A few years ago, I had reached the stage of despair over the deterioration of the university system in my own country, Nigeria, under successive regimes of both civilian and military orders. Even the basic, campus social life had broken down, a condition that I tried to summarise in the title of a public lecture that went: “Descent of barbarism and end of the collegial”. Educational standards had plummeted so low that the word “illiteracy” had become current within – not only outside – the ivory towers, leading Unesco to classify Nigeria as one of the nine countries that together accounted for 70 per cent of the globe’s illiterate population.

We do not need to be reminded that primary and secondary education form the base material for the intellectual quality of intakes into the tertiary institution. When deterioration in those two tiers is compounded by the fact that those tertiaries indulged in any excuse to foment strikes by faculty, students and workers (ignoring civil wars for now), we should not be surprised that institutional closures, which have become the norm, guarantee that a three- or four-year degree course is often guaranteed to run into five or six.

Yet while the laboratories shrank in equipment and the libraries stagnated from lack of sustenance, the mosques and churches within and immediately outside the campus grounds multiplied and flourished. The only books that seemed to be under guaranteed replenishment were the Koran and the Bible. The born-again phenomenon saturated campuses, as “Hallelujahs” competed with “Allahu Akbars” in raucousness across student halls and converted lecture theatres, destroying the peace and quiet required for concentrated study and reflection.

Even faculty members raised churches, and added “Pastor”, “Right Reverend”, “Prophet”, “Archbishop” or “Supreme Alhaji” to their academic titles. Recruitment of new faithful was at fever pitch, and peer pressure was relentless in overcrowded dormitories. Sermonising tapes were often glued to the ears of these captives during hours of sleep, so that the last sounds they heard before collapsing at night and the first on waking were the hypnotic voices of their clerics. This regimen scrambled their already overloaded brains still further, turning them into zombies: in some cases, turning them permanently off their purpose in those institutions, having been brainwashed into a line of thought that made academic achievement a sin of pride: a failing that could be expiated only by giving themselves up completely to one of the contending supreme deities.

Something had to give, and it was not long before religious rivalry took a physical turn, threatening to set institutions on fire. Crusade countered jihad. The signs were already ominous: they would inevitably evolve into an agenda of anti-scholasticism that – if it is any consolation – now threatens the very notion of objective instruction across the globe. At the campus of my alma mater, now known as the University of Ibadan, a Protestant chapel was built, to be joined later by a Roman Catholic church and a Muslim mosque. About 20 years ago, political agents provocateurs invaded the campus with their bags of money and chronic intolerance. They attempted – and succeeded for a while – to whip up a potentially violent confrontation between different sets of believers, and came close to unleashing a religious war by giving ultimatums for the removal of a cross, on the grounds that such a symbol polluted the purity of Muslims’ worship since it stood in their line of vision when they looked East. The then minister of education summoned the vice-chancellor and ordered him to remove the offending symbol. The principled response of that vice-chancellor was as follows: “Sir, it would be far easier to remove me as vice-chancellor than to uproot that cross from where it stands.”

The symbols of both Christian and Islamic religions have remained in place ever since, a testimony to the triumph of collegial integrity, and a repudiation of mindless fanaticism and bigotry at the highest level of administration. This, the cohabitation of those two contending symbols, like the cohabitation of opposing ideas and philosophies, is the very essence of the university idea.

Those who seek to understand the origins of the longest and most vicious anti-intellectual, anti-creativity movement unleashed on the world of learning, and on Africa especially, in recent times must learn that the enemy has always been within. Names like Daesh, Boko Haram, Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army have their roots and propulsion from within the supposed citadels of learning, with the latter serving as either instigators or collaborators. We breed these groups, either through complacency or through resignation. If, on entering the ancient city of Timbuktu, one of the earliest learning institutions on the black African continent, a member of the Islamist group Ansar Dine headed single-mindedly for the ancient libraries of Mali on a triumphal march whose climax was to be the torching of their contents, let us always remember that others, supposedly educated, have softened – and are still softening – the ground ahead of his perverse mission. It was only thanks to the heroic commitment of a few dedicated servants of the Muse of Learning – to cloak-and-dagger operations involving deception, diversion, sometimes risk of death – that hundreds of thousands of these ancient collections were saved. Without those unsung heroes, the intellectual heritage of Mali – and of the African continent – would be today mere ashes of the past, and a chorus of impotent lamentations. And let no one believe that the menace is over, or that the enemies of the university idea are war-weary. How can they be, fired by extraterrestrial zeal and moved beyond the claims of reason?

