One of the key political debates of the past decade in much of the developed world has been whether regional inequality within countries – particularly between major cities and a nation’s hinterlands – has grown to an unsustainable level.

It has driven much of the political language in the UK, for instance, with the Westminster government’s “levelling-up” mantra recently finally taking the shape of an official policy paper, and in the US, where urban-rural divides have featured prominently in public discourse since Donald Trump’s 2016 election to the presidency. Higher education has also been central to these debates, with political fault lines often being seen to align with educational attainment.

But what do the available international data on higher education actually show when it comes to regional divides? Are there examples where countries have achieved more regional equality than others in terms of educational attainment? And what should be done to improve the picture in less equal national landscapes?

The most recent edition of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s annual Education at a Glance dataset suggests that the tendency for major cities to have higher concentrations of graduates is common across most countries.

In all but four of 34 OECD and “partner” countries with available data, the region around a capital city has the highest share of the adult population educated to at least tertiary level.

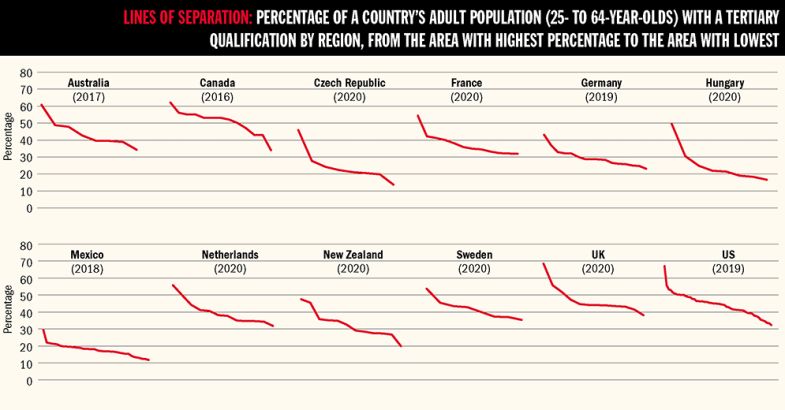

But there are a number of countries where the gap between the areas with the highest and the lowest shares of people who have gained a tertiary qualification is very wide – more than 30 percentage points in some cases.

Examples include the US – where the tertiary attainment rate ranges from 32 per cent in one state (West Virginia) up to 67 per cent in Washington DC – the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Russia and the UK.

In other nations, the gap appears to be much smaller. Among anglophone nations, Canada and Australia have smaller overall gaps than the UK and the US. In continental Europe, France, Germany and the Netherlands all have differences closer to 20 percentage points. Some Scandinavian countries such as Sweden and, particularly, Finland, fall below even this.

The data depend very much on the number of regions in a country, and they can be skewed by comparing regions with heavily populated areas with ones that are sparsely populated. For example, in Canada the region with the lowest share of tertiary-educated adults is Nunavut, whose population is below 30,000. A capital city region with a very large graduate cohort, such as London or Washington DC, can also make the gap much bigger than it otherwise might be.

But regional inequality in terms of attainment – whether that is the result of a disparity in provision or the migration of graduates, or both – is clear from the data, and it also appears that some countries have been more successful at preventing the gap from becoming a gulf.

Mitigating such disparities was important for reasons of both “social justice” and “economic efficiency”, said Jamil Salmi, former coordinator of the World Bank’s tertiary education programme and emeritus professor of higher education policy at Chile’s Diego Portales University.

Nations that had “achieved better results” in terms of this mitigation “have several features” in common, Professor Salmi said. “First, they offer good quality primary and secondary education everywhere,” he said, citing examples such as Finland and South Korea. “Second, they try to distribute good quality higher education institutions across all regions, which helps to reach marginal groups…who would otherwise find it difficult to send their children to study in remote cities.”

Ellen Hazelkorn, founding partner of BH Associates education consultants and emeritus professor in higher education policy at Technological University Dublin, said setting up sufficient provision in less populated areas clearly had its challenges, given that a critical mass of students and staff was needed to make an institution “viable”.

But countries have taken innovative approaches to get around such difficulties, she said, citing Finland as an example.

“The Finns have spent a lot of time trying to set up not just regional universities but regional hubs where you’ve got different universities sharing common facilities,” she pointed out.

Stephen Gavazzi, professor of human development and family science at Ohio State University, who has explored the educational and political urban-rural divide in the context of US public universities, said sometimes having a physical presence everywhere was “impractical”.

In this case, he said, “serving rural and urban communities equally may be more easily accomplished by ensuring proportional representation of students from all geographic areas, coupled with outreach and engagement activities that target communities across the rural-urban spectrum”.

Professor Hazelkorn stressed that another key consideration when looking at regional provision was whether students were able to access education of the same quality wherever they were.

Simply considering where universities were located in Europe appears to show an even geographical spread, she said. However, “what you don’t have is these institutions being given the same level of attention, the same level of status…and that is a real problem”.

This was where concentration of funding and resources, often determined by metrics that stressed success in the international arena, might be a problem.

If “your measures of success are contrary to what you’re trying to achieve” locally, then you might need indicators that “influence your direction of travel”, such as research collaboration with local small businesses, for instance, she said.

This also demonstrated why reducing regional inequalities also relied on higher education policy being integrated with a host of other areas, including, but not limited to, boosting innovation, skills, small businesses and transport infrastructure, she said. Without such coordination and support, even if students can access good local higher education provision, they might still leave the region when they graduate.

Graeme Atherton, head of the Centre for Inequality and Levelling Up at the University of West London, said the natural extension of this was that regions also needed to be given the power to control how they shaped these policies.

“Economic investment is essential if graduate-level opportunities are to be created. Devolution of power matters in order to ensure that investment works – or at least heighten the chances of it working – in the context of that place, so that it fits with the strengths and weaknesses of the place.

“It is much harder to ensure that this investment is successful without good local leadership.”

But national higher education policies can be important, too.

Professor Salmi said financial aid for students “was indispensable to overcome the economic barriers faced by students from disadvantaged groups in rural and remote areas”.

“Some governments, for example Australia, have also offered financial incentives to higher education institutions, through the funding allocation formula or special grant programmes, to put in place outreach and retention programmes to increase access and success for traditionally under-represented groups,” he said.

后记

Print headline: Graduate gap: which nations are least equal in HE access?