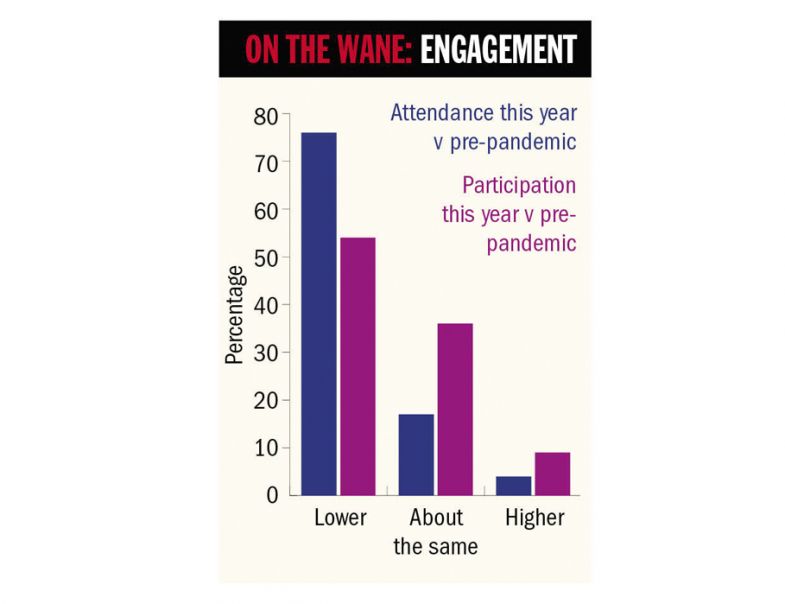

Student attendance and in-class participation remain at a far lower level compared with before the pandemic, according to a global survey of academics conducted by Times Higher Education.

Three-quarters (76 per cent) of respondents say they have seen lower numbers of students turning up to lectures despite Covid-19 restrictions easing across the world, while only 4 per cent say attendance is now higher.

Among students who do turn up, 54 per cent of respondents say engagement is worse than before the pandemic, with only 9 per cent noting an improvement.

THE Campus resource: Are your first-year students disengaging? Here’s how to get them back on board

THE’s survey received 339 responses, the majority of whom were based in the UK.

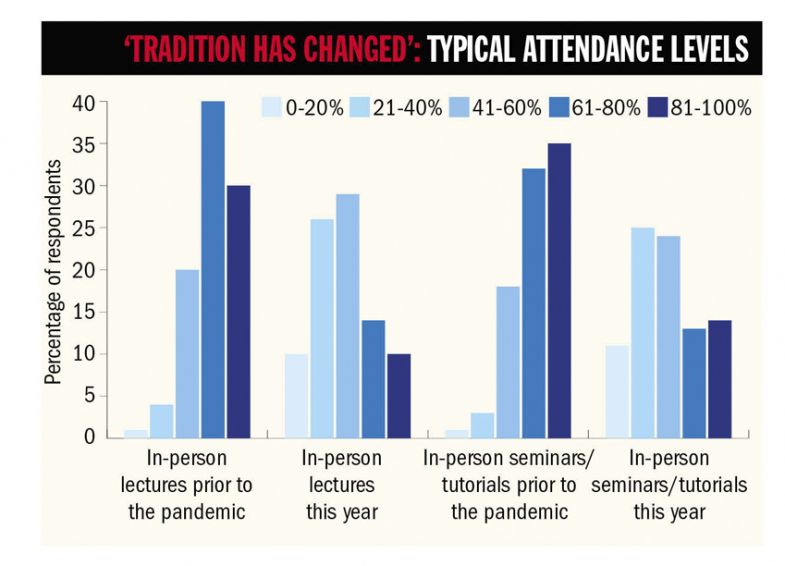

Asked what the typical level of attendance at in-person lectures is, 29 per cent say between 41 and 60 per cent of students turn up, while 26 per cent put attendance at between 21 and 39 per cent. This compares with pre-pandemic levels of above 60 per cent for more than two-thirds of respondents.

Students not wanting to come to campus was the main reason given for why academics felt attendance and participation was lower, but the number of students undertaking paid work, experiencing mental health issues or failing to do enough preparation were also cited as significant factors.

Some suggested making attendance compulsory and reducing access to online recordings as ways to overcome the problems, but others highlight that most current students had never attended a lecture, and do not know the benefits of doing so.

Paul Taggart, professor of politics at the University of Sussex, said that academics who blamed students for not attending “miss the point that there has been a substantial cultural shift among students that we need to be aware of and respond to”.

Philip Cowan, a media lecturer at the University of Hertfordshire, agreed, saying that a “culture of expectation of attendance” needed to be rebuilt.

The findings raise questions over the push by ministers in sectors such as England’s to get universities to drop blended learning and restore in-person lectures fully, and over reports in the national media about perceived unrest among students about online teaching.

At the University of Cambridge, a campaign is being planned for the coming academic year to explain the importance of attending lectures, according to Graham Virgo, its pro vice-chancellor for education.

He said that concerns about catching Covid and having to self-isolate and miss other engagements were still a major factor in why many had chosen to stay away from lectures this year, and so he remained convinced that attendance levels could recover.

“Next year we will have a new bunch of students who have no experience of lectures and those in second and third year have had very little experience, so the tradition of attending lectures has changed,” he said.

“We are convinced at Cambridge that the lecture has an important pedagogical role. We are encouraging colleagues to be flexible and experimental in their lecture delivery and we’re not saying technology is irrelevant at all, but we do consider in significant parts of the university the lecture has an important role to play and we have a responsibility to explain that to our students, as well as why attending will really benefit them.”

Among the benefits of lectures that Cambridge plans to push are their importance in combating loneliness, ensuring a student feels more of a sense of belonging in their department and that they provide the chance to hear from exceptional lecturers who are experts in their field.

Other survey respondents say universities need to be more flexible in their approach to teaching because many students had embraced the benefits of being able to watch lectures whenever they liked. One idea suggested by many involved revising academic timetables so students had several lectures on the same day, which would make it more worthwhile for them to make the trip to campus.

A life sciences lecturer in Ireland, who said that attendance in her lectures had dropped below 20 per cent, said her students were taking paid work during timetabled lectures before catching up on studies at night-time. She suggested students should take fewer modules per year so they could better balance their education with other commitments.

Another respondent, a UK-based business lecturer, agreed that the rising cost of living and tuition fees had forced students to work part-time more often and more extensively, leaving no time for them to attend or prepare for classes.

She also felt that the online delivery of lectures had “created the impression that classes are like a movie – you watch it live or on-demand and are not supposed to actively engage”.

Several respondents said the experience of being in class should be made superior to watching the recording, with more of a focus on engagement and participation using question and answer sessions and group discussion.

“We find higher attendance of tutorials in weeks in which the tutorial activity includes working on their group project,” said Janice Loftus, associate professor in the school of business at the University of Adelaide.