During the UK launch of this year’s Education at a Glance report, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s director for education and skills, Andreas Schleicher, pointed to one possible by-product of the country’s high fees for international students.

“One of the consequences”, he said, was that “very few people from low- and middle-income countries can afford studying in the UK”.

“In the US, for example, if you are really talented, you do get scholarships wherever you come from, whereas [in the UK] the entrance fee is very, very high.”

Data presented by Mr Schleicher to back up his point showed that about 14.5 per cent of the UK’s international students in 2019 were from low-income or lower-middle-income countries, as classed by the World Bank, compared with 26.4 per cent in the US, 41 per cent in Australia, 42 per cent in Canada and 55 per cent in France.

But do these figures tell the whole story? Does enrolling large numbers of students from such countries always mean you are reaching the poorest? And although there may be a benefit to individuals, could such recruitment be damaging to the developing countries themselves?

Before assessing such questions, one key point to note is that removing lower-middle-income nations – which include some major markets for international students such as India and Nigeria – from such an analysis already alters the picture.

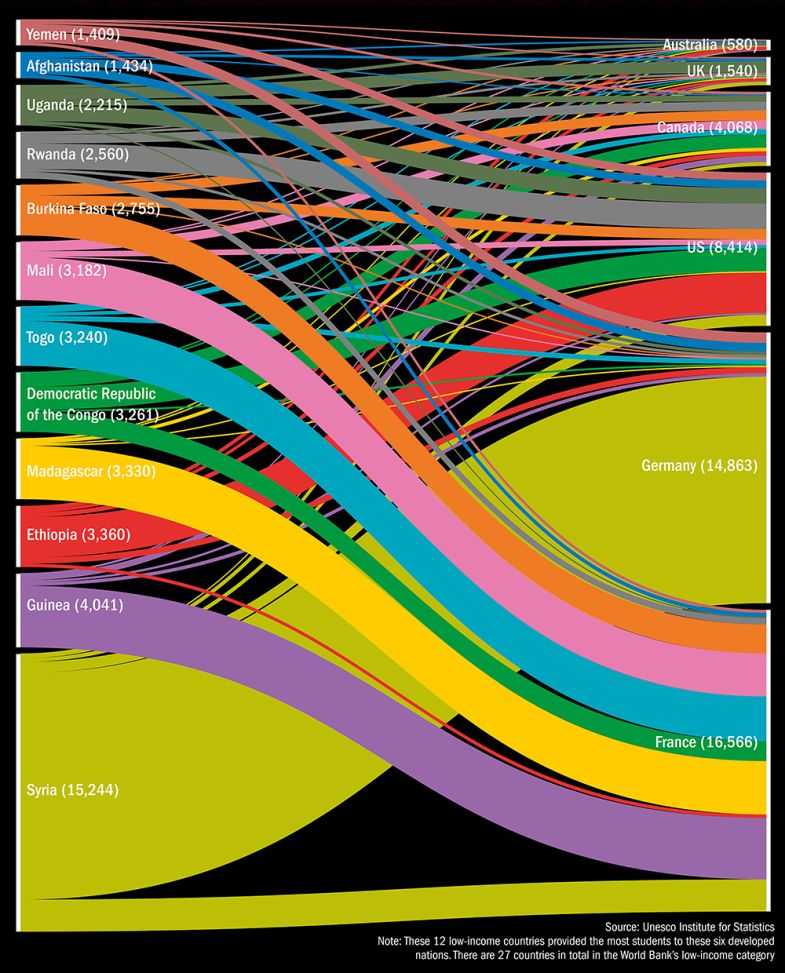

A comparison on the low-income countries group alone, made up of 27 mainly African nations but also war-torn states such as Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen, suggests a smaller gap between anglophone developed systems in terms of enrolments.

For instance, Australia had far fewer students enrolled from these regions – just 843 in 2019, or 0.2 per cent of its total – a smaller proportion of its total international enrolments than the UK, which had 2,744, or 0.6 per cent. Both countries have also seen the share fall over the past 10 years; in 2010 it was 0.5 per cent in Australia and 1 per cent in the UK.

