The MBA has undeniably had a stellar career. During the century since its invention in the US, the master’s in business administration has become a must-have for any executive aiming to take the next step in corporate senior management.

Accordingly, business schools have sprouted up across the globe. Their cohorts of older students are usually taking time out of well-established careers, marking out business schools as very different beasts from the parent universities of which they are usually a part – and which are the grateful recipients of the sky-high fees the executive market typically commands.

Times Higher Education has worked in partnership with The Wall Street Journal to gather a unique set of performance data from business schools across the world – based on metrics pioneered in the WSJ/THE US College Rankings, which are designed to explore teaching excellence and the student experience. In total, 114 business schools from 24 countries were ranked in the project, and while some prominent schools chose not to participate, the project has provided a range of data, including almost 23,000 responses to a survey of business school alumni, supported by the schools. The data allow THE to compare institutions across a range of business programmes: two-year MBAs, one-year MBAs, master’s in finance and master’s in management, and to draw rich insights into the characteristics of different institutions and courses.

The market for two-year MBAs is dominated by the US; of the 54 institutions offering two-year programmes that took part in the analysis, 44 are in the US. And their quality is underlined by the fact that US institutions occupy the top nine places in a ranking of two-year programmes based on the submitted data.

The ranking is based on 20 factors, encompassing institutional resources, student engagement, teaching environment and student outcomes.

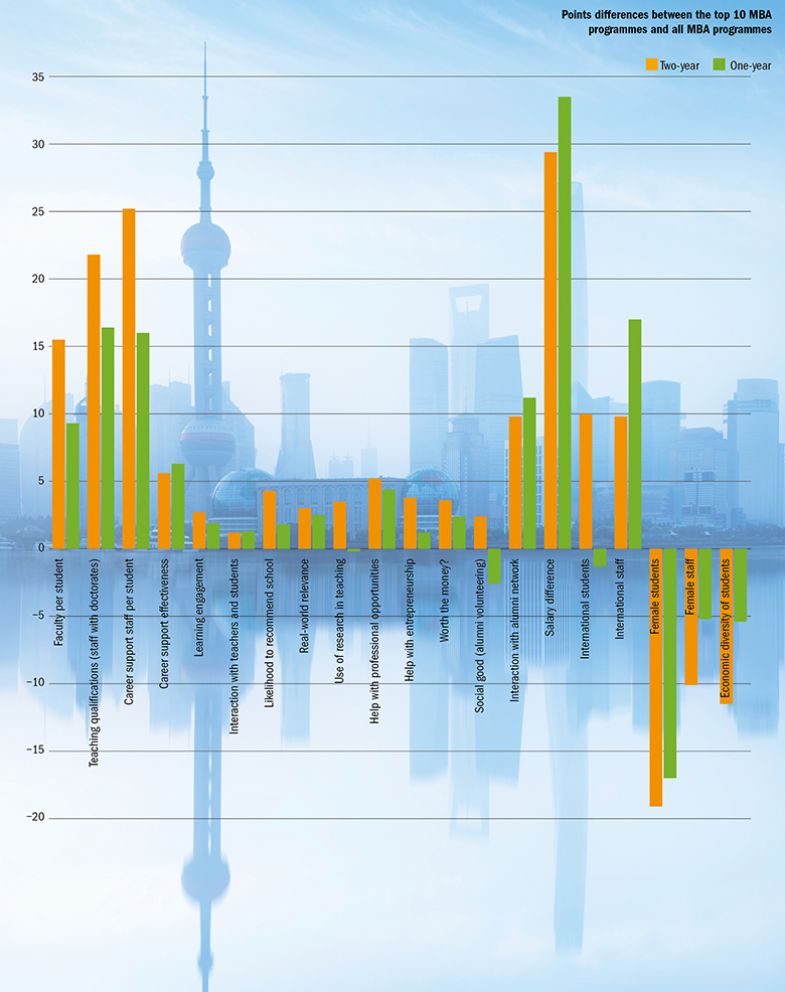

Analysis of the score differences between the top 10 two-year MBA programmes and all such programmes suggests that the strength of the top schools centres on their greater resources, their international focus, the salary boost they offer and the strength of their alumni networks.