No one will deny that in time past the university never encountered an agenda of human elimination remotely close to what was experienced in Kenya, at Garissa University College in April 2015, when the religious night raiders of Al-Shabaab, reading from a list that was undoubtedly provided by some of the college students themselves, called out the victims one by one and knifed, bludgeoned and shot them to death. In general, one’s mind constantly reverts to the easily forgotten foretaste of religious ecstasy of that morbid kind, which has now become rampant on the African continent, and against whose background we find ourselves frantically roaming far and wide for enduring solutions.

My prescription is not complicated. It proposes a year of materialist induction to detoxify incoming minds from inherited or acquired religious zealotry. Note, I do not say “religion”, simply its dehumanising temperament: a “divinely mandated” intolerance that is so easily turned towards heeding a call for the elimination of non-adherents. One solution might be some branch of lobotomy that targets wherever the gene of intolerance is located. But we can opt instead for a year of induction, a pre-enrolment obligation where the student is taken through a course of alternative explications for the seeming mysteries of phenomena – including the human.

While universities of the air have laudably enabled access not only to knowledge but to the democratisation of its formal acquisition and structures of adjudication, their retrogressive counterparts have been no less assiduous in their own conversion of that open facility, operating through the internet. Their “graduation” tests alone attest to the effectiveness of their recruitment into the mono-discipline that I sometimes refer to as the Academy of Morbid Instruction. Our target is unavoidably the mind: how to retune it and render its mentors’ modes of instruction – and content – ineffectual.

“Catch them young” should be more than just a slogan. It should become a declaration of purpose and should admit of no apologies for its materialist orientation. It is no more than an experimental model, based, however, on our experience since the colonial era: the multi-directional undertaking of the decolonisation of learning, all the way down to the current blood-stained rampage of theocratic philistinism. It would borrow principles even from the ancient beginnings of the university movement. The sheer horror of contemporary narratives from living witnesses, such as Karima Bennoune, author of Your Fatwa Does Not Apply Here: Untold Stories from the Fight against Muslim Fundamentalism, or Wafa Sultan, writer of A God Who Hates: The Courageous Woman Who Inflamed the Muslim World Speaks Out Against the Evils of Islam, have contributed to what might seem an extreme approach to what is now a galloping menace. But the greatest instigation for me has been the once unthinkable ordeal of my own nation, in the form of an affliction called Boko Haram, which in effect crippled intellectual life across huge swathes of north-eastern Nigeria, beginning at least six years ago. Let me emphasise also that the time for even a glancing recourse to political correctness is long past if ever it had a place in human discourse, particularly within the university environment.

Here is our optional proceeding. On entering the university, incoming students would be made to leave their books behind. They would be free to use the library, but restricted to a reference section, carefully selected for its multidisciplinary scope. It is difficult to conceive how electronic access would be managed since, ideally, all of the cohort should have access only to the same works of reference. However, this is not an insurmountable problem for dedicated management. Each student – and they should be from all available academic compass points, no matter their ultimate specialisations – for the first time engages the immediate environment as autonomous entity: indeed, as the sole storage of materiality, from which abstract ideas and, hopefully, transformative concepts can emerge. The students may choose to relate it to externalised origins, such as a divine Super-Mind, but only after that first year, when they would have undergone tests that declare them free of the virus of dogma and extremism, and thus fit to embark on other disciplines.

We are speaking of an uncompromising materialist foundation in students’ encounter with phenomena. We are speaking of a closed, monkish existence: a period of mental stimulation, during which students are schooled in the powers of observation, discovery and comparison, including the histories of the very material entities that have shaped their particular micro-environment. This would be taught – actually, more of a seminar form of exchange than teaching – within the scope of what the students’ predecessors made of such material surroundings: how they have been neglected, altered, enhanced, beautified or degraded by the human hand, and, hopefully, how such environments, in turn, have shaped those predecessors. The students would be required to study how other minds – mostly their colleagues’ – respond to the same environmental particularities, and exchange notions about the varied entities they encounter during their campus strolls: a rock tumulus, a stream, an artificial lake, a frog, a butterfly, a tree through its seasonal changes, a lizard, moulting snakes: whatever crosses their paths.