However, the US did not fare too much better; its total enrolment from low-income countries was almost 11,000 students in 2019, but this was still only 1.1 per cent of its international intake.

Of the main anglophone nations, Canada enrolled the most from the poorest countries as a share of its overall enrolments, 4,782 in 2019, or 1.7 per cent. This was almost double its numbers in 2010 but represented a drop in the share of total international enrolments owing to the country’s huge expansion in overseas recruitment in recent years.

However, enrolments from the poorest countries appear to be far higher in continental European systems, where international fees tend to be much lower or even non-existent. For instance, enrolments in France from low-income countries reached 20,000 in 2019, 8 per cent of all incoming students, and in Germany they totalled more than 15,000, or almost 5 per cent of its total.

How students move from low-income to wealthier countries

A more detailed look at the statistics also reveals interesting underlying data: a major proportion of low-income country enrolments in Germany in recent years have been Syrian students, while in France they often hail from francophone Africa.

So to what extent do these figures reflect better targeting of scholarships for some of the poorest communities in the world?

In Germany, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) did run a programme for Syrian students called the Leadership for Syria scholarship, but this was a highly targeted scheme that sought about 200 of the most talented students through a series of intensive interviews in the Middle East and Germany.

According to Christian Hülshörster, director of the southern hemisphere scholarship programmes at the DAAD, the vast majority of Syrian students in the German figures were likely to be the children of refugees who entered Germany as part of the country’s policy to accept hundreds of thousands of people fleeing the war.

“They are not typical exchange students because their whole families moved to Germany,” he pointed out.

However, many of these students will still have benefited from DAAD money to support their studies, through two schemes that help refugee students integrate in universities by funding language classes, counselling support and other initiatives.

Dr Hülshörster said that, as for an annual DAAD leadership programme for African countries, the original aim of the one-off Syria scholarship was to help train people who could then return to their country and use their new skills to benefit their societies.

However, the path the Syrian conflict has taken meant those graduating from the programme were now likely to be helping to meet key skills shortages in Germany and elsewhere in Europe.

Although Syria is clearly a special case, given Germany’s lead in accepting refugees and the inability of graduates to return, this touches on one of the key dilemmas associated with designing scholarships for students from low-income countries: preventing brain drain.

Jamil Salmi, former coordinator of the World Bank’s tertiary education programme and emeritus professor of higher education policy at Chile’s Diego Portales University, said that scholarships and other partnerships between universities in the Global North and South were a “concrete way of showing that rich countries and higher education institutions are not paying only lip service” to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

However, he added, it was also important “to recognise that scholarships often benefit students from the elite in low-income countries. Applying a strict ‘economic need’ filter is therefore essential, as well as a gender filter to ensure greater opportunities for female students.

“Partnerships that focus on capacity building in higher education institutions in low-income countries can also be effective to support the equity agenda,” continued Professor Salmi, provided they were designed collaboratively and “aligned” with the development needs of universities in the South.

Ellen Hazelkorn, professor emeritus in higher education policy at Technological University Dublin and a former policy adviser to the Republic of Ireland’s Higher Education Authority, said that without such considerations, the risk of brain drain from developing nations was real.

“There are countries in parts of the Global South that are really haemorrhaging graduates and skilled people, mainly from the middle class. You see that in places like Syria and Afghanistan in terms of who is leaving or able to leave,” she said.

The pandemic, and the shift to online working, may also have changed the emphasis that universities in the Global North may need to take when it comes to helping students in the Global South.

For instance, while access to online programmes might be easier, this raised fundamental questions about whether there was equitable access among students in poorer countries to adequate technology, Professor Hazelkorn added.

Professor Salmi also warned that “we should avoid a new division of labour where students from low-income countries stay at home and study online at universities in the North, while students from the North have the privilege of face-to-face studies.

“But it is certain that we can build on the lessons of the pandemic to use online teaching, learning and research more systematically and effectively to strengthen collaborative efforts between higher education institutions in the North and those in the South.”