Until recently, when the UK thought about its place in the world, it viewed itself politically and culturally as somewhere between the US and Europe.

That orientation has been thrown into confusion by the ugly path of US politics since 9/11 and the myriad democratic, economic and social problems that, from Catalonia to Crimea, have engulfed Europe. One consequence is that students, like everyone else, want to know more about the UK’s historical relationships with the wider world. Interest in imperial legacies and organisations such as the Commonwealth, which is holding its heads of government meeting in London this week, are central to this. Yet while the appetite is there, sating it can prove challenging.

Peter Yeandle, a lecturer in history at Loughborough University, acknowledges that there has been a “media kerfuffle” in recent years over moves to “decolonise” the curriculum, remove the statues of Cecil Rhodes from the universities of Cape Town and Oxford and rename a concert hall in Bristol originally named after the slave trader Edward Colston. However, in his view, “there is very little that addresses the history of decolonisation head-on, at school level”.

Yeandle is the author of Citizenship, Nation, Empire: the Politics of History Teaching in England, which illustrates that this deficit of understanding is nothing new. Imperial politics split parties in a similar fashion to Brexit: even in its 19th-century heyday, the empire was too thorny a subject for the majority of textbooks to be anything other than vague about. This vagueness continues to bedevil postimperial legacies, ensuring that, for all the enthusiasm, undergraduate history teaching in England and Wales begins at a low base.

Equally, it is difficult to understand decolonisation unless you have a clear idea of how imperialisms worked. In schools, imperialism tends to be characterised as a 19th-century phenomenon; in the 20th century there is just too much going on for the syllabus to cope, so it has been too easy to forget that British imperialism endured to the end of the 20th century and may only die completely with Queen Elizabeth II. One problematic realisation is that, if you wanted to pick up the UK’s relationship with non-European countries by tracking processes of decolonisation, you might need to explicitly and self-consciously colonise its 20th-century history books first. For instance, 1945 would be bound up with, if not become, the British people’s post-colonial moment.

At present, this lack of coverage means that when students get the opportunity to explore further at undergraduate level, the groundwork has usually been laid by something akin to Niall Ferguson’s Empire. This is not to be snooty about popular books or television shows, just to acknowledge that they can be difficult to discuss with any flexibility. Their invariably taut founding premise – in Ferguson’s case, the necessity of gunboats for globalisation – defines the parameters of future debate. You junk the longer report on the imperial legacy and turn straight to the executive summary. No wonder there is such hunger for something more.

