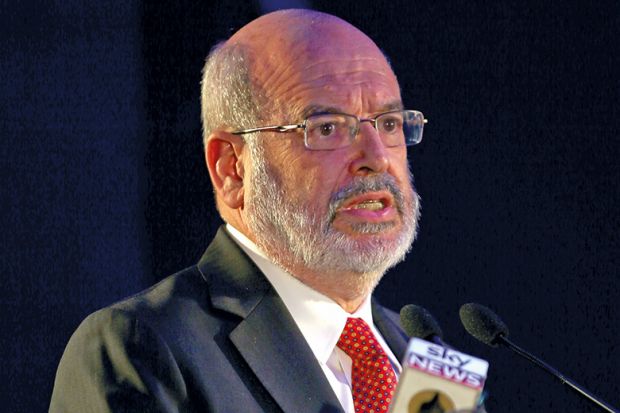

“Dr Google” is a bigger threat to evidence-based policymaking than the anti-science polemics of populist politicians, according to the incoming head of the International Science Council.

Paediatrician turned science diplomat Sir Peter Gluckman said that science faced a challenge from Donald Trump’s questioning of the consensus on climate change, and former UK education secretary Michael Gove’s pronouncement that Britons had grown tired of experts.

But Sir Peter said that such attitudes were symptoms of a broader problem spawned by the internet. “Everybody now has access to information. Whether it’s reliable or unreliable is beside the point,” he told Times Higher Education.

“That’s led many to think they no longer need experts. There’s a hubris [in] that people think ‘Mr Google’ or ‘Mr Wikipedia’ are enough. That’s not the case. Data needs analysis and interpretation.”

Sir Peter said that science needed to engage with climate change deniers and the “anti-vax” movement. “There’s no point screaming at these people and saying they’re idiots. We need to understand what leads people to particular positions, and recognise that science has a challenge here.”

Sir Peter added: “It doesn’t matter how much we plead to people to have a measles vaccine. The anti-vax movement continues to believe that there’s no need to do so. It doesn’t matter how much the evidence is robust around climate change; there will be people who for whatever reason don’t want to accept climate change is a challenge that must be addressed. There are various reasons why that happens. We need to understand that. It’s not just a matter of better science communication. That’s a trivial way of putting it.”

Sir Peter’s nine-year spell as New Zealand’s chief science adviser ended last year, shortly before he was named president-elect of the ISC. His selection as chief-in-waiting – to be consummated in 2021, when inaugural president Daya Reddy’s term concludes – coincided with the global body’s fusion from two separate bodies, the International Council of Scientific Unions and the International Social Science Council.

The merger “brings the full range of knowledge disciplines into one forum” and will “allow commonality of language to emerge”, Sir Peter said. It also marked a greater focus on the “interplay” between science and policy.

“There needs to be a far more pragmatic way of dealing with issues where evidence is needed to make better decisions for the planet and its citizens. Scientific evidence is one of the inputs into a much more complex equation. Ultimately, at least in a liberal democracy, values such as public opinion, public priorities and electoral context come into play,” Sir Peter said.

Sir Peter said that governments would always do things that “frankly are sometimes stupid. But my experience is [that] when you explain what science can do, acknowledge what science cannot do and recognise the many other domains in a policy community, most governments are more willing to have science at the table. That’s what this is all about.”

Spearheading the effort will be the International Network for Government Science Advice, which Sir Peter helped establish five years ago when he convened the world’s first global meeting of high-level science advisers.

He said that he expected some of the group’s current work to be presented to the United Nations this year, including attempts to give the Sustainable Development Goals more policy clout.

The ISC has also appointed Flavia Schlegel, a former assistant director general of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, as its special envoy for science in global policy. “It’s not a matter of just turning up and knocking on the doors of international agencies,” Sir Peter said. “We will have an ongoing interaction with them.”

Sir Peter said that science needed to recognise its limitations as well as its strengths. “Science can explain complex systems. When there are many unknowns, we can reduce the level of uncertainty. We can say where it is desirable to get a different outcome and what options are likely to achieve it, and analyse the pluses and minuses of any action,” he said.

“Then we leave it for the policy community to choose between the options. What we cannot do – and what is the wrong thing to do – is to say that because A causes B, therefore government must do C. That is where the hubris of science has been a problem.”

后记

Print headline: Engage with climate deniers and anti-vaxxers, says science diplomat