Is there a connection between the history of slavery and the birth of American democracy? Manisha Sinha’s remarkable study of abolition in the US from the 17th century to the end of the 19th could help to answer that question. Across more than 600 pages, with reference to a vast literature including an impressive range of primary sources such as letters and diaries, The Slave’s Cause traces themes of interracial collaborations, women’s role in the struggle, and the black agency that led to the dismantling of an institution built on the subjugation of other human beings. The result is an outstanding reference book that highlights the links between American, Haitian, British and French abolitionist movements, and black and white Americans’ political and intellectual journey towards gender, social and racial equality.

In the UK, historians of abolition were criticised, often justly, for considering only those who brought the system to an end in mainland Britain, obscuring the struggles of slaves, the free black men and women who challenged slavery, and the British subjects who questioned their country’s involvement in the slave trade. One of the first major 20th-century works on the history of slavery and abolition was a 1923 biography of William Wilberforce by Sir Reginald Coupland, a staunch advocate of empire. It remained a key source until Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery in 1944, which ignited a controversy about the links between Britain’s Industrial Revolution and the financial legacies of slavery. But in the US, unlike in the UK, slaves had not been confined to far-off West Indies islands, shielded from Americans’ daily lives. The constant reminder of the contradictions inherent in the system made slavery and the struggle for abolition part of America’s social fabric.

In the book’s first half, Sinha focuses on “first wave” abolitionism. The case for abolition was being made as early as 1652 in Rhode Island by Roger Williams, who argued for limits to the number of years that Africans and Native Americans could be held in bondage. Over the next 50 years, key roles were played by Quakers, inspired by Anthony Benezet. He was instrumental in internationalising a movement that eventually reached British shores in the second half of the 18th century. Those pioneers were part of complex networks that drew support from ordinary people as well as from wealthy and dedicated political and religious groups. Sinha also examines black pioneers including the scholars Juan Latino in 16th-century Spain and Anton Wilhelm Amo in 18th-century Saxony, and anglophone writers such as Lucy Terry Prince, Phillis Wheatley and James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African who ended up free but destitute in 18th-century England.

First wave abolitionists also included “revolutionary” anti-slavery groups, who fought for emancipation in the “slaveholding Republic” until the 1820s. Among their supporters was Thomas Paine, who questioned colonists’ claims to be fighting for humanity, liberty and self-determination while simultaneously supporting slavery, and black intellectuals such as Lemuel Haynes, a clergyman who ministered to a white congregation in Vermont. Although many revolutionary abolitionists fought for what they saw as the promise of a free and strong republic, others took up arms alongside the British during the American War of Independence and ended up in Canada and Australia, on the streets of London, and in Sierra Leone. Although these black loyalists immigrated to these places as free men and women, many ended up in dire circumstances; while for those remaining in the new republic, a century of struggle for emancipation still lay ahead.

One of the most significant themes in the book’s first half is the impact of the Haitian revolution of 1791-1804. In considering the intellectual, cultural and political connections between Haitians and African American abolitionists, Sinha argues that Haitian revolutionary ideas and exchanges helped to shape black activism in the US, redefining strategies and reviving interest in emigration to Africa and Haiti. They also cemented the fight for immediate (as opposed to gradual) emancipation and informed the “free labour” argument made by black businessman James Forten and others that workers would be more productive when not enslaved. Petitioning, debating and preventing the kidnapping of free blacks were the hallmarks of “political antislavery”, which advocated working with or putting pressure on Congress when constitutionally possible.

The book’s second half is equally powerful, as Sinha examines transnational and interracial abolitionism involving North Americans and Europeans, including collaboration between black and white women. It is here that her welcome focus on black agency comes through most strongly, particularly in the deconstruction of racist ideologies. Thomas Jefferson’s ambiguous position on slavery and emancipation exemplified pervasive racism: although he condemned the slave trade in the 1770s, by 1785 his views on the inability of blacks to fully integrate into the republic were well known. Sinha also emphasises that black agency preceded white abolitionism, showing that white abolitionists often responded to black demands and analyses of key events by incorporating the main points into their literature. The critique of imperialism by white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, for example, echoed the refusal by African Americans such as Robert Purvis to support the dubious African Civilization Society, set up by whites in favour of abolition but against the granting of US citizenship to free blacks, arguing that they would be better off in Africa.

