“Universities must…” The Office for Students often wields this phrase in public statements. The English sector’s new regulator has warned that “universities must ensure they…support students’ mental health and well-being”, that “universities must improve their diversity levels – or we will use our powers to penalise them”, that “universities must eliminate equality gaps”, and that “universities must get to grips with spiralling grade inflation”.

One vice-chancellor said he believed that the OfS’ reliance on the phrase revealed a failure to grasp that university autonomy is integral to the world-leading status of the UK higher education sector, and highlighted a tendency to rely on “threats” since the move from funding council to “fining council”.

Others in the sector are more of the opinion that the OfS has been handed a near-impossible job by the government’s requirement for it to regulate in the student interest while also protecting university autonomy – but they worry that an interventionist approach breaks with many decades of light-touch regulation that has seen British higher education thrive.

The year since the OfS was established offers a chance to take stock of its impact. Given present financial problems at some institutions, it is not impossible to imagine the OfS being faced with an institutional failure in the next 18 months – so the regulator’s nature might prove vital.

There is also another key question: is the abolition of the OfS already a genuine possibility?

The OfS, led by chair Sir Michael Barber and chief executive Nicola Dandridge, has “not established itself as a body which commands respect”, said David Green, vice-chancellor of the University of Worcester. “And the reason for that – despite the fact there are many talented and experienced colleagues who transferred from the [predecessor] funding council to the OfS – is because of the leadership…and the legislative basis on which it was established.”

The OfS “came into force” on 1 January 2018 and began full operations on 1 April, succeeding the Higher Education Funding Council for England, whose powers were based around the allocation of grants. The OfS was established by the Conservative government’s Higher Education and Research Act, reflecting a belief in Westminster that the switch to a funding system based largely on students’ tuition fees required a new regulator with new powers.

The OfS has powers to fine institutions or even, in the most extreme cases, to remove them from its register of providers – which would prevent students at an institution from accessing public loans. In a broader philosophical shift, Jo Johnson, the former universities minister behind the act, wanted the OfS to enforce the market rights of students as consumers and to promote competition between providers.

Hefce looked at the financial health of the sector overall – and offered behind-the-scenes guidance to nudge matters in the direction it wanted, both at sector level and at individual institutions.

By contrast, argued Professor Green, the OfS leadership’s “modus operandi is to threaten, not to reason”.

He added: “Students will flourish when universities flourish; they will get into trouble when their university gets into trouble. The OfS has no brief for trying to help institutions flourish and succeed. Its only brief is to fine, punish and threaten.”

The OfS has so far announced fines for two institutions, the University of Hertfordshire and Writtle University College, over “major access agreement breaches”.

One major challenge the OfS has been handed by the government legislation is the Herculean, ongoing task of assessing all these institutions for inclusion (or otherwise) on the register of providers.

There are also concerns about the OfS’ staff numbers, both in terms of cost (universities will pay the regulator’s running costs through their registration fees as of 1 August) and, potentially, increased power.

An OfS spokesman said that the organisation’s agreed structure “provides for 398 posts”.

In March 2012, Hefce had a staff headcount of 255, while the Office for Fair Access (also now subsumed within the OfS) had 13.3 full-time equivalent staff, though the totals when the organisations ceased operations were 356 and 29, respectively.

But, while Hefce had responsibility for research funding, the OfS does not (Hefce’s responsibilities in this area have been passed to another new organisation, Research England).

Shortly before Christmas, the OfS was advertising jobs in 13 different roles. These included competition and registration manager posts in a £69,000-£72,000 salary band and a principal analyst on gateways in a £57,000-£60,000 salary band – all based at the OfS’ Bristol office.

Gordon McKenzie, chief executive of GuildHE and a former senior civil servant responsible for higher education, said that the OfS “must demonstrate value for money itself as well as demanding it from higher education institutions”.

“Getting institutions registered is a huge task, and it’s right that the OfS has the resources to do it effectively. But once it’s done, costs should come down – longer term, a light-touch regulator with no policy or research funding responsibility should cost much less than Hefce,” Mr McKenzie said.

