England’s universities take plenty of flak these days – but being linked, albeit indirectly, with organised crime was particularly explosive.

In a political context where the value of expanded higher education is continually under question from Conservative MPs, ministers and some newspapers, the sector landed itself with another problem last month: an investigation by the UK’s public spending watchdog into franchised higher education provision.

The National Audit Office investigation came partly in response to the Student Loans Company detecting fraud in franchised provision, in which universities subcontract the delivery of their courses to colleges. Such franchised provision accounted for 53 per cent of the value of the total £4.1 million in fraud detected by the SLC in 2022-23, with one case of fraud at a franchised provider “potentially associated with organised crime”, says the NAO report. Loans provided by the SLC come from government funds, hence the NAO’s interest.

The investigation also responded to a 2023 article by The New York Times on the Slough-based, for-profit Oxford Business College – offering degrees from three universities under franchising – which the newspaper said was making millions via public loans while recruiting students who struggled to speak English. The institution insisted that it has robust admission requirements.

Franchising is an issue that will run and run. In a hearing on 26 February, MPs on the Public Accounts Committee, one of the highest-profile stages in Westminster politics, will examine the NAO’s findings.

And even before the NAO report, the Department for Education had said it would explore the possibility of introducing “additional controls” on franchising.

The NAO report raises questions about the potential risks from substandard franchising for universities; about a failure to learn from previous scandals over for-profit providers; about the potential loss of benefits from franchising if universities withdraw under greater scrutiny; and about whether the political and policy context has been a factor fuelling problems.

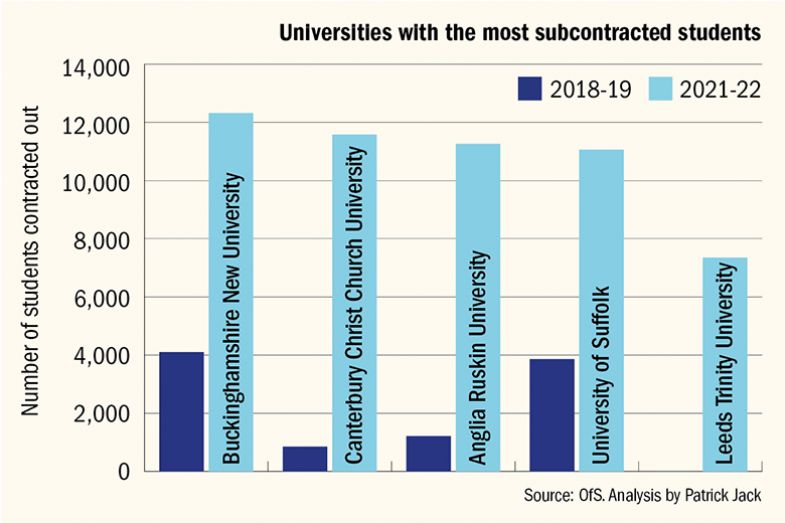

A small number of universities – known as “lead providers” when they subcontract courses – have opted for rapid growth in their numbers of franchised students. Analysis by Times Higher Education of Office for Students data shows four institutions with more than 10,000 students on courses subcontracted to other providers. Buckinghamshire New University, in top spot (one of the universities to partner with Oxford Business College), had 12,320 franchised students in 2021-22 – up from 4,100 three years earlier. Leeds Trinity University, in fifth spot, had 7,350 franchised students – up from none three years earlier, according to the OfS data.

Sector-wide, the number of students enrolled at franchised providers more than doubled, from 50,440 in 2018-19 to 108,600 in 2021-22, amounting to 4.7 per cent of the total student population, the NAO says. But just eight lead providers were responsible for 91 per cent of this growth.

The core of the problems identified by the NAO lies in the fact that, while lead providers have to be registered with the OfS, giving the institution’s students access to public student loans and meaning it comes under OfS regulatory oversight including on quality conditions, franchised providers do not need to register. “In 2021-22, 229 (65 per cent) of the 355 franchised providers were not registered,” says the NAO, warning of a regulatory gap.

The NAO report raised “serious implications from a legal perspective” for universities, said Smita Jamdar, a partner and head of education at the law firm Shakespeare Martineau.

The OfS’ regulatory framework spells things out: “Lead providers subcontracting all or part of a course to a delivery provider retain responsibility for the students on those courses and the quality and standards of provision.”

However, says the NAO, “lead providers benefit financially from increasing student numbers” – it cites the OfS as saying that some lead providers retained up to 30 per cent of tuition fee payments under franchise deals – “and have few incentives to detect abuse of the student loans system”.

This regulatory gap is one in which abuse is taking root, the public spending watchdog argues.

