The number of students accepting places at UK universities through clearing is marginally up on 2023 so far, but institutions outside the top tier are finding the going tough, Ucas figures suggest.

Data released by the admissions service showed that 42,020 students have accepted places in the four days since A-level results day, up 0.4 per cent year-on-year.

The increase has been driven by a 17.5 per cent increase in the number of students winning places after going directly into clearing, which have hit 8,000, in line with comments made by Ucas chief executive Jo Saxton that more students have been declining firm offers to enter clearing to choose another course.

A total of 461,800 students have now been accepted, up 1.2 per cent compared with 2023, despite a 1.6 per cent fall in applications, supporting the picture emerging of universities moving as swiftly as possibly to confirm their intake, mindful that this recruitment cycle is likely to prove critical as financial pressures on the UK sector increase.

But the gap in the fortunes of the most- and least-selective universities has widened in recent days.

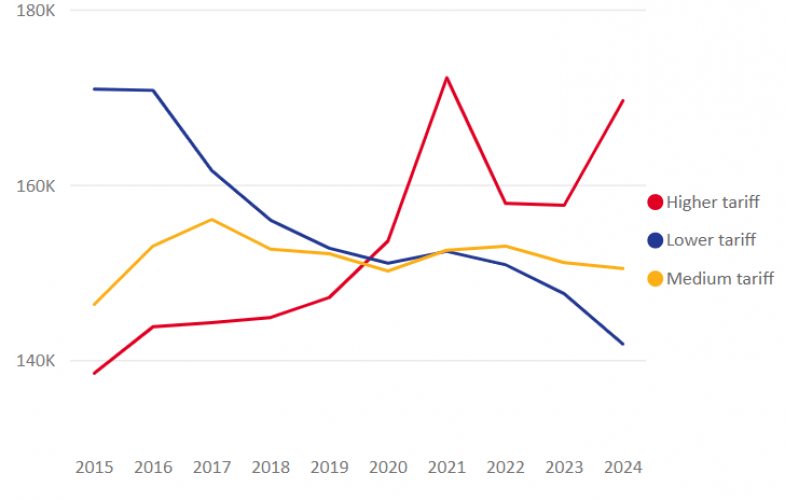

Four days on from results day, 169,570 students had accepted places at high-tariff universities, up 7.6 per cent year-on-year. In contrast, low-tariff institutions’ intake of 141,800 is down 3.9 per cent. Medium-tariff universities have confirmed 150,430 students, down 0.4 per cent.

On results day, high-tariff universities’ expansion stood at 2.6 per cent, with the low-tariff shrinkage at 1.8 per cent – figures that prompted one sector leader to tell Times Higher Education that some institutions could be facing “really significant difficulties”.

Number of accepted applicants, four days after results day

There are now 136,370 applicants still free to be placed via clearing, down 9.9 per cent at the same point last year.

Mike Nicholson, director of recruitment, admissions and participation at the University of Cambridge said he was “not surprised” at the figures, adding that the increase in students securing their first-choice option meant that fewer were looking for alternative places.

And while the figures could indicate bad news for low-tariff universities amid ongoing financial hardships, Mr Nicholson said there was still time for the figures to improve for such institutions.

“Day one tends to be the only day where opportunities are available at high-tariff universities, so this is likely to be the high point for them,” he said, noting that the University of Bath had 13 courses in clearing at 8am on results day, but had filled all its places for domestic enquiries by the close of play.

“Over the last two admissions cycles there has been a steady increase in applicants holding off from making an application through Ucas until they have their results, and as they are more likely to be mature students – this is likely to benefit the lower-tariff universities. These applicants will enter the system over several days,” Mr Nicholson said.

“Clearing runs for several weeks, so whilst the political and media focus tends to be on results day in mid-August, we won’t have a sense of the full picture until late September.”