded limited leeway.

UK applications to higher tariff providers were up by 1.3 per cent at this year’s June deadline, but acceptances on results day were down by 1 per cent, suggesting increased selectivity.

Dr Corver said that universities were likely to be conscious of the impact of reducing their entry standards on their performance in certain domestic league tables; while the increasing importance placed on graduate employment data and student satisfaction in exercises such as the teaching excellence framework might also influence selections.

“It’s not just grades; it’s making sure that they recruit people who are going to thrive and be happy in their environment they’re in,” he said.