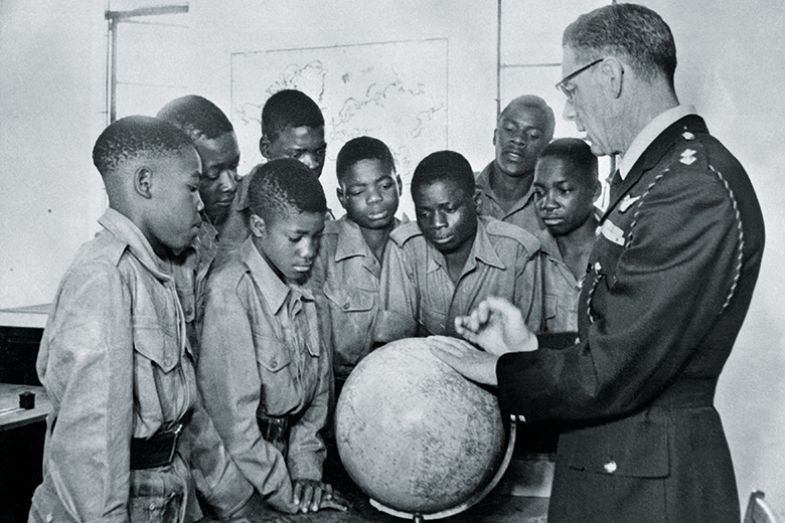

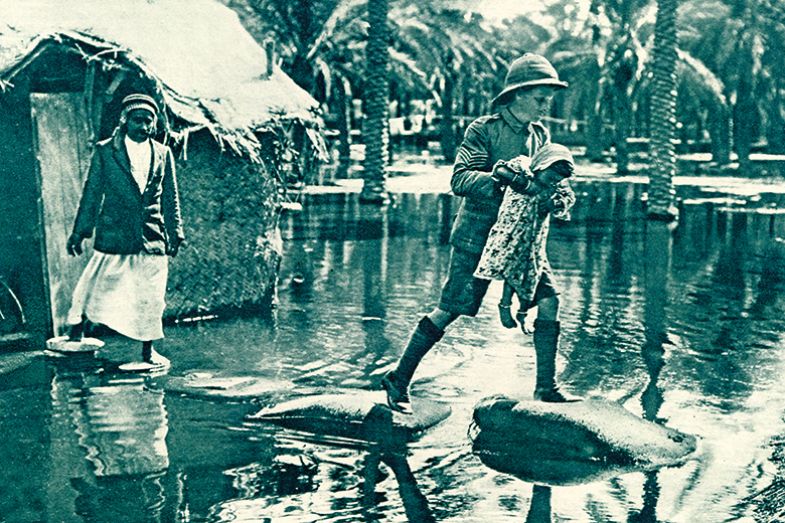

Unsurprisingly, the lack of entry-level undergraduate texts, along with the centrality of Google to student research, has also opened a space for non-academic histories. One digital source that has become influential among many students is the Crimes of Britain project. This website, set up in 2015 to monitor “British imperialism of the present day and [revisit British imperialism] of the past”, publishes a daily feed of outrages. The subjects of posts stretch from memorials to anti-colonial protesters in India, to British atrocities in Ireland and recent military interventions in the former Yugoslavia. The broad thesis is that imperialism as a British mode of interacting with the world has never gone away; instead it reconfigures itself into new guises, such as humanitarianism.

“My initial idea was to target Irish history, but I quickly realised that it was tied up with this bigger story of colonialism,” says the project’s founding editor. “Aside from Kenya – maybe India – the impact of colonialism is not really discussed, and the scale of the British Empire is barely acknowledged.”

Although he did not study history, the editor cites the work of writers such as Ernie O’Malley, an Irish Republican Army officer during the Irish War of Independence, and Indian politician and former United Nations official Shashi Tharoor as inspirations. He also points to a generation of online activists that operate platforms highlighting European and American atrocities. The sheer geographical range the site covers, along with the range of materials reproduced – stamps, photographs, posters, film footage – has given this intervention a significant reach, even if most academic historians would object to the framing. To meet the demand for information from a readership primarily made up of “younger or much older people, Irish Republicans, middle-class Indians and English lefty types”, the editor has recently completed the production of a fully referenced book. What began as a hobby is slowly morphing into something else.

One of the things that Crimes of Britain has done is expose the scale of amnesia about British imperial legacies. The absence of coverage of such issues in British school textbooks is a reminder that partial histories are not just things that exist in authoritarian states. When the website ran a poll of its readers educated in the UK, only 8 per cent of the 12,000 respondents said they had learned about empire at school. Compare that with the YouGov survey in 2016, which found that 43 per cent of British people believed the British Empire was a “good thing” and you get an explanation of why Crimes of Britain evokes such a strong response. If you know next to nothing about the British Empire, but instinctively believe in the UK as a benign force, the site is an unpleasant awakening. Death threats have forced the editor to take precautions with personal safety, such as hiding his identity. And a series of complaints have led to Facebook several times suspending the site.

“The fake news and conspiracy theorists exist [on Facebook, but efforts to stem them are] also an excuse for a crackdown on anyone who deviates from the establishment viewpoint,” says the editor. “What I hate is that colonial crimes are made into one-offs, or big, bad villains; much as I dislike someone like Churchill, you have to understand him as a man of his time. Attempts to portray him as a one-off monster diminish the true evil nature of the British empire.”

