I saw women come to the campus in burkas, take them off and hang them on a peg. They filled the space with colour and sound and confidence

When Mursal Hamraz finished secondary school in her native Afghanistan, she had just one option to further her education: taking up an offer of a place at a public university to study for a fine arts degree, which was not of interest to her.

Six months later, her father told her of a new private university in Bangladesh that would provide her with a full scholarship.

“My dad is really supportive of my education, which is an exception in Afghanistan,” Hamraz says. “Most fathers don’t want their daughters to go to university or even to do jobs.”

But it was other women in her mother’s rural home town who sounded the loudest protests about the idea of studying abroad.

“I faced different reactions,” Hamraz says. “Some women appreciated it and some other women had the idea that, no, girls can’t go abroad and get an education.”

When she told them that the university admitted only women, however, she says, “that gave them a little bit of comfort”.

Hamraz attended the Asian University for Women in the port city of Chittagong, which opened in 2008. Today, its 500-strong student cohort comes from Afghanistan, Bhutan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Burma, Pakistan, Palestine, Syria and eight other countries where women face restricted opportunities for education because of politics, religion, caste or culture.

“We tended to empower each other by telling each other you can do anything,” says Hamraz, who is now one of 10 women working in the 100-employee Kabul office of the Afghan Ministry of Counter Narcotics.

As for those sceptical women in her mother’s home town, Hamraz says, “Education is the only way to open their eyes and make them realise that they can do the same things as men.”

All-female higher education worldwide has come to a divide: in the West, where women have unfettered access to co-educational institutions – and, among the student body, outnumber men at many of them – women-only universities are closing and enrolment is largely declining. But in many developing countries, new all-female campuses are opening and expanding, and enrolment is soaring.

“Maybe women’s colleges have become anachronistic in the West, but what you see in Asia is that they have all the force that you can think of – intellectual force, force for social change,” says Kamal Ahmad, founder of the Asian University for Women, which is housed, for now, in a converted apartment building while a new campus is being built, underwritten largely by British, American and other international donors.

He adds: “It may have to do with the situation of women at large. They are at the margins of society in these countries. The yearning for education is so much greater, and the passion for change.”

But if there is a split in the direction of single-gender institutions for women in the East and West, they also have a paradox in common: single-sex universities give women the tools they need to help reverse the cultural forces that put them there in the first place.

“Irony has always been very good for women,” says Ana Martínez-Alemán, who chairs the educational leadership and higher education department at Boston College, and who studies the impact of culture and gender on teaching.

“Born of discrimination and the isolation of women in certain sectors, these institutions then give them a toehold. Their graduates become pioneers, and that’s how the pragmatic ball starts rolling,” she says.

In the West, that momentum has reached a point where few women now see the need for single-sex higher education. In the US, for example, only one in 20 women now even considers applying to an all-female university, according to the Women’s College Coalition.

“Once women had access to what were formerly men’s institutions, they began to enrol in them,” says Kristen Renn, a professor of education at Michigan State University and author of the recently published book Women’s Colleges and Universities in a Global Context. “Young women now believe the playing field is more than level.”

And Western women-only institutions – many of which are liberal arts colleges – are contending with the same pressures facing co-educational universities that focus on the liberal arts, which are out of fashion at a time when students want to study those subjects offering the skills that they think they need to secure well-paying jobs.

In the past 50 years, the number of all-female institutions has plummeted from 230 in the US to 46 – and, with Chatham University in Pittsburgh planning to admit men to its undergraduate college from next year, will soon shrink to 45. In Canada the number has fallen from three to one, and in the UK from 10 to four (three Cambridge colleges and a specialist college in Surbiton remain all-female). Overall enrolment in the US has risen by a third since 2000, but at women-only universities it has fallen during that time by 29 per cent.

By contrast, the all-female Princess Nora bint Abdulrahman University in Riyadh, which was created in 2004 as Riyadh University for Women out of six all-female universities in the city and renamed in 2008, has grown to 52,000 students. It is now the largest women-only university in the world. Lady Shri Ram College for Women in New Delhi this year had 120,000 applicants for 600 places, the institution says, a level of competitiveness that makes it 12 times more selective than Harvard.

