When he was a boy, Brian Duffy stole from bombed-out houses (The Man Who Shot the 60s, BBC Four, Monday 19 April, 10.30pm). "I really enjoyed the war," he said. Children can be so unfeeling. "I was a thug." A history that must have helped when getting the Kray twins to relax in front of the camera. Brian was rescued from this idyllic existence by being taken to the opera, art galleries and the ballet. It transformed him. All those who despise the arts, please take note.

Brian swapped his knuckledusters for a paintbrush. But not being the genius his fellow students imagined themselves to be, he "knocked that one on the head", a fitting expression given what we had already learned about him.

People can surprise you, though. Brian's next venture was dressmaking. "There were a lot of pretty girls," he explained. For a moment, it seemed as if he might smile. But the moment passed. Brian spoke about his life with all the warmth and enthusiasm of someone telling the time. Which, in a way, he was.

Just as he was about to take a job in Paris, his wife, June, fell pregnant. "Good gracious," said Brian. He needed money quickly. What about photography? It "was a darn sight easier than drawing". And, no doubt, less risky than demanding money with menaces. You wouldn't want to trespass on Ron and Reggie's ground.

And so Duffy, as he became known, joined David Bailey and Terence Donovan to form "the terrible trio". They were working-class boys whose cheekiness sent a frisson down the spine of middle-class society. They didn't tug their forelocks, they flicked their quiffs. And in the words of Robin Muir, photographic historian, they brought "a sense of reality" to magazine pictures. Robin's beard lent momentary gravitas to that statement before it collapsed under the weight of its own absurdity. Fashion photographers do not portray reality, they promote an ideal.

Can photography be art? A question that has boosted the sale of cappuccinos and produced an equal amount of intellectual froth. Anyone can take a picture, but it takes an artist to make an image. One of Brian's first photographs was of a snail perched atop an eyeball. Not pretty. And not particularly original. Luis Bunuel went much further in Un Chien Andalou (1929). A man drawing a razor across a woman's eye, what's that all about? An act of sadism? A symbol of how we must rid ourselves of normal vision so that we can see anew?

Duffy resisted all interrogations of this sort. "Artists", he remarked, "are always talking drivel." Which makes you wonder why he agreed to be filmed. Ah, there was his son, Chris, on hand to explain.

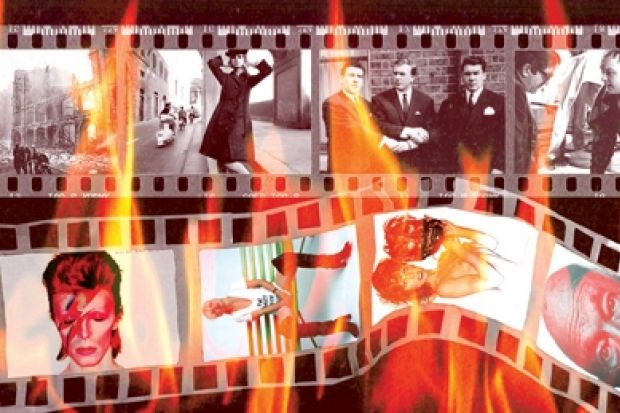

Back in 1979, Duffy tossed aside his camera and burned all his photos. Something to do with the incompatibility of art and ordering toilet rolls. David Bailey tried to step between the dragon and his wrath but to no avail. Luckily one box escaped the flames. It was the discovery of that which inspired Chris to get his father working again and to mount the first exhibition of his pictures.

Joanna Lumley recalled being photographed by Duffy in the 1960s. There were lots of records and wine bottles. "He would make you say 'Thursday' slowly so that your mouth went a funny shape." A shot of Joanna cradling her baby son, James, filled the screen. Duffy did a new picture of them. "There's a pleasure in making someone look beautiful," he said. Most would say Ms Lumley gives him a head start.

She was one of the many celebrities snapped by Duffy over the years. He missed his appointment with Millicent Martin, though, having got severely drunk one lunchtime. Duffy pondered his portraits. "People change when you look at them through a lens. The moment of the photo is interesting, but not the moment after." It was the nearest we got to a philosophy.

More typical was his remark, "Sod the aesthetic, think of the money." This applied particularly to his most famous image, the cover of David Bowie's Aladdin Sane. It showed the star with stiff red hair, lightning down his face and a teardrop on his collarbone.

There was a lot of music. But it wasn't all evocative of the era. The Kinks, yes. But Louis Armstrong? The tracks served as fillers. And perhaps as a reminder that neither songs nor snapshots define a period, they caricature it.

The most arresting sight was Molly Parkin. Dressed in an outfit straight out of the Dr Who wardrobe department, she echoed the view that Duffy was "a bit of a bastard". Even David Bailey, resplendent in a pink shirt with white flowers, conceded that his best friend was "difficult". But aren't all artists?