As unlikely as it may seem on the surface, the controversy that Crimes of Britain provokes is strangely analogous to that faced by a project of an entirely different orientation at the University of Oxford on how to conceptualise imperial legacies. The “Ethics and Empire” project run by Nigel Biggar, Regius professor of moral and pastoral theology at Christ Church, Oxford, has generated enormous amounts of controversy, within academic and media circles. In its own estimation, Biggar’s project is concerned with examining the historical phenomenon of empire as opposed to an ideological construct of “empire”. As with so much else in the field, addressing arguments about the legacies of imperialism seems to run slightly ahead of understanding its operation but it’s the “ethical” dimensions of the project that appear to have most infuriated its critics. In a recent opinion piece in The Times, Biggar reports that “a senior academic at one of Britain’s most prestigious universities” reacted to the news of the launch of his project by tweeting: “OMG, this is serious shit. We need to SHUT THIS DOWN”, and went on to dismiss his scholarship as “supremacist shite” and “vomit”.

In response, the Daily Mail published an article naming the academic as Priyamvada Gopal, reader in anglophone and related literature at the University of Cambridge. The article, which prompted a fierce backlash from academic and student supporters, condemns Gopal as a “prolific internet troll” and cites the incident as another example of “Left-wing nastiness” in UK universities.

“My interest in these issues is as an ethicist interested in questions of right and wrong,” Biggar tells me. “I’ve done work on the rights and wrongs of war, and the notion that the reality of Empire was any less messy and confused is alien to me. There’s no doubt that the British Empire was responsible for terrible things.”

What appears to make historians most uncomfortable is the way in which the project is self-consciously grounded in a Christian perspective. Biggar is an Anglican priest whose past work has addressed subjects such as post-conflict reconciliation. This is not the sort of frame that most university-based historians in the UK, who, as a cohort, weigh the experience of the past on overwhelmingly materialistic scales, are ever likely to favour.

The opprobrium that Ethics and Empire has attracted, from Oxford scholars and anticolonial student groups, as well as from an international network of imperial historians, appears to have isolated it. The project operates through invitation-only seminars, with opportunities for public participation non-existent. This is, at least partly, because of the likelihood that these events would otherwise become a locus for protest rather than discussion. Biggar tells me that he has received many private messages of support, but even this seems of a piece with the depressing pattern that ensures imperial legacies are never openly and accessibly examined.

“The fact that I am not a historian made me a bit naive and blinded to the ferocity which met my views, as I wasn’t aware of the extent to which certain reaches of an academic subject like history are dominated by uncompromising positions,” says Biggar. “I have learnt to be more sensitive to the experiences of subjects of empire from post-colonial thinking, although the post-colonial mistake can be to assume that all the subject voices say the same thing.”

It is not just the UK that suffers from a lack of intellectual and cultural space when it comes to opening up historical discussions about decolonisation and imperial legacies. When the UK’s Colonial Office devised “Operation Legacy” in the 1950s to identify, erase and repatriate compromising material from colonies moving towards independence, the obvious intent was to protect colonial staff and the future reputation of the UK. However, another motivation was to preserve good relations with the nationalist governments that were often ushered to power post-independence. Discussions on the political and administrative transfer of power remain difficult in many of these countries; ranging more broadly over the social and cultural aspects of decolonisation, since independence is almost impossible. In Singapore and across south-east Asia, for example, the archival pickings are even slimmer than those found in the UK. When the British Navy incinerated truckloads of Malaya’s colonial records in 1957, it worked to the long-term advantage of the new political elites, too.

Ironically, if young scholars in south-east Asia want to address decolonisation directly, they tend to do it in the West because wrestling with new nationalist histories at home can be a career-threatening move given the tendency of post-colonial governments to take “you’re with us or against us” stance regarding criticism. The result is that local comment tends to emerge from alternative historical practices instead, such as the contemporary art world. In Singapore, for instance, the artist Shubigi Rao produces works focused on the destruction of libraries and archives.

“There is a very strong discourse on decolonisation in south-east Asia that is increasingly seeping into the thinking of Asian archives and museums,” explains Rao. “But the nature of the discourse can be rather ‘unhuman’ because it is much more comfortable to critique ideologies than to look directly at human-centred actions or behaviours.”