According to Yossi Feinberg, senior associate dean for academic affairs at Stanford University, which has the top-ranked twoyear MBA programme, the key to fostering strong alumni networks is to keep class sizes “strategically small”. This allows for a “high-touch, immersive” experience and, importantly, fosters lifelong friendships. “Upon graduation, the students join a tight-knit network that creates global impact beyond the boundaries of traditional business practices,” he adds.

Cherrie Wilkerson, assistant dean of young professional programmes at Vanderbilt University’s Owen Graduate School of Management, ranked third, explains that her institution stays in contact with its alumni through events in the cities where graduates concentrate, adding that a programme whereby alumni offer current students one-to-one mentoring also ensures that those alumni stay in touch with the university and each other.

Performance factors: where top MBA programmes stand out

Outside the US, the China Europe International Business School, based in Shanghai, is the highest-ranking institution for two-year MBAs, at joint 10th. Its vice-president and dean, Yuan Ding, says that a lot of the institution’s success is down to two factors. One is China’s economic growth, and the opportunity the school offers to international business students who want to tap into that. The other is the institution’s governance, whose emphasis on autonomy and academic freedom makes it unique in the region. “Our faculty have very fertile ground to do their research and express their opinion,” he says. “We are also now moving from knowledge dissemination to knowledge creation.”

The institution’s prominence in THE’s analysis is indicative of changes in the MBA market. The Graduate Management Admissions Council’s annual Application Trends Survey Report for 2018 notes that most programmes in the Asia-Pacific, Canada and Europe all saw increases in application volumes this year, while the majority of US programmes declined – possibly as a result of reduced applications from overseas, which Vanderbilt’s Wilkerson blames on tighter immigration policies introduced by the Trump administration, and the consequent restriction on graduates’ opportunity to work in the US post-graduation.

But the change in application trends could also reflect an increasing preference for the one-year MBA programmes typically offered outside the US. The market for these shorter MBAs is much more international: the top five institutions in THE’s analysis are the University of Hong Kong, the Indian School of Business, the Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, the Australia-based S P Jain School of Global Management and Switzerland’s IMD.

Since business school students are older and taking time out of the job market, it is perhaps no surprise that they are eager to put their new-found skills to remunerative use as soon as possible. Andrea Masini, associate dean in charge of the MBA programme at HEC Paris, which is 10th in a ranking of one-year MBAs based on the same criteria as the two-year ranking, explains that his school’s programme actually takes 16 months – a common duration in Europe.

“It’s the perfect compromise with the traditional 24-month US model,” he explains, in terms of the balance between skill acquisition and opportunity cost for the student. “We’ve seen a double-digit increase in the number of applications [for the 16-month courses], which has allowed us to grow the programme and the quality of the programme,” he adds.

Masini says the one-year model is preferred in Europe partly because it distinguishes the continent’s programmes from the US model. But one-year MBAs are not unknown in the US. Lisa Shatz, assistant dean and director of MBA programmes at the University of Texas at Dallas’ Naveen Jindal School of Management, says her institution switched to offering a 16-month course in 1996 because “there was a need in the market”. Millennials want more choice, she explains: “They come in with confidence and want to do things quickly.”

John Fong, CEO and head of campus at the S P Jain School’s Singapore campus, says his institution’s decision to offer one-year courses when it was launched in 2006 arose out of a recognition not only of students’ desire to get a job sooner but also of employers’ desire to “hire our students faster”.

Masini adds that tuition fees for two-year US programmes are considerably higher than for one-year programmes, potentially setting students back $200,000. That could go some way to explaining the gap in scoring for the socio-economic diversity of students on one-year and two-year MBA programmes – with the top two-year programmes faring particularly badly on that score (the metric draws on a survey question about whether the respondent’s parents went to university).