Ms Jamdar said that, given the OfS’ regulatory requirements around franchising, universities entering into partnerships must conduct due diligence on the partner; carefully prepare contracts; ensure information flows are in place once partnerships are up and running to “check what the partner is actually doing”; and prepare “provisions to take action” if there are quality or other problems.

The “direction of travel” on franchising was clear even before the NAO report, added Ms Jamdar. “We’ve been advising institutions that partnerships are becoming increasingly risky from a regulatory perspective,” she continued. “If things go wrong, you [universities] are the ones being investigated and your [OfS] registration is potentially the one that’s under scrutiny.”

If universities were to withdraw from franchising, what would be the downside?

“At the heart of franchised provision for universities is a relationship that brings both financial stability and opportunities to extend widening participation by reaching under-represented populations in higher education,” said Nick Braisby, the Bucks New vice-chancellor.

Indeed, that point is made by the NAO. “DfE considers that franchising helps widen access to higher education,” says its report. “In 2021-22, 57,470 out of 97,000 (59 per cent) students from England studying at franchised providers were from neighbourhoods classed as high deprivation, compared with 40 per cent of students at all providers.”

But what kinds of colleges are providing the franchised provision?

The NAO says that, of the 108,600 students on franchised courses in 2021-22, 58 per cent were “enrolled on business and management-related courses”.

The website WonkHE looked at data showing the OfS-registered for-profit colleges that were faring worst, for franchised provision, on the regulator’s B3 student outcomes measures on continuation, completion and progression.

Several of the London for-profit colleges on that list also featured on a list of for-profit colleges that had their designation for student loan funding suspended by what was then the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills in 2013. That came as the Conservative-led coalition government attempted to wrestle back control after its attempts to drive market competition led to large numbers of small for-profit colleges gaining access to public loan funding for sub-degree programmes and massively increasing recruitment.

But the NAO does not draw a distinction between different kinds of franchise partners. For some universities, partnerships are not with for-profit colleges, but with public further education colleges.

The University of Worcester had 780 students on franchised courses in 2021-22, according to the OfS data.

Worcester’s partnership work was “very valuable work from a widening participation perspective and is part of…our commitment to widen participation in non-university towns and rural areas”, said its vice-chancellor, David Green. For example, Worcester is currently working with Dudley College of Technology, a further and higher education college, to develop education for the health professions in the Black Country.

“Systematic fraud by private for-profit providers is clearly a significant issue,” continued Professor Green. “It is not that there can’t be fraud in not-for-profits,” he said. “But it is relatively rare, whereas the experience of for-profits is patchy at best.”

Meanwhile, Alex Proudfoot, chief executive of Independent Higher Education, whose membership of 77 institutions includes new providers, said he was concerned by references to organised crime and fraud in the NAO report, but added: “I don’t think that sort of element is particularly exclusive to franchised provision…That could happen at any institution without necessary controls in place.

“We wouldn’t want the baby thrown out with the bathwater in terms of partnerships and franchising specifically.”

Mr Proudfoot said franchising’s appeal to new providers stemmed from the fact that it “allows them to focus on teaching and what they are good at”, and that the OfS process for new providers “takes far too long”. “If there was a streamlined, efficient, proportionate process that new providers could access and be confident about accessing it in a time frame their investors are comfortable with, then most of them would do it,” he added.

While some universities should think more carefully about the partners that they choose, many would argue, perhaps government policy has been a factor here.

Ms Jamdar said some universities might have entered franchise partnerships a few years ago when the “political mood” was in favour of opening the market and many new providers were looking for university partners. “Now the mood music has gone away from that, towards much more scrutiny around who’s coming into the market,” she added. “[Universities] will have entered into partnerships on one mood music and now they are facing another one where they have got to look again at their partnerships…[and] whether they should continue with them.”

In terms of the funding context, perhaps there are parallels between franchising and overseas student income. Energy and staff costs have risen fast under high inflation as teaching funding sees big real-terms cuts under the government’s fee cap freeze, meaning universities have inevitably looked to increase the only alternative income streams they have.

But the risk was that “the money ends up doing the talking when the real benefits of franchising arrangements, when they work well”, were in franchisees being able to “do things differently and reach different students”, said Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute. “So I would hate to see franchise arrangements stop, but we do always need to shine a spotlight on the arrangements to make sure they are delivering for the people who matter most – the students – and have not got out of kilter.”

The NAO calls for the DfE and OfS to work more closely together and with the SLC on tackling fraud, and in stressing to universities that they “bear direct responsibility for the governance and management practices of franchised providers”. Here, Universities UK might have an important role to play in setting guidelines that raise universities’ standards on partnerships. In particular, it seems bemusing that some of the same names involved in the last scandal over for-profit colleges maximising their access to public funding via questionable recruitment practices are recurring in similar circumstances.

At a time when universities are already under a number of painful political pressure points, self-inflicted wounds are to be avoided.