Let’s face it: pronouns aren’t what they used to be.

For a long time I have found it annoying when pronouns alternate throughout a piece of writing, referring to the same body sometimes as she and sometimes as he; or when they appear as the hideous hybrids (s)he, he/she and s/he. We could write more gracefully by replacing singular with plural nouns, which would agree with gender-neutral plural pronouns (thus, not “a student has his” but “students have their”).

But is agreement necessary? As language catches up with culture, new pronouns have been invented to acknowledge gender-variant identities. Just as importantly, the gender-neutral plural pronoun “they” and its inflected forms, “them”, “their”, “themselves” (and “themself”!), are being used to refer to one person. To mark gender inclusivity, “they” has arrived at the party.

Perhaps I should not have been surprised. For more than 20 years (at least since the publication of Judith Butler’s foundational text, Gender Trouble), my field, literary studies, has been paying lip service to the idea that gender identification is a social construct. Now, however, students are challenging us to take these theories to heart.

One of my enlightened colleagues has started to walk the walk. She begins every semester by clarifying the issue of pronouns and gender. On the first day of class, her students go around the room and introduce themselves by answering several questions including, “What are your pronouns?”

I myself first encountered this sea change last year. Until I taught Jamie (whose name has been changed to protect privacy), I wasn’t sensitive to gender variance in my day-to-day life. When another student in the class told me that she was doing a project with “them”, I was confused, failing to recognise that the gender-neutral plural pronoun was being used in the singular – that is, “them” was only one person, Jamie. Jamie, who considered themself to be a trans male, preferred being referred to as “they” instead of “he” or “she”. When I had coffee with them (Jamie), they cautioned against regarding those with non-binary identities as “special snowflakes”, expectant of attention and praise just for being themselves, or as being somehow “not real”.

This semester, Alex (whose name has been changed for privacy), another gender-variant student, is using the newly invented gender-neutral pronouns zhe (or ze) and zer (or zir). Alex was concerned that zir identifiers would be perceived as lacking credibility because they are “made up” and lack the universal acknowledgement that comes with standardisation. (The gender-inclusive title Mx is gaining just this type of acceptance, especially in the UK and Australia.)

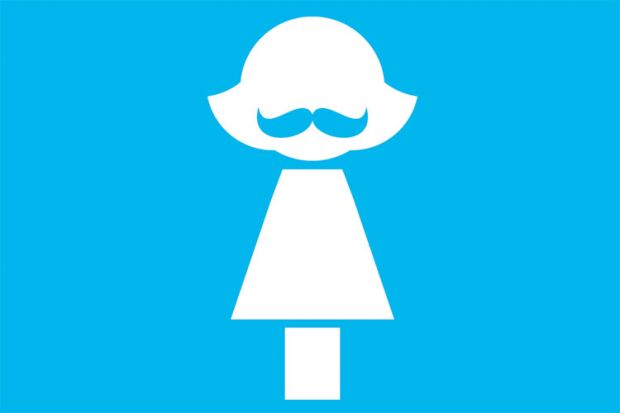

I am still hyper-aware of gender at every turn, as I try to use students’ preferred pronouns naturally. Gender variance is more than a fashion trend. We all need to take special care not to offend by making assumptions about what we cannot see and do not know.

Let me end with a heartfelt plea for sensitivity and inclusiveness. Language is something that we all share; it makes us human. The sooner we adapt language to embody the lived realities of gender, the sooner we will let people be who they are without thinking twice about it. “They” is here to stay.