While, obviously, their deductions would be influenced by early home upbringing – guaranteed to include religious indoctrination – they would at least be compelled to apply their developing individual intelligence to questioning, reinforcing, adjusting or repudiating received lessons. They would engage others in disputations on a platform of equality of probabilities. Received knowledge would score below deductive arguments, while claims of Revelation in any form would earn the pupil instant expulsion. This exercise in intense mental discipline, based on the interaction of the mind on a limitless yet delimited zone of occupancy in near-complete seclusion, would form the character of the student crop, and thus, the intellectual signature of my institution.

The question that comes up again and again, and has done since the beginnings of formal learning, is: to what purpose, the university? The answers are not so categorical, since they tend to shift with time. If we begin with the religious order, which was the original home of early universities, the answer could be summed up as “to serve God better”. But objectively, and in a spirit of equity, the secular basis deserves its own time, and in a mode of concentration that compensates for centuries of theocratic privilege, however thinly disguised. Subjectively, to put it harshly, the theocratic has exacted such a heavy toll on the intellectual pursuit, both in ancient and recent times, that drastic strategies are mandated for weaning the young mind away from the Revelationary overlay on material manifestations, even at the unacknowledged, subliminal level.

That said, secular ideology has sometimes proved no less tyrannical on the mind. This was the case in the Soviet Union and its satellites under that other form of fundamentalism, the Stalinist-Leninist legacy, which created a very special breed of the learning generation, whose personality was perhaps best captured in the product of the Komsomol. That model of youth mobilisation found facile emulation in various degrees among would-be revolutionary regimes in our Third World, some of which sought to outdo even the Soviet model in conformity of thought. Within such institutions, intellection was equated with the ability to view the world virtually through the prism of, for instance, dialectical materialism and class conflict – and this included subjects as far apart as mathematics and handicraft. It seemed an impossible feat, but, by some of the most tortuous and strained dialectical processes (although a will to the suspension of reason would be a more accurate description), it was achieved – at least to the satisfaction of the controllers of such institutions.

History in the Soviet region underwent the most egregious forms of revisionism, to the extent that whatever did not fit into the tidy schema of socio-economic development, or the prevailing theory of social formation, was simply deemed not to have taken place! As the state grew more confident of its own powers and global destiny, such excesses would be abandoned, but, by then, it had taken a not inconsiderable toll on the intelligentsia, who formed a dissenting minority. The overall purpose of higher education was straightforward: to manipulate knowledge into a utopian awakening of the universe and a justification for whatever socio-political measures were considered necessary for that day of awakening – including the liquidation of some of the Soviet bloc’s finest thinkers, poets, and artists.

Of course, this could not endure, and the cracks within such hermetic thinking began long before the fall of Berlin Wall. Reformation spares neither Pope nor Mao. Sooner or later, it arrives. However, to be enduring, reformation begins from within. Take the US, where centuries of exclusion and denigration of socio-historical knowledge that related to a large section of the world – the African – were dramatically reversed. It came about as a result of the agitation, sometimes violent, of the African American population. Libraries and classrooms were progressively purged of racist literature, while an infusion of the authentic material – historic and cultural – about the African continent became a requirement of higher education institutions. Departments or institutes of African studies sprang up in numerous colleges.

The movement led to a reassessment of the canonical approach to literary and cultural material that favoured, near exclusively, the European world. Disciplines that stretched from black history and politics to African architecture, Egyptology, black aesthetics and traditional agriculture were now eagerly embraced. This led to the progressive transformation of what, even into the 1970s, was still a deeply racist society and a divided populace. Until then, consciousness of black reality was marked by a condescension that percolated through to the psyche of the descendants of African slaves, creating, for the most part, an apologetic attitude, almost tinged with a sense of embarrassment of origin. But, lo and behold, a dramatic change of the collective social psyche began to extend beyond the black population, a large portion of which, until then, had been coerced into accepting the valuation of white intellection and, both implicitly and in practice, the inferiority or non-existence of a black civilisation or history. With this revolution, the privileged white society itself became, ironically, a beneficiary, discovering and sometimes adopting a totally new realm of societal values, new ways of viewing history, new performance and musical modes and other artistic styles: even dress tastes and culinary traditions. It became fashionable to be able to speak a few words in Kiswahili.

