Chinese university presidents have described themselves as “dancers with chains on our legs”, warning that the influence of government-appointed party secretaries leaves them with little real autonomy.

Fifteen presidents who offered rare interviews for a new study said that much-heralded reforms ostensibly designed to loosen Beijing’s grip on higher education institutions were “largely symbolic” and have had “little real impact” on the ability of institutions to self-govern.

The leaders of five national top-tier universities and 10 provincial universities, quoted in China Quarterly, complained about an “absence of genuine autonomy” because any moves to enact “devolved powers would be viewed by superiors as disrespectful or as a betrayal of the [Communist] Party and party ideology”.

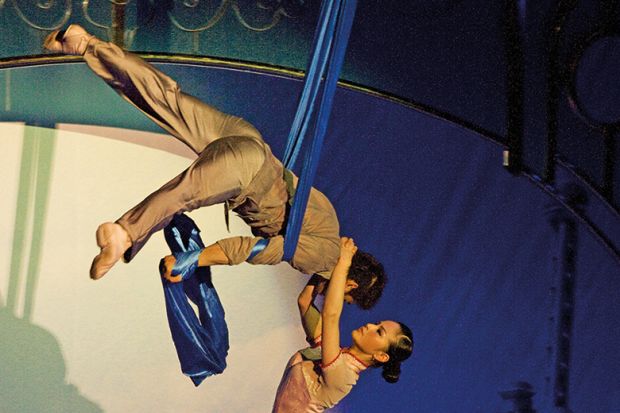

This led to “institutional inertia” because university presidents were concerned “about being seen as unnecessarily ‘rocking the boat’”, with institutional heads comparing themselves to “dancers with chains on our legs”, the paper says.

“To be honest, we don’t want to stir things up,” explained one university president quoted in the paper, who said that any reform “tends to affect employees negatively, [meaning] I could be criticised and [the government] could cut the amount of government funding we receive”.

“It’s safer to do nothing,” admitted another university leader, who said that his “official career may come to an end, or I may get demoted” if someone complained about reforms “disrupting the university”.

“Those who take the initiative tend to be punished…and those who do nothing get promoted,” observed another president.

Ten of the 15 presidents interviewed admitted that they were reluctant to initiate new proposals because it could affect their career. Many cited the influence of government-appointed party secretaries based in each university.

One president said that his plans to use more original English-language textbooks were blocked by government officials and that he was warned “not to go against mainstream ideology”.

Another’s proposals to introduce peer review in research, rather than rely on the judgement of internal university administrators, was also rejected.

“We are servants and subordinates and the government is our master,” concluded one university president.

Party secretaries at the 15 universities also offered interviews, with one referring to the party’s “absolute leadership” over institutions. Another insisted that party control was vital because an “ideological war between us [and the US] is always on, and can be a matter of life and death for our regime”.

Frank Mols, senior lecturer in political science at University of Queensland, who co-authored the paper with Hu Jian, from Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, said the interview indicated that an “impressive series of official reforms to increase the autonomy of Chinese universities…have had remarkably little impact on everyday practices”.

“Our research revealed that university presidents are hesitant to enact the authorities that have been devolved to them, out of fear this might be regarded by their superiors as going against party ideology, or challenging established informal norms and expectations,” said Dr Mols.

后记

Print headline: ‘We don’t want to stir things up’