Some of those numbers are the result of the sheer demand for, and scant supply of, quality higher education of any sort in fast-growing countries such as India. But many students who choose all-female institutions “come as very, very shy and docile, struggling with families who are still not convinced that girls need a higher education”, says Deepika Papneja, a member of staff at Lady Shri Ram who teaches gender studies and the sociology of education. “Their families feel more safe if the girls are attending an all-women’s institution.”

These students and other women, however, says Papneja, who is a Lady Shri Ram alumna, “are demanding more education, more quality education”. And all-female institutions provide them with “liberating, democratic spaces where they can do something different – where they can change the way society looks at women”.

In a region where there continues to be not only discrimination but also much public concern about the levels of violence against women, Papneja says: “I don’t think we’ve reached a point where we can be complacent. The world has not really changed to an extent that we can start talking about equality. There has been change, and a lot of change, but there still is a very, very long way to go. We still need, especially for at least the next couple of decades, spaces like Lady Shri Ram, where women find a voice and realise that they are individuals in their own right and have the right to do what they want to do and the means to do what they want to do.”

It’s not just a moral imperative. Developing economies are hungry for educated workers, including more women with university degrees, “given that they will be X per cent of the probable workforce in whatever country we’re talking about”, says Martínez-Alemán.

Yet some women-only universities emphasise traditional “female careers” such as teaching, social work and nursing, perpetuating rather than reducing inequality, Ahmad and others note.

“Many women’s colleges tend to reinforce the traditional values of society,” he says. “They’re teaching home economics and other things that reinforce the old value structure.”

Even for women who graduate from fast-expanding women’s institutions such as Princess Nora bint Abdulrahman University, “it’s not clear to me what their next step is,” Renn says. “I mean, they still can’t drive cars.”

But many women’s universities are trying to do what their Western counterparts helped to do: reverse these limitations. The Asian University for Women, for example, purposely seeks out women from places where they have the fewest opportunities, and gives most of them full scholarships. It offers them a one-year programme called the Access Academy, which provides instruction in English, mathematics, world history, geography, computer literacy and other subjects that girls from those disadvantaged areas often aren’t taught sufficiently well in primary and secondary schools. Many students also undertake coveted internships at the World Bank, HSBC, Democracy International, the Tata group and other companies and organisations.

“South Asia has a history of women political leaders in virtually every country, but invariably those political leaders, however successful they may have been, rode on the mantle of a family member, whether it was a father or a late husband,” Ahmad says. “We want to shift that issue of women’s leadership to being based on merit or talent. We think that if we can create an emerging network of young women leaders who have the social commitment and the education to run with it, that can make all the difference.”

But it isn’t easy, he adds. “Women’s education remains a hugely contested matter, not just in societies like Afghanistan and Pakistan, but even in more liberal societies,” Ahmad says. “Even in India and Bangladesh, there are struggles that happen within families when a young woman finally says that she wants to go off to college. So at an abstract level you might say that society in general has progressed to such a degree that separate institutions might not have meaning, but what we find is that that’s not the case. In fact, we were surprised by the degree to which it’s not the case.”

When they graduate, however, says Papneja, “every woman who comes out of this place [Lady Shri Ram] is truly prepared to take on the world”. And the fact that all-female institutions in developing nations are thriving, she says, “is because women do feel that it’s important that such spaces are protected”.

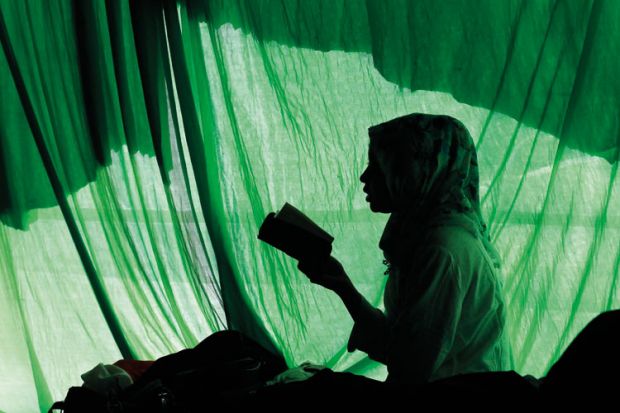

Renn visited 13 campuses in 10 countries on five continents to conduct research for her book. At one institution in India she saw women “come to the campus in burkas, take them off and hang them on a peg. They instantly filled the space with colour and sound and confidence, and that’s their life for three years, for eight hours a day, in this place where they’re free to live and laugh and learn and fill up the space. That’s got to change them.”