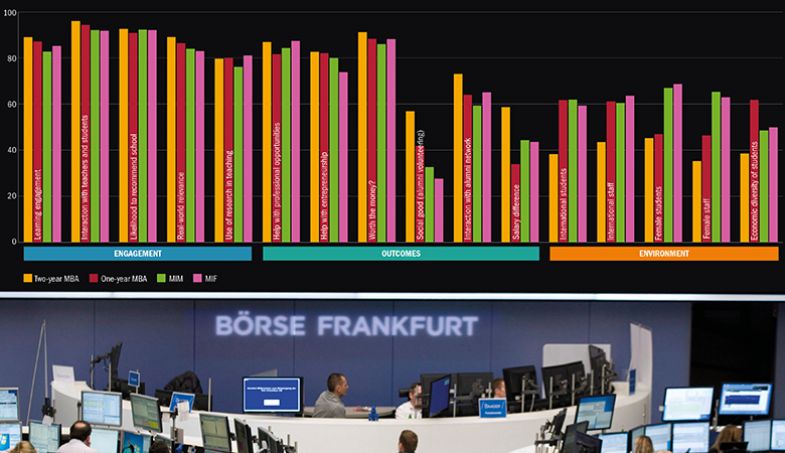

One-year programmes also outperform two-year programmes on internationalisation and representation of women at staff and student levels. However, two-year programmes record higher scores on most other metrics, including the strength of their alumni networks and propensity for their graduates to do voluntary work.

That latter metric is included as a way to probe the extent to which business schools are addressing the claims of critics that they promote an irresponsible, selfish form of capitalism. It is striking that alumni of top two-year programmes are more likely to volunteer than alumni of two-year programmes overall: the reverse of the situation with the alumni of one-year programmes. However, the fact that the two-year list is dominated by US institutions means that some of the differences between one- and two-year programmes could be attributable to national differences, rather than factors inherent to the programmes themselves. In the case of voluntary work, for instance, this is highly valued in the US, and there is arguably more onus placed on successful people – likely to be alumni of the top business schools – to “give something back”.

For all the fame and prestige of MBAs, many business school leaders suggest that a bigger growth area in recent years has been the more recently developed master’s in management (MIM) and master’s in finance (MIF). These typically one-year full-time courses are aimed not at established professionals but at recent graduates who have not yet begun their careers. According to the 2018 GMAC report, there has been recent growth in applications to most MIM and MIF programmes in Europe. And it is on that continent that most such programmes are based – although, according to THE’s analysis, the US programmes tend, again, to be among the most prestigious.

The scores returned by MIM and MIF programmes are broadly similar to those for MBAs. One notable area of discrepancy, again, is volunteering: MIMs and MIFs are much less likely to promote it. However, that could well be because their graduates are at earlier life and career stages than MBA graduates. MIMs and MIFs also have a much higher female representation at staff and student levels, perhaps reflecting the fact that male dominance is less pronounced at more junior corporate levels.

Leila Guerra, associate dean of programmes at Imperial College Business School, which appears in the top five for both MIMs and MIFs, says that although the university has been running these programmes for decades, she has seen an increase in applications in recent years.

“The business school market was once dominated by the MBA, but MIFs and MIMs are now here to stay. Schools that were traditionally MBA-focused are now moving into specialised master’s,” she says.

Despite the resulting increase in competition, Guerra says applications to Imperial’s courses are on the up. “It shows that [MIFs and MIMs] are global brands, and it means the qualifications will be more widely recognised, which is good for us,” she adds. “MIMs and MIFs provide you with a career boost at 22, but if you need to refresh your skills [when you are older] you can come back for an MBA.”

Lynette Ryals, director of Cranfield School of Management, whose MIF ranks sixth, points out that more and more students across the world are pursuing master’s-level study after their undergraduate degrees. And, like Guerra, she emphasises that her business school’s close links to its host institution exposes its students to the most up-to-date research in technology and engineering, which makes them highly employable in those sectors and fulfils the increasing desire of people in their twenties to “build a specialism” early in their careers.

