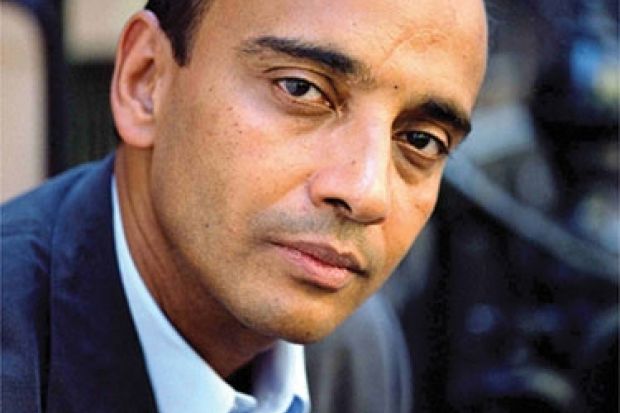

When Kwame Anthony Appiah left home to go to the University of Cambridge, the last thing his Ghanaian father said to him - in complete seriousness - was "don't dishonour the family name". It was not the kind of advice he would ever have got from the English side of his family.

One of the reasons he became a philosopher, he now believes, is that his mixed background left him caught between "different ways of doing things"; this situation forced him at an early age to "consider whether there were any arguments for them or whether they were just matters of convention".

Notions of "honour" obviously vary from culture to culture, and some seem to function largely as fig leaves for covering up cruelty and injustice. Take the case of a disabled Pakistani girl who was put to death in 1999 for "dishonouring" her community - because she had been raped. If such acts are committed in the name of honour, shouldn't the very word be dumped for being well past its sell-by date?

That, Appiah argues, would be a great mistake.

"It sounds archaic and possibly even reactionary to be interested in honour," he admits, "because there's a side of honour associated with undemocratic and hierarchical things. One of the projects of my new book is to democratise honour...Honour can be part of the social mechanism by which we get people to do the right thing."

His book The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen makes this case - and draws out lessons for today - by exploring how changing notions of honour put an end to three major injustices: duelling among the British aristocracy, foot binding in China and the Atlantic slave trade.

It was never just a question of making a convincing argument. All these abuses were widely agreed to be wrong long before effective movements arose to eliminate them, so the real question is how pressures for reform acquired an irresistible momentum and overturned long-entrenched institutions. Yet to reconstruct such "moral revolutions" requires a degree of understanding of how people came to be doing terrible things in the first place. It is here that Appiah can draw on his highly unusual upbringing.

He is now Laurance S. Rockefeller university professor of philosophy at Princeton University and has written a number of celebrated books, including In My Father's House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture (1992), The Ethics of Identity (2005) and Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers (2006), as well as a series of detective novels.

On his 21st birthday, he made a careful calculation and realised that he'd spent almost exactly the same amount of time in Ghana and in England.

"I grew up in Kumasi, the capital of an old empire," he recalls, "and there was still a king sitting in the palace up the hill. I went there quite often because he was married to my great-aunt. In 1970, he was succeeded by someone who was married to my aunt, so my father, mother and I spent quite a lot of time hanging around there. He was my favourite uncle beforehand, although I didn't see so much of him after he became king."

To balance the Ghanaian royalty on one side of the family, Appiah is also the son of children's writer Peggy Cripps and the grandson of Sir Stafford Cripps, a Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, and he was sent to a progressive English boarding school. This meant that he had other relatives who were "old-fashioned gentlemen" and even a great-uncle who sported a monocle.

Duelling was a defining element of the gentlemanly code of honour for several centuries. Yet in 1829, when the Duke of Wellington fought a famous duel that Appiah describes in his book, critics were beginning to say he had only made himself look ridiculous. By 1851, when Sir William Gregory was willing to fight because of "a rather complicated dispute over the concealment of the ownership of a horse", the institution seemed patently absurd. Even Sir William's second was heard to wonder "whether death is the appropriate penalty for lying about a horse".

If Appiah has a certain first-hand knowledge of latter-day English gentlemen, he also has some surprising links with the world of slavery.

"I like to remind my students that I have slavers on both sides of my family," he explains cheerfully. "The kingdom I grew up in was at the height of its growth when it was a central participant in the slave trade. Slavery was abolished in the colonial Gold Coast not long after my father was born, but there were people around us who were the children of slaves and were thought about in a way that reflected their former status. My father once told me off when I asked whether an 'auntie' was related to us, since she was a descendant of the family slave and that couldn't be said in public.

"So slavery was there, even though we didn't talk about it, even though the words weren't used - but shades of it were there all around us. In the US, too, legacies of slavery, of a rather different sort, are everywhere."

It is this distinction, reflects Appiah, that has led to "a long and interesting tradition of difficulties between Africans from Africa and African-Americans. The former tend to have different feelings about white people, for a start, who didn't enslave them but to whom they may have sold slaves. It's a different kind of relationship!

"I have to accept honour responsibilities for the doings of my ancestors - that includes some admirable stuff and some stuff that's pretty shameful. But I can't repudiate it; I can't make them not my ancestors."

So how can honour be steered to undermine rather than prop up injustice? British workers in the 19th century were often racist but came to oppose plantation slavery because the institution implied that there was something degrading about hard physical labour, which offended their own sense of dignity and identity. Foot binding disappeared over the course of a few decades as outsiders such as Protestant missionaries, the wives of businessmen and other elite expatriate women convinced the Chinese that it was a blot on their national honour.

Such parallels, in Appiah's view, can help us develop strategies for dealing with contemporary problems. When it comes to "honour killings", he reminds us, "you have to consider how deeply embedded these things are - they are older than Islam and were practised in Mediterranean Christian cultures well into the 20th century. Faced with the killing of women, one's natural reaction is to use moral exhortation to get people to give it up. But I don't think that's a strategy that will work, because honour is part of human psychology and can align itself very strongly against morality.

"What will work, I believe, is shifting honour to pull in the opposite direction. A Pakistani human rights lawyer asked absolutely the right question: what kind of honour is it to kill an unarmed woman? She took one feature of the existing structure of honour - honourable men protect women and their family - and noticed its tension with the practice and suggested where a more consistent form of honour would lead," Appiah says.

"Together with wider shifts towards a more gender-egalitarian society, what may help effect change is a set of activists working to get people to recognise that their idea of 'honour' is essentially dishonourable."