The continuing dominance of the traditional full-time undergraduate degree risks undermining the objectives of the government’s planned lifelong loans in England, the Open University’s vice-chancellor has warned.

Funding being made available as part of the government’s lifelong learning entitlement (LLE) will need to be significantly expanded or will be eaten up by costly residential programmes, Tim Blackman writes in a foreword to a new Higher Education Policy Institute (Hepi) report, published on 11 May.

The LLE will provide students with the equivalent of four years’ worth of fee funding for higher education (currently £37,000) and aims to provide more flexibility than the current student finance system so that, for example, learners could use the funding to take individual modules as and when they wish over the course of their working lives.

Ministers say this will better allow the country to address skills gaps and help individuals train in a way that equips them to deal with the changing world of work.

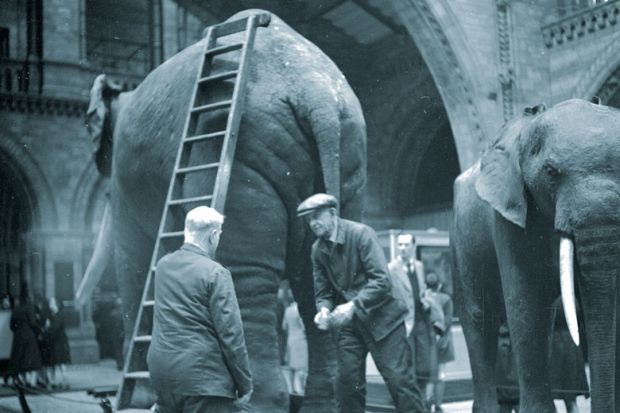

“There is, though, an elephant in the room, which is the full-time undergraduate degree, especially the costly residential versions that dominate provision by the most academically selective and therefore most socially exclusive universities,” Professor Blackman writes.

“The LLE will not work in spreading the benefits of higher education over a working lifetime as well as across a wider social spectrum if this type of provision still consumes such a large share of student support, with students who choose this option using up almost all their LLE in one qualification that, in today’s world, dates rapidly.”

One solution, according to the head of the country’s largest university, would be to expand funding support significantly beyond current levels because “the present system is going to struggle financially just to keep up with growth in the current pattern of participation. There are difficult choices ahead about how to divide up the cake.”

The report’s author, Rose Stephenson, Hepi’s new director of policy and advocacy, said that while there would continue to be great demand for traditional undergraduate degrees, to be “transformative”, the LLE must also meet the demands of those who do not engage with universities as full-time, in-person students.

The government’s lifelong learning plans further risk “perpetuating the inequities of the current system”, Professor Blackman writes, by not providing access to maintenance support for distance-learning students.

This exclusion has not been properly explained by policymakers, Ms Stephenson said, and “risks holding higher education out of reach from the learners the government would most like to target”.

Another crucial element of the LLE that still needs to be outlined concerns how credit transfers are handled, Ms Stephenson writes in the report.

Learners will need to be able to know if they can take modules at multiple providers, and what rules will be involved in doing so, such as whether they could study a variety of unconnected modules from different subject areas – or several very similar modules – and still be awarded a full degree.

“There is an uncomfortable question here for the higher education sector,” Ms Stephenson writes. “Are all modules and all higher education institutions considered equal? Would a module from a less selective university be transferable to a more selective university?”

Regulation of the sector would also need to change to better open up the opportunities presented by the policy, she adds.