Some warn that there is, in the UK nations, a perception that the OfS is guilty of English imperialism and has taken a unilateral approach to UK-wide sector issues.

During work on revising the UK Quality Code last year, the Universities UK president and other senior figures wrote to Sir Michael to warn that the OfS was not treating the nations with “respect”.

Another area of concern in the sector is the OfS’ attitude to potential institutional failures. “We will not bail out universities or other course providers in financial difficulty,” Sir Michael said in November. He chose a Daily Telegraph opinion article to issue that message to the sector – the newspaper’s headline referred to “bad universities” – along with a Today programme interview on BBC Radio 4. The OfS has certainly sought more media coverage than Hefce.

Professor Green said of the institutional failure stance: “How it could possibly be in the interests of students at a university for [the] university to go into some form of disorderly collapse, I’m afraid escapes me. But that is being anticipated by the OfS and, it would seem to me, politically almost welcomed – ‘bring it on’.”

Given that a university may be the biggest employer in its town or city and the most vital economic force in its region, the OfS’ solely market-focused approach to potential market failure risks looking outmoded in the post-Brexit political debate, when regional inequality is belatedly being addressed. In higher education, a report for the Welsh government has recommended that part of universities’ funding should be tied to their civic role, and one of the report’s authors, John Goddard, has predicted that England’s marketisation “crisis” will force the government to shift policy focus towards “the well-being of the system overall” and universities’ responsibilities to their local communities.

When it comes to the uncertain future faced by some institutions, perhaps the OfS itself should be counted among them.

“The OfS is probably not long for this world as a body,” said Professor Green, highlighting the Office for National Statistics’ report on the account treatment of student loans, which will dramatically increase the amount of university funding classed as direct government spending – to some extent reversing the funding changes that led to the creation of the new regulator.

He added that “a new parliament is bound to bring forward a different funding system for universities” and that any such change would require “some form of funding council rather than the fining council, which is what the OfS has turned itself into”.

Labour’s plans to abolish tuition fees and fund universities wholly through direct public spending would also, presumably, require a return to some form of funding council.

Meanwhile, the Association of Colleges has urged the government’s review of post-18 education to create “a new regulator operating with three parallel arms covering schools, colleges and universities”.

Ms Dandridge said that the OfS’ “role and duties are clearly set out in legislation and our own regulatory framework. We respect institutional autonomy, and have regard to it when making our decisions, balancing it with our other duties.”

She added: “Of course, a new regulatory regime is not going to be entirely comfortable for all universities and colleges. Nor should it be. We have worked constructively and respectfully with providers, and will continue to do so.

“But this does not mean compromising on our regulatory responsibilities. Instead, we will continue to regulate in a way which helps ensure that all students, from all backgrounds, have a fulfilling experience of higher education which enriches their lives and careers.”

Perhaps one of the key points is that the OfS has come into existence just as politicians’ and policymakers’ faith in universities has collapsed, in the wake of the £9,000 fee settlement. In the absence of the Hefce “buffer”, universities now feel the chill of government disfavour more keenly.

后记

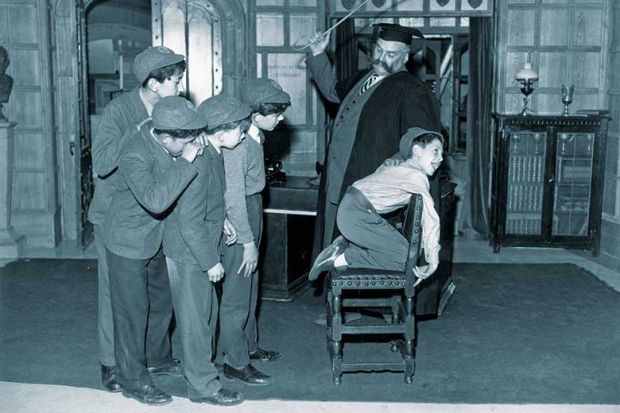

Print headline: ‘Quick with the rod’, but is the OfS up to the job?