A “famine or feast” admissions round that could drive some universities out of business has reignited calls for student numbers controls (SNCs) to be brought back in England, with the new Labour government coming under pressure to act from both sides of the political spectrum.

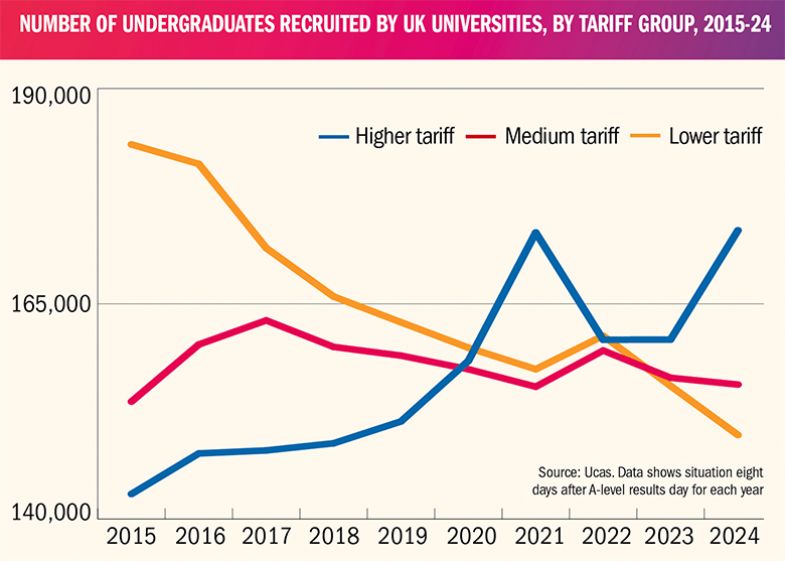

Faced with dwindling international enrolments, higher-tariff institutions have moved heavily into the domestic market, hoovering up 18-year-old applicants at levels last seen in the Covid-affected years, when teacher-assessed grades swelled undergraduate numbers.

The Russell Group – which represents many of the higher-tariff universities – has insisted that its members are well prepared for the increased demand, but critics fear a return of large class sizes and accommodation shortages, as was the case during the pandemic.

The knock-on impact on lower-tariff universities was also raising concerns, with missed recruitment targets all the more serious because of the financial crisis engulfing the sector.

Balihar Sanghera, head of the School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research at the University of Kent – one of the institutions squeezed hardest by higher-tariff expansion – said there was “palpable” anger and frustration at the situation. “There is a sense this cannot go on,” he added.

Kent has already been forced to take drastic action to deal with a £12 million deficit caused in part by under-recruitment, and Dr Sanghera said that rather than expecting individual universities to sort out the issues via restructuring, a “collective, structural solution” was needed.

He said reintroducing recruitment caps similar to those abolished by the Conservative government in 2015 should be part of a package of interventions to bring stability back into the system.

“Student number controls are not a panacea,” he said. “They will not solve everything. But this year, they would have made a significant impact in preventing the Russell Group from taking a lion’s share at the expense of causing other universities to go the wall, pushing them into deficit or further into deficit.

“When the overall numbers aren’t growing by much, if some universities are taking more students, it is at the expense of others; if there are winners, there will have to be losers. It is a thrive or perish ideology.”

Reintroducing student number caps has been repeatedly proposed ever since their abolition, most recently by the former Conservative government, which sought to restrict the number of students entering “poor quality” courses, in a move opposed by Labour at the time.

Nick Hillman, who, as former special adviser in the Department for Education, was one of the architects of the uncapped system, conceded that the latest developments would reignite the debate.

“They [SNCs] are the beast that never dies,” said Mr Hillman, now director of the Higher Education Policy Institute. “I do recognise that some advocates of student number caps believe they are acting in the interests of students by trying to reduce the amount of flux in the system, though others seem more motivated by staff concerns than student concerns.

“But the main problem is that bean counters in Whitehall like caps because they save money, whereas people who care about education should not, in my view, be campaigning for there to be higher barriers to education or less education overall.”

But this view was being countered by an unlikely coalition of voices. Jo Grady, general secretary of the University and College Union, which backs number caps, said universities being forced to compete with each other so that some have to house students miles away while others make drastic cuts was “not good for staff and not good for students”.

She said institutions needed to move away from focusing on short-term student recruitment cycles and plan for the long term.

“But for this to happen, Labour needs to put forward proposals for sustainably managing the numbers of students at universities across the sector and back this with increases in public funding,” Dr Grady said.

Iain Mansfield, former special adviser to Conservative universities ministers and now head of education at the right-wing thinktank Policy Exchange, said the “famine and feast of this year’s admissions cycle shows that volatility is as much a threat to university financial sustainability as the absolute unit of resource”.

He questioned whether quality was being maintained at institutions that have rapidly expanded, “or are academic standards and seminar sizes being quietly relaxed?”

“For a government determined to reduce the risk of an unplanned provider exit, restoring the system of student number controls that operated throughout the New Labour years would bring valuable stability to the system,” Mr Mansfield said.

A Russell Group spokesperson said its universities “continue to only accept students who have the capability to succeed on their chosen course, and we are committed to delivering a high-quality education and student experience for everyone”.

后记

Print headline: Calls for student number controls as elite intake swells