Rao’s interests range across archaeology, early modern science and natural history. The installations she produces involve books, text, drawings, etchings and pseudo-science machinery, although more recently, she has been collating a very intimate testimony of archival destruction. These histories are based on the contribution of small numbers of eyewitness volunteers. The idea is to get away from “big” histories that rely on large archives and introduce something less controllable, more contradictory, and more obviously emotional and subjective to the historical record. Her point is that while libraries and archives represent established ways of managing history, one antidote is to create a kind of peer-to-peer alternative: archives able to survive the 21st-century equivalent of being incinerated by the British Navy. This is history aggregated as if it were your duty as a serious moral individual rather than a bureaucratic skill that can survive the scrutiny of academic peer review.

“I often get invited to talk about decolonisation in Europe and asked to “unpick” things. But I am rarely given the choice of what I get to unpick or unwrite,” says Rao. “It’s a systemic problem that if you’re Asian, you only get invited to engage on certain topics.”

According to the Nigerian writer Kole Omotoso, the widespread inability to understand historical processes of decolonisation is tied up with a fundamental ignorance about how governance and global power works. In this reading, mass confusion is the inevitable consequence of the friction between modern notions of governance and much older cultural practices. It’s what happens when long-established chiefs, emirs and all-powerful emperors rub against the universalised jargon of international corporate bureaucracy and modernistic expectations of the post-colonial world. As Omotoso points out, this confusion can be linguistic: “English sometimes disrespects its political leaders; Yoruba never disrespects its obas or emirs.” Amid this perplexity, generalised ideas of groups identified as being “in power” come to replace any kind of critical discernment of the responsibility of governance and the appropriateness of deference towards those who rule.

“The Commonwealth touched people in Nigeria, especially the educated class. The first newspaper in Yoruba was launched by an Englishman named Townsend,” Omotoso tells me. “But what I found in South Africa was more of a sense that white people were this, that or the other, without discriminating between those in power and those without power, or people in religion, commerce [or] whatever. This is a very unfortunate understanding of the world.”

In the UK, the task of narrating the history of decolonisation and post-imperial relations requires a level of imaginative, moral and philosophical insight that may be beyond the capacity of any one discipline let alone any one scholar to address.

Sue Onslow, deputy director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies at the School of Advanced Study, University of London, tells me that the best hope for Commonwealth and imperial legacies is for them to become central to civic education.

With only two hours of history in the UK’s national school curriculum up to the age of 14 – at which point two-thirds of pupils drop the subject – space for complex new histories will always be limited. That is without even addressing related philosophical questions about how far the teaching of history should be concerned with encouraging identification, empathy and sympathetic interest.

For Omotoso, meanwhile, “what we need is a sort of Stephen Hawking cosmic view, reconsidering historical contestations across the planet as material for a collective knowledge”. This is surely a project that deserves a generous and far-sighted patron.

Disappointingly, the British educational establishment has historically remained mostly aloof from such efforts, even as it thought of itself as being inherently international (perhaps reflecting its volume of international students and the power of its publishing industry, which both rest, to an extent, on imperial networks). When the League of Nations tried to encourage the writing of international histories after the First World War, the UK declined to get involved. Equally, when the Council of Europe produced material to aid the teaching of European history in schools in the 1970s, the UK absented itself.

We are now at a stage where only 13 per cent of historians in UK universities specialise in the histories of Asia, Africa, Latin America or the Middle East. This amounts to a staggering mismatch between the UK’s international self-conception and its capacity to think about the rest of the world. These things are always relative, but it’s important to be able to distinguish between a genuine global perspective and a parochial simulacrum of one.

The cultural resistance to directly addressing decolonisation as part of understanding the UK’s place in the world is deeply embedded. But it is surely only a matter of time before the continued refusal, within education and beyond, to maturely address such questions will come to look as ridiculous as telling the story of a non-European world that comes to exist only when the West discovers it.

Scott Anthony is an assistant professor in public history at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

后记

Print headline: Historical adjustment