Meanwhile, in Western countries some all-female universities are responding to their enrolment challenges by reaching out to immigrants whose cultures frown on mixing the sexes.

“Women’s colleges are starting to tap into communities that have not put their foot in the door yet,” says Colleen Hanycz, the principal of Brescia University College in Ontario, Canada’s only all-female institution.

They are also pushing the idea of empowerment, even in cultures where women face much less discrimination, but where research shows they earn less money than men for the same jobs, and are often less likely to be hired. In higher education, as in other sectors, there also remains a yawning gender gap in senior posts. (Just 17 per cent of vice-chancellors in the UK are women.)

“There is still hidden bias based on gender,” says Lynn Pasquerella, the president of Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. Her university is the oldest continuously operated all-female institution in the US and one of the elite so-called Seven Sisters, a group of East Coast liberal arts colleges for women, which in 2003 helped establish an international networking and support organisation called Women’s Education Worldwide.

“Here it’s not an issue, because every leadership role is held by a woman. There is an expectation that when you leave, you will lead,” Pasquerella adds. Renn argues that women’s colleges and universities are “counter-cultural organisations” wherever they are.

But some day all-female institutions in developing countries may begin to work themselves out of a purpose, just as they’ve begun to do in the West, some suggest.

“It’s conjecture,” says Martínez-Alemán. “But if we were to return to this question 50 years from now, would we see the same things happen there?”

Newnham College, Cambridge: a place to take risks, not a hiding place

In the West, many women’s colleges were established in the 19th century, when women were still largely excluded from mainstream higher education.

But as more and more all-male institutions opened their doors to women, that initial rationale melted away, and many women’s colleges have also become co-educational.

In the UK, the University of Cambridge’s Girton College began admitting men in 1976 and the University of Oxford’s St Hilda’s did likewise in 2008. At Cambridge, however, Newnham, Murray Edwards and Lucy Cavendish colleges have remained women-only.

According to Dame Carol Black (above), principal of Newnham, her institution – founded in 1871 by Trinity College philosopher Henry Sidgwick – has no plans to change its policy on admitting only female students and fellows.

One reason is that, unlike women-only liberal arts colleges in the US such as Wellesley, Smith and Mount Holyoke, Newnham is home to students who are largely educated in the co-educational environment of the wider university. Nor is the college a “nunnery”, from which students’ male friends, or male tutors, are barred.

Dame Carol believes that the justification for all-female institutions in the West resides in essence in student demand for them. And while that demand has flagged at some colleges over the years – accelerating the shift towards mixed-sex admissions in the West – several of the most prominent US institutions are riding the crest of a recruitment wave after “rebranding” exercises that saw them talk up the “added value” they can bring to women’s education, in terms of boosting their confidence and preparing them for successful careers.

Newnham also runs programmes – open to women across the university – aimed at boosting confidence and encouraging women to “really aspire” and “make the most of themselves” by improving their networking skills and willingness to take risks, she says.

“I am particularly keen that they learn risk-taking and leadership skills. An all-female college gives them that opportunity because they have to chair everything and develop everything we do.”

And although few students choose Newnham specifically because of these programmes – not least because women enter Cambridge as men’s academic equals and often aren’t aware at that stage that they lack confidence – they find them “one of the most attractive things about us” when they get there, Dame Carol says.

The admissions and finances of Newnham remain stable. Nonetheless, the college is currently immersed in some soul-searching about how to better project itself.

“We shouldn’t be so reticent about saying we are a women-only college,” Dame Carol says. “It is almost as if people felt there was something bad about it – as if women-only colleges were quirks of nature.”

She also feels that all-female colleges could play a greater role in advocating for women’s education globally, and perhaps even speak out more generally on women’s issues, although she admits this would be “more controversial”.

But one thing women’s colleges should not be thought of, Dame Carol argues, is “havens”.

“I don’t think most women’s colleges would want to be thought of as just somewhere you retreat to from the fray,” she says. “We like to think we are warm and nurturing, but we are not a hiding place. That is something very different.”

Paul Jump