Collaboration is the lifeblood of research. By seeking out partnerships with like-minded institutions around the world, universities can build on their academic strengths and support an international ecosystem of innovation

Global problems require global solutions, and if higher education is to meet the challenges facing 21st-century society, collaboration with like-minded institutions will be critical. Amit Banerjee, pro-chancellor at Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan (SOA), a private university located in Bhubaneswar, India, says partnerships are key to innovation and delivering impact.

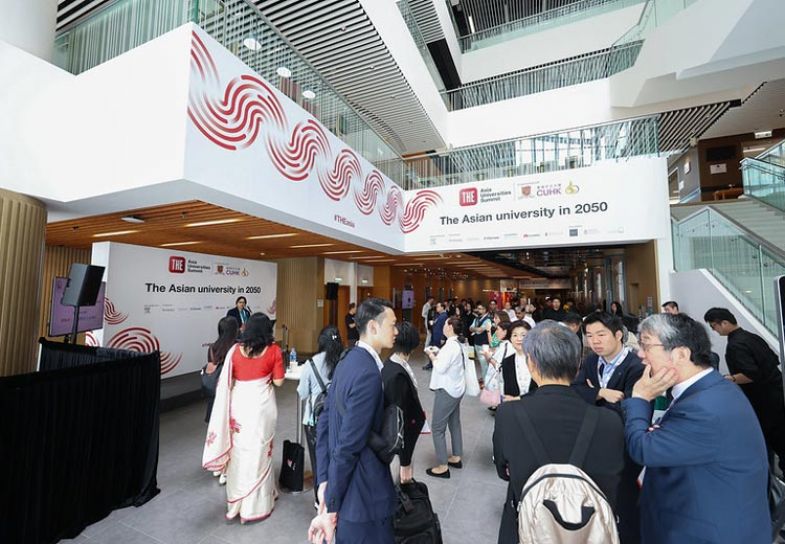

The opportunity to speak face-to-face and broker such collaborations is why Banerjee’s institution has a presence at the country pavilions showcase at THE’s Asia Universities Summit 2023. The country pavilions showcase the higher education institutions that are using THE’s data analysis to help them identify potential partners, discover suitable collaborators and demonstrate their institutional strengths.

“You do not get the chance to meet people physically from other parts of the world unless you have got a pavilion like this,” he says. “Innovation is not simply about progressing yourself. Innovation is about taking the entirety of mankind on a progressive pathway. It is a global ecosystem that we need to establish, and it is very important to stay in touch with other universities.”

“Anybody in any corner of the world has the responsibility and also the right to access what is happening at the other end of the world,” Banerjee adds. “To that end, it is extremely important to find out what like-minded people in other parts of the world are thinking and to get in touch with them.”

SOA – where the focus is on quality education and research – is a relatively young institution, having been granted university status in 2007. It serves more than 15,000 students and has a burgeoning international reputation for excellence. The university prides itself on having a global outlook. Banerjee believes it is incumbent on all universities, no matter where they are located, to adopt an international perspective and to mine the potential of networks.

For the past seven years, the 17-year-old institution has maintained a consistent presence among the top 25 universities in India, according to the Ministry of Education’s National Institutional Ranking Framework. In 2023, it received reaccreditation from the National Assessment and Accreditation Council, with the prestigious A++ grade.

Manojranjan Nayak, the founder of SOA, established the Institute of Technical Education and Research (ITER) in Bhubaneswar in 1996 with the aim of offering high-quality education to students in Odisha. Additional institutions were subsequently added, offering disciplines such as medical sciences, dental sciences, pharmaceutical sciences, biotechnology, nursing, hospitality and tourism management, legal studies, agricultural studies and veterinary sciences.

The ITER is now regarded as a top institute for engineering and technology in the region. With a primary emphasis on research, the university has established 16 research centres dedicated to 26 focus areas. Research initiatives within these centres are supported by grants from external organisations such as the Department of Science and Technology, Department of Biotechnology and Defence Research and Development Organisation.

Nayak graduated from the National Institutes of Technology with an electrical engineering degree. He then completed a master’s in computer science at the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, followed by a doctorate at Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology. Nayak set up SUM Ultimate Medicare, a ground-breaking one-stop hospital in Odisha. He also runs The Prameya, a daily newspaper published in the Odia language, and News7, a 24-hour Odia television news channel.

The country pavilions offer industry leaders the chance to share best practice and insights into their nation’s higher education sector. In 2020, the National Education Policy in India liberalised the academic ecosystem and encouraged a spirit of academic freedom that SOA and others are keen to capitalise on. “It is a completely revised version of what we have been following in the past,” Banerjee says. “There is a lot of freedom of expression and you can interchange your disciplines. You can have a multidisciplinary approach.”

The reforms have allowed India’s academics to pursue a wider area of study, add knowledge from different disciplines and bring that to bear on their subject. “You can do some micro or blended education,” Banerjee says. “For example, I am a doctor, but I may be interested in material science. I can do some amount of microstudy in material science, then learn a little more and bring it into my own profession.”

Transparency is key to the success of international partnerships. Both partners must take responsibility so that research projects are funded through to their conclusion. Banerjee says partnerships can be easily made but they can be difficult to maintain, and concludes that all parties should be guided by positive research outcomes.

Find out more about Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan.