Mapping out the carbon emissions of a single university is no easy feat, let alone trying to get a picture of the impact of the whole sector.

Institutions are complex beasts, so while many may know the energy usage of their buildings, for example, measuring the commutes of their staff and students – or the carbon used in research projects – is often less well understood.

As global attention turns to the battle to reach net zero by 2050 – and avert the worst of the environmental damage human beings are causing – universities and colleges are uniquely placed to harness their knowledge and influence to make a difference.

This was the belief of the Royal Anniversary Trust in the UK, which set 21 of its most recent prizewinners – all higher and further education institutions – a challenge to look at how to accelerate the sector’s own path to net zero.

“We’ve got globally leading academics in the carbon reduction space [and] some of the most interesting research and on-the-ground projects going on anywhere,” said the chief executive of the trust, Kristina Murrin.

“We wanted to set out and try to amplify those and share best practice. But also ask what is it that could free that up and accelerate it and what could we ask government to do to support this progress?”

The resulting report represents some of the most comprehensive work to date on what the sector’s carbon footprint actually looks like and how a road map could be established for how to reduce it.

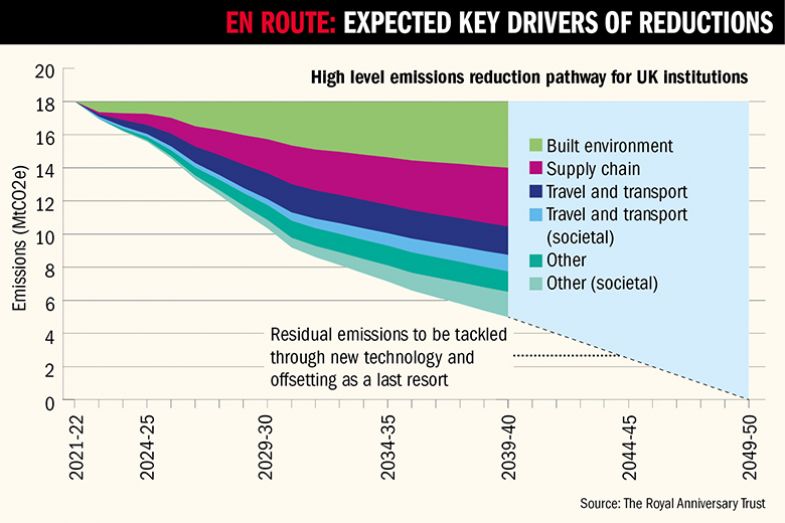

Carbon consultancy firm EcoAct has developed a rough “reduction pathway model” that showed – using initial estimates – how improvements across the built environment, supply chains and travel and transport could reduce emissions by 72 per cent, with the sector encouraged to think about ways it could make up the further 28 per cent needed.

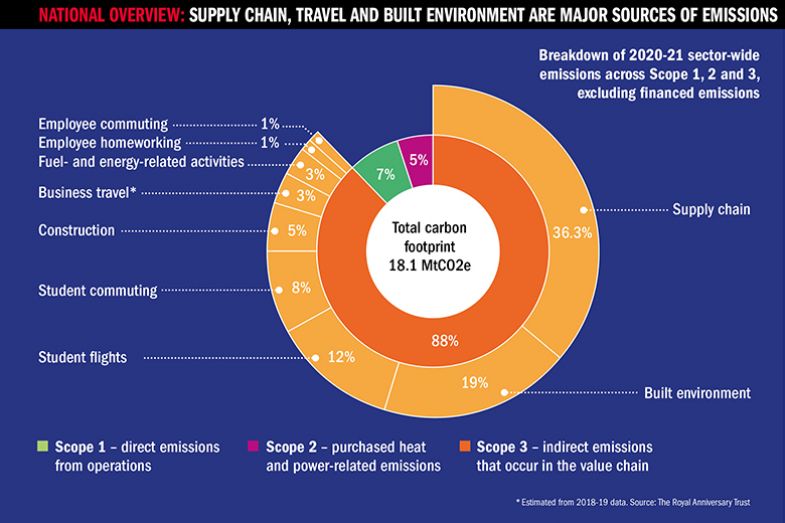

Currently, the carbon footprint for the whole tertiary education sector is 18.1 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e), according to EcoAct, which estimated that it would be almost triple this figure if institutions’ pensions and investments were included. Of the total, higher education institutions were responsible for 86 per cent, about 6.3 tCO2e per student.