One uncertainty for UK business schools is the impact of Brexit, and the government’s general determination to drive down immigration. HEC Paris’ Masini says that the “Trump and Brexit effect” has already manifested itself in an increase in applications to his school, while the China Europe International Business School’s Ding says that “more and more” talented Indians, Japanese and South Koreans have been applying to his institution.

“Traditionally they go to the US and UK, but now, alongside the growing interest in the Chinese market, there is the perceived risk to career development in these countries, so they come to our school,” he says. “This is a very new trend.”

Guerra says Imperial has yet to feel this effect, but the latest survey from the UK’s Chartered Association of Business Schools found that the majority of UK business schools are extremely worried about Brexit’s effect on their ability to recruit international students (as well as their ability to access European funding for research). And Vanderbilt’s Wilkerson predicts that US schools that have historically relied on international recruitment will find themselves under increasing financial pressure in the coming years.

Bill Boulding, dean and J. B. Fuqua professor of business administration at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, cites further threats to US institutions, in the form of increased international competition, a strong US labour market that decreases workers’ motivation to seek higher qualifications, and questions about value for money as tuition fees for MBAs in particular grow ever higher. Despite this, he “would also consider this to be the golden age of innovation for business education”, as they “adapt to remain relevant for the world we live in today and they meet the challenges that business leaders are facing now – which are very different than in the past”.

“I expect in coming years we’ll continue to see a flight to quality,” he adds. “The schools that are most popular will continue to be the schools that are taking innovation seriously and adapting to the challenges of business today.”

For his part, Stanford’s Feinberg blames the decline in applications to US schools on the global geopolitical forces that shape the business school market, and that have seen some overseas countries – especially China – rise to prominence. “We will continue to see a rise in the quality of management education in developing economies,” he predicts – and, therefore, increased competition for US institutions.

“However, the world of business is becoming more complex, volatile and dynamic and requires more innovative, resilient and compassionate leaders,” he adds. “As long as economic and societal problems persist, business schools that generate such future leaders will not only survive but thrive.”

The universe of master’s: business degrees compared

Top tier: two-year MBA degrees

| Rank 2019 | Institution | Country/region | Resources score | Engagement score | Outcomes score | Environment score | Overall score |

| 1 | Stanford Graduate School of Business | United States | 79.1 | 94.1 | 91 | 40.4 | 82.7 |

| 2 | Cornell University: Johnson | United States | 85.6 | 92.1 | 83.3 | 39.8 | 80.9 |

| 3 | Vanderbilt University: Owen | United States | 85.4 | 93.1 | 89.1 | 18.6 | 80.7 |

| 4 | University of Chicago: Booth | United States | 74.4 | 94.2 | 86.9 | 37 | 79.6 |

| 5 | Duke University: Fuqua | United States | 71.5 | 92.7 | 85 | 34.1 | 77.5 |

| =6 | University of Virginia: Darden | United States | 67.1 | 93.5 | 88.6 | 28.7 | 77.3 |

| =6 | Yale School of Management | United States | 67.1 | 93 | 85.1 | 40.9 | 77.3 |

| 8 | Carnegie Mellon: Tepper | United States | 73.3 | 91.9 | 77.9 | 26.7 | 74.1 |

| 9 | Purdue University: Krannert | United States | 53.1 | 89.8 | 82.2 | 54.7 | 73.5 |

| =10 | China Europe International Business School (CEIBS) | China | 67.5 | 86.9 | 76.7 | 45.7 | 73.2 |

| =10 | University of Michigan: Ross | United States | 55.4 | 93.3 | 85.1 | 31.2 | 73.2 |

