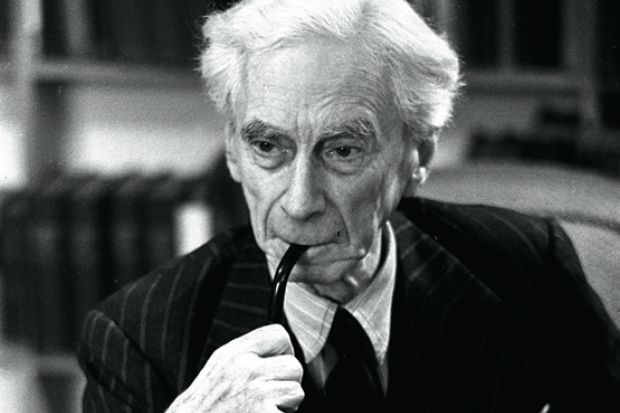

Bertrand Russell: The First Media Academic

BBC Radio 4, 14 January, 8.00pm-9.00pm

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) was not only "a mathematician and a philosopher, an earl and an atheist, a peace campaigner and a moral reformer", argues presenter Robin Ince, but also "the first intellectual star of the modern media age". Yet, unlike most of this breed, "his appearances were backed up by a depth of knowledge and understanding, a charm and compassion, that makes him as relevant today as he was 40 years ago".

Ince's programme makes an energetic case for Russell's continuing importance. He was in many ways a surprising star. Shy and self-conscious about public speaking in his youth, he had a forbidding reputation as a philosopher and was already 50 when the BBC was founded as the British Broadcasting Company in 1922. Yet he took to radio with great enthusiasm and became so well known a public figure that Jonathan Miller could mercilessly mock his voice and manner in the satirical revue Beyond the Fringe. Close to 40 years after his death, Russell could still appear as the hero of Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos Papadimitriou's graphic novel Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth.

Two of today's leading "media academics", Marcus du Sautoy and Brian Cox, pay tribute to Russell as a pioneer with real intellectual clout. Material from the archives reveals his impact on earlier generations. Former Labour leader Michael Foot, for example, called Russell "unquestionably my man of the century" and almost "the happiest man I ever saw", although this happiness had been "achieved against enormous odds".

In the midst of this love-in, the extracts from Russell's actual broadcasts tell a rather different story. Far too often he seems to fall into a kind of self-conscious "fine writing" style that has worn pretty badly and can get suspiciously close to windy grandiosity. "The world of mathematics and logic", he once told listeners, "remains in its own domain delightful, but it is a domain of the imagination. Mathematics must live with music and poetry within the region of man-made beauty, not amid the dust and grime of the world."

In a splendid epigram cited by Ince, Russell once said that "the idiots are cock-sure, the intelligent are full of doubt". But although his broadcasts are good at adopting a tone of sweet reasonableness, he seems to have suffered very little from self-doubt. On one level, of course, he was admirably willing to engage with "the dust and grime of the world", and was even arrested at the age of 89 for protesting against nuclear weapons. Yet there is something deeply irritating about the faux-naivety of the interviews he gave at the time, as if he were the only person to realise that "continual progress in knowledge, happiness and wisdom" was preferable to "universal death" or that "the extermination of the human race" would be "rather a pity".