The built environment caused 19 per cent of the emissions, while travel and transport was slightly higher at 24 per cent. By far the biggest contributor was emissions embedded in the supply chain, which was much more of an issue than had been anticipated, according to Ms Murrin, a former policy adviser in 10 Downing Street.

Penny Baxter, director of sustainability consultancy SB+CO, who worked on the project, said this was one of the toughest challenges for institutions trying to get to grips with their footprint, and she sensed a “real reluctance” to face up to it.

“There was an awareness of the importance of the supply chain,” she said. “But it was being pushed down the road by institutions who felt the focus should be on their own operations, their buildings and physical footprint. Whereas if you look at the private sector, there is more of a recognition that if everyone moves together, then everyone’s emissions reduce.”

Given the scale of the sector’s spend in local communities, Ms Baxter said, this was a “massive opportunity” to use its influence to drive down emissions.

One of the main recommendations of the report is, therefore, for the Westminster government to create an online portal that brings together existing data from carbon reporting requirements so universities can get a better idea of the emissions of the companies they work with. This should be combined with efforts to increase “carbon literacy” within small businesses, the report says.

The report also recommends the creation of a scheme that encourages graduates to lend their expertise in sustainability to the sector for a limited time, similar to the model developed by Teach First, under which graduates teach in schools before moving on to jobs in other industries.

“There is a huge lack of skills in this area nationally. A lot of people are being sucked into the private sector on very high wages,” said Ms Murrin. “Is there a scheme the government could come up with that looks at whether we could take some of these graduates who have been trained in carbon assessing, for example, and encourage them to go into the tertiary education sector for a period?”

Funders such as UK Research and Innovation should also ensure that reporting on carbon emissions – and how they will be mitigated – becomes part of funding bids, the report states.

Ms Murrin said she felt the sector would welcome further regulation in this area, even if it came with more administration.

Without carbon reduction targets being embedded in areas such as research and governance, it was all too easy for environmental concerns to get lost when faced with more short-term aims such as saving money, according to Ms Baxter.

“At the top of the university, if there isn’t a check and balance for a carbon impact of a decision, then those things can get kicked out really easily before anyone understands this would mean they will miss their net zero target,” she said.

Ms Baxter said she was conscious that when people see, for example, the 12 per cent of emissions that come from student flights, it could be used as further firepower for restricting international student numbers.

But, she said, the message of the report is that innovation is needed, and the sector should look at where behaviour can change, and emissions can be saved, without totally disrupting its business model. So, for example, campuses could be made more welcoming year-round to those from abroad, so students do not feel the need to fly home during every holiday.

Collaboration on many of these issues has sometimes been held back by the competitive nature of the sector, Ms Baxter believed, especially as sustainability is now a key factor for students when deciding where to study.

The report recommends that the government fund mechanisms that would allow higher education and further education institutions in the same area to band together on initiatives such as investing in renewable technologies or applying for grants. A hub to support those conversations and the sharing of best practice is also sorely needed.

“One of the most striking things for us at the beginning of the project was this was almost the first time, not only that HE and FE had come together, but it was also the first time academics were talking properly with their professional services colleagues – those running estates, the people responsible for strategy,” Ms Baxter said.

“Academics had incredible insight on the climate agenda but were perhaps not contributing to what they were doing as an institute and the steps needed internally.”

Ms Murrin said the different expertise and focuses of HE and FE could be “very mutually supportive of each other”.

“Universities have the research capacities and specialist teams working on this, and FE has the supply of skills and technical abilities as well as a huge number of students,” she said.

Hope is sometimes hard to find in the global challenge of reducing carbon emissions, where the scale of the issue often dwarfs any sense that progress is being made. But Ms Murrin said the project had left her feeling “massively positive”.

“When you see the sector in operation, discussing, looking at an issue, coming up with solutions, they are really impressive. We really do have the best academics and institutions globally; you can feel that.

“There are lots of things we can do, and they are doable. You look at some issues and you think, I can’t see how we could make progress, but there is lots we can do in this space. This has given us a blueprint for how to do that.”