Source: Elly Walton

If Oxford and Cambridge increased market share, they would reduce the exclusivity and value of their degrees

The commercialisation of higher education was first floated in the UK in the Thatcher years, along with the introduction of “user” charges and privatisation in utilities, transport, social services and health. Thirty years later, direct funding of English higher education has been transferred to graduates, higher education institutions have become better at shaving costs and at marketing, and international students generate extra revenue.

But is UK higher education any closer to a genuine capitalist market powered by the profit motive? Not really.

Most of the competition driving the sector is not about buyer-seller economics in the marketplace. It is about older qualities such as institutional prestige, selection on to high-demand programmes and research excellence.

There is conventional commerce only at the margins of mainstream activity: international students, short training programmes, for-profit providers, online delivery, commercial research and consultancy. That is as far as it goes. The core activities – first degrees, doctoral places, mainstream research – remain stubbornly non-commercial in essence.

Under the £9,000 tuition fee regime, the government has maintained close regulatory control, the public cost of higher education may have increased, and, most importantly, the economic laws governing the sector are unchanged. The same is true of other countries with limited marketisation of their higher education systems, such as Australia.

The “market” is a metaphor for competition and, for politicians, an excuse for devolution of responsibility for outcomes from government to higher education institutions. As a technical descriptor it is grossly inaccurate.

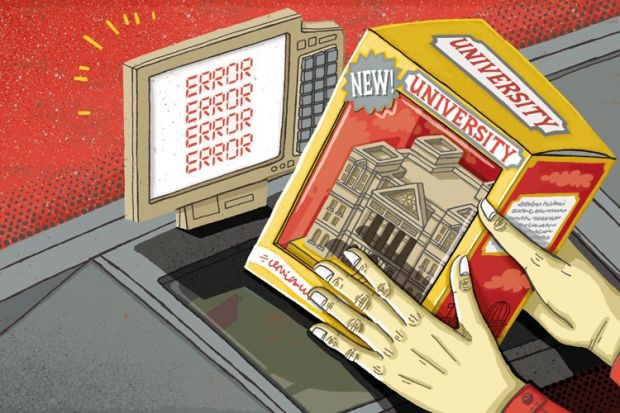

The fact is that it is impossible to introduce a genuine economic market in higher education – one driven by the profit motive, open contestability of provision, bankruptcy sanctions, free consumer “shopping” and choice, allocative efficiency and the struggle to maximise market share – without vaporising much of the product itself.

This is why no government anywhere has introduced a full-blown capitalist market, despite three decades of talk. Attempts to fully commercialise universities and research run up against insuperable limits. Higher education is very different from communication and transport, where services can be privatised or commercialised without changing the product.

Why is it impossible to create a fully capitalist higher education and research sector, whether in the form of “luxury” or “mass market” higher education or some combination of the two?

Although the political obstacles to marketisation are formidable, ranging from vested interests to policy goals such as social access, this is not the ultimate limitation. The constraint is the intrinsic social nature of the “goods” in higher education.

In economic terms, higher education produces status goods – student places and degrees associated with desired personal attributes and social outcomes. The most sought-after “products” are places in elite universities and on courses such as medicine.

Social status cannot be infinitely expanded without changing its nature. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge cannot service all possible student demand, in the manner of luxury carmakers. If they increased market share they would reduce the exclusivity and value of their degrees.

Likewise, consumer power cannot truly govern selective universities. They remain producer controlled. As the disgruntled consumer walks out of the door, she or he passes a queue of others waiting to enter. Although elite universities are wise to maintain student friendliness, if only to attract the high-quality students they want, this is not an orthodox consumer-driven market. Genuine customer focus takes root only among lower-status providers with unfilled places.

Nor can university research be fully commercialised without losing the basic curiosity-driven programmes of enquiry that are both integral to economic innovation in industry, and underpin the social status of the leading higher education institutions. Corporations will not fund blue-skies research with long lead times and little prospect of their being able to capture its benefits. All over the world, basic research is largely sustained by governments or philanthropy, not markets.

In the US “market”, universities depart from capitalism at every turn. The government heavily funds student loans and research as in the UK. Ivy League universities spend lavishly on prestige facilities generating no financial returns. They are not primarily driven by revenue. Money is merely the means to the real end, their role as engines of status. They maximise research (research performance feeds university status) while keeping the lid on student numbers. Tuition charges are often set well below “sticker” prices, allowing institutions such as Harvard and Stanford universities and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to shape their preferred student mix, on social not economic grounds.

Higher education could be turned into a field of profit-driven firms only by deconstructing the leading and middle-level institutions and much of the research they produce, eliminating the associated social status and “knowledge goods”. For better or worse, these functions generate much of the social value of higher education – so it is not going to happen.