For the first time, the vast majority of China’s high schoolers will be able to apply to dozens of UK higher education institutions, significantly diversifying their admissions, according to the creators of a university entrance exam.

While China is a top sending country of undergraduate students to the UK, for decades, British universities have been inaccessible to the majority of Chinese pupils.

Currently, Chinese high schoolers taking the international curriculum make up a disproportionate number of applicants from the country seeking to study in the UK. In 2021, they comprised roughly 42 per cent of the 157,000 Chinese students at British universities, according to researcher estimates. But in China, pupils at international schools represent a tiny fraction of all high schoolers.

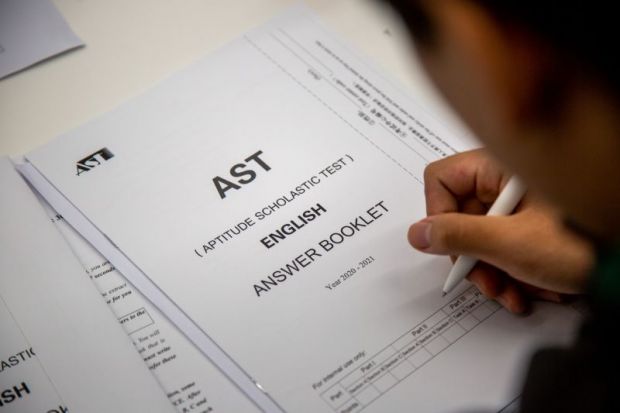

Designers of the Aptitude Scholastic Test (AST) hope that it can broaden access, allowing “99 per cent” of the country’s high schoolers – some 26 million pupils studying the domestic curriculum – to apply to British universities, including extremely competitive top institutions.

Twenty-three universities in the UK and Ireland have started accepting the test since its launch in 2008, with roughly half of them joining since the start of 2022. Recent adopters include the University of Liverpool and University College Cork, both of which signed on last month.

“There is a strong case to be made for the AST in terms of diversifying the student cohort and widening access,” said Jacob Lotinga, UK and Ireland director at Ambright Education Group, the company that developed the test along with University of Cambridge academics.

In 2021, just over 560 students took the test – a comparative drop in the ocean – but he said the company expects their number to rise “significantly” this year.

The test costs ¥800 (£95) per subject, although students can apply for financial aid. It is offered in 50 test centres around China. Crucially, it doesn’t require students to get specific coaching, something that’s true of international curriculum tests, said Mr Lotinga.

David Cardwell, a professor of engineering at the University of Cambridge who helped develop the AST test and who oversees its physics test, said it has helped reach high-scoring students previously unable to apply to his institution.

“We have 1,700 students who are entirely appropriate to go to Cambridge; the problem is how to evaluate their academic potential – this is where we started working with Ambright,” he said.

He said that the gaokao, a test widely used for undergraduate admissions into Chinese universities, isn’t accepted by many Western institutions. Among other issues, it isn’t purely based on academic scores, sometimes including marks for sports achievement or other extracurricular activities.

“I’ve even seen headmasters’ points awarded and credits for non-academic activity. I’m not saying that’s wrong, but [it is] not suitable [for] the level playing field at Cambridge,” said Professor Cardwell.

The AST is based on scores in standard academic subjects including English, maths and physics. While it is “loosely based” on what students in mainland China study in their domestic curriculum, it is in English and standardised, according to Ambright.

Alex Ingold, undergraduate admissions manager at the London School of Economics, which this year began accepting the AST, said that increasing student diversity was a “main driver” in LSE using the test.

“Many institutions do not accept gaokao for direct entry to undergraduate programmes; that is a major barrier,” he said.

While Mr Ingold said it’s “too early to tell” about the test’s impact on LSE’s admissions, he confirmed that currently, students taking the International Baccalaureate curriculum or A levels make up the majority of Chinese students enrolled at the university – something he would like to see change.

“We hope it will allow us to widen diversity in our Chinese student cohort, allowing us to identify the best and brightest students taking the gaokao with a view to making them offers and ultimately welcoming them to LSE,” he said.