See the full results

Top tier: one-year MBA degrees

| Rank 2019 | Institution | Country/region | Resources score | Engagement score | Outcomes score | Environment score | Overall score |

| 1 | University of Hong Kong | Hong Kong | 51.2 | 88.5 | 80.9 | 87.5 | 76.2 |

| 2 | Indian School of Business | India | 78.4 | 90.8 | 83.4 | 14 | 75.7 |

| 3 | Indian Institute of Management Calcutta | India | 76.3 | 89 | 85 | 15.7 | 75.5 |

| 4 | S P Jain School of Global Management | Australia | 76 | 84.4 | 71.6 | 62.9 | 74.8 |

| 5 | IMD | Switzerland | 50.2 | 93.1 | 83.4 | 52.4 | 73.8 |

| 6 | Western University: Ivey | Canada | 93.4 | 90 | 59.3 | 42.3 | 73.4 |

| 7 | Cranfield School of Management | United Kingdom | 67.6 | 93.3 | 60 | 63.7 | 70.7 |

| 8 | Melbourne Business School | Australia | 61.7 | 88.4 | 66.7 | 49.2 | 68.8 |

| 9 | NUS Business School | Singapore | 48.7 | 85.4 | 69.9 | 71.8 | 68.7 |

| 10 | HEC Paris | France | 54.9 | 88.9 | 65.5 | 59 | 67.9 |

See the full results

Top tier: master’s in management

| Rank 2019 | Institution | Country/region | Resources score | Engagement score | Outcomes score | Environment score | Overall score |

| 1 | Thunderbird School of Global Management | United States | 83.3 | 89.4 | 84.9 | 40.7 | 80.3 |

| 2 | HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management | Germany | 53.6 | 92.4 | 86.3 | 41.4 | 74.3 |

| 3 | WHU: Beisheim | Germany | 57.4 | 92.5 | 86.8 | 29.2 | 74 |

| 4 | Eada Business School Barcelona | Spain | 54.3 | 91 | 70.7 | 73.2 | 72 |

| 5 | Imperial College Business School | United Kingdom | 58.3 | 87.7 | 62.1 | 69.4 | 68.4 |

| =6 | University of Mannheim Business School | Germany | 48.6 | 86.7 | 74.1 | 46 | 67.5 |

| =6 | Wake Forest University School of Business | United States | 51.1 | 88.1 | 78.3 | 24.8 | 67.5 |

| 8 | IQS School of Management | Spain | 51.8 | 88.8 | 70.8 | 42.8 | 67.2 |

| =9 | ESSEC Business School | France | 49.3 | 87.2 | 67.9 | 59.8 | 67.1 |

| =9 | Maastricht University School of Business and Economics | Netherlands | 46.4 | 88.7 | 65 | 71.9 | 67.1 |

See the full results

Top tier: master’s in finance

| Rank 2019 | Institution | Country/region | Resources score | Engagement score | Outcomes score | Environment score | Overall score |

| 1 | Vanderbilt University: Owen | United States | 86.2 | 92.7 | 88.5 | 15.5 | 80.2 |

| 2 | Washington University in St Louis: Olin | United States | 55.4 | 89.4 | 79.3 | 36.7 | 70.8 |

| 3 | Eada Business School Barcelona | Spain | 54.1 | 89 | 69.9 | 67.4 | 70.4 |

| 4 | ESIC Business and Marketing School | Spain | 72.2 | 85.2 | 64.5 | 40.9 | 68.8 |

| 5 | Imperial College Business School | United Kingdom | 59 | 88.6 | 60.7 | 72.8 | 68.7 |

| 6 | Cranfield School of Management | United Kingdom | 65.5 | 86.3 | 62.9 | 53.2 | 68.3 |

| 7 | Purdue University: Krannert | United States | 51.9 | 89.3 | 70.6 | 48.9 | 68 |

| 8 | Tulane University: Freeman | United States | 49.3 | 90.6 | 70.8 | 47.5 | 67.6 |

| 9 | City, University of London: Cass | United Kingdom | 51.9 | 88.4 | 62.8 | 68.8 | 67.2 |

| 10 | Nottingham University Business School | United Kingdom | 51.1 | 88.2 | 65.9 | 60.3 | 67.1 |