Today, the critical issues are less abstract. The survival of the university idea has moved beyond the hypothetical and detached postures now that universities find themselves often on the front line of sudden and brutish violence. At the centre of it all is the mind. It is the mind that addresses the question: why is such and such possible? Historically, sociologically, philosophically and even psychologically, the mind must seek and find answers, and that task points to one summative destination: mankind in its own self. That living, breathing and conceptualising organism that we call the human entity: can we really boast that it has been studied holistically? If such a claim is made, then the study has proved so far a failure. It has failed to come up with an answer to that excruciating question of historic bafflement: how is it possible for this to happen? I am not speaking of the study of humanism but of mankind itself.

Why do some of the Muslim faith so passionately detest learning even when their Prophet preached respect and protection for “People of the Book”? If the university were able at least to insert that question into a field of study as a permanent requirement, it would have contributed in no small measure to an intellectual model that could be followed in other zones of irrational conflict. And one sustainable approach to the study of mankind is to observe and analyse how minds respond to actual phenomena: in short, to objectivise the workings of the mind.

We are thrust back, it seems, to a purposeful or, shall we say, utilitarian approach to the university idea, but on a universal dimension. Once grounded in the material, as a common denominator of the mind’s resource functioning, we are on firm grounds to bridge the gap between the potential for new conceptualisations and those spiritual orientations that make it easy for outside forces to muster recruits within our higher education institutions.

Above all, let us remember that this is an ancient problem that has merely acquired a renewed urgency, and that it is often no more than a manifestation of the perennial struggle for power and domination over others. The particularities – the manipulation of religious irrationalities – remain the same. But, today, the consequences rebuke our history of complacency. And so the university of the future should become, if you like, the decompression chamber between received knowledge and the self-retrieving world of objective enquiry.

The ultimate destination is a simple model whereby incoming minds are made to undergo a contemporary version of the coming-of-age ritual, in which that mind is compelled to recompose the world in its own image, constructing an individual template against which tested and untested – that is, dictated – knowledge is bounced.

We are speaking, in short, of a fact-based, reality-informed project of self-enlightenment, which enables us to remain on terra firma, not seek solutions in the hereafter. Where do we begin? We could do worse than let science, in tandem with her close sibling facilitator, imagination, instruct us. The world’s most intriguing scientist, Stephen Hawking, speaks of science “transforming our perception of the world” and asserts: “We share the same spirit. What is important is that we have the ability to create.” I would extend those parameters only slightly, to read: “We have the ability to recreate the world.”

That sums up my vision of a future university, into whose lap surely falls the primary task: a future world discovered, attainable in the present.

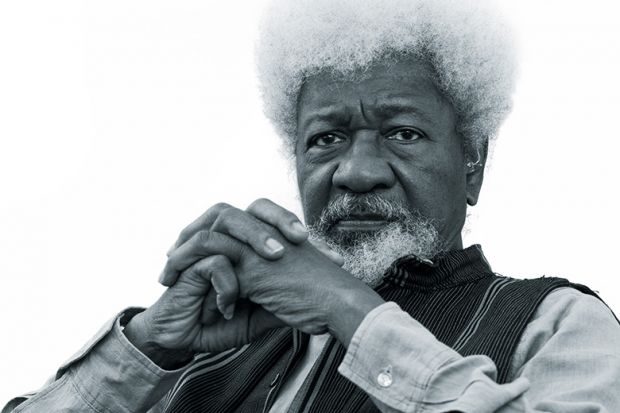

Wole Soyinka is a playwright and poet. He was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature. He was professor of comparative literature at Obafemi Awolowo University in Nigeria between 1975 and 1999. He has also held positions at Cornell University, Emory University, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, New York University and Loyola Marymount University in California. He has taught at the University of Oxford and Harvard and Yale Universities.

This article is an edited version of a speech Soyinka gave at Times Higher Education’s BRICS and Emerging Economies Universities Summit, held at the University of Johannesburg earlier this month. After the speech, Soyinka gave a video interview to THE.

后记

Print headline: Against intolerance and indoctrination