As Sinha highlights, there were marked contrasts between European abolitionists, who favoured colonisation and empire-building, and American abolitionists, whose long-term plans included women’s rights, the fight for the rights of the working class and anti-imperialism in Ireland and India. The second wave of abolitionists, which included groups such as the New England Anti-Slavery Society founded in 1831, was dynamic and multilayered. But pro-slavery advocates, including planter and senator James Henry Hammond, were well organised and politically powerful, as evidenced by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. It granted slaveholders the right to send slave catchers across the border into Canada, where slavery was illegal. This law precipitated defiant direct action, including an increase in maritime, plantation and urban slave rebellions throughout the 1830s and 1840s. In a tense environment in which the lives of free blacks were also in jeopardy, a number of African American abolitionists evinced support for emigration. Robert and Thomas Hamilton promoted these views into the late 1850s via their Weekly Anglo-African newspaper, which enthusiastically covered the journey to Liberia by black journalist Martin Delany.

In the 1860s, fractious relations between Northern and Southern states took a dramatic turn. As Sinha puts it, “The Civil War…was an ‘abolition war’. It proved to be the midwife of emancipation”. President Abraham Lincoln’s desire to preserve the union at all costs was challenged by radical pro-slavery states, and abolitionists’ acceptance of the inevitability of war forced him to reconsider his position. Sinha argues that as Lincoln’s reputation as the “Great Emancipator” was being forged, the long history of black activism and direct action was being obscured. She concludes by positing that not only the civil rights movement in the 20th century, but also the election in 2007 of Deval Patrick, the first African American governor of Massachusetts, the appointment in 2015 of Loretta Lynch as the first female African American attorney general, and even Barack Obama’s presidency, are all legacies of the long fight for emancipation and social justice initiated by African Americans.

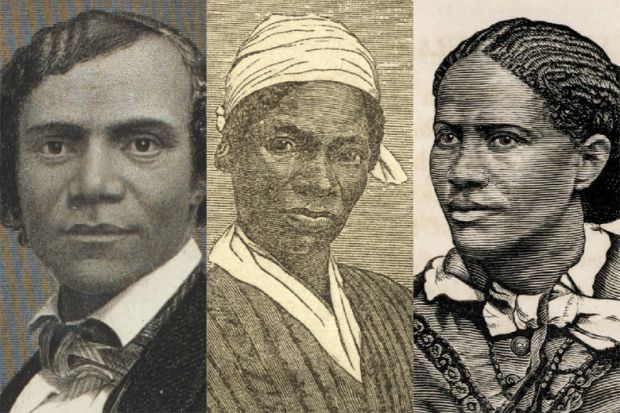

This well-written and accessible book has many strengths, but Sinha’s able deployment of so many sources makes it outstanding. Looking past the image of a kneeling slave that British readers are still used to seeing in works on this subject, Sinha brilliantly shows how African Americans themselves worked tirelessly to make freedom a reality.

Olivette Otele is senior lecturer in history, Bath Spa University. Her research focuses on the links between history, memory and geopolitics in relation to British and French colonial pasts.

The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition

By Manisha Sinha

Yale University Press, 784pp, £25.00

ISBN 9780300181371

Published 3 May 2016

The author

Manisha Sinha, professor of Afro-American studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, “was born and raised in India in a family of historians. My father was an army officer who joined the British Indian Army during the Second World War, and he has written a number of military history books. My mother was a Gandhian who participated in the nationalist movement in college. All my siblings studied history in university. One of my earliest childhood memories is having heated historical debates at the dinner table!”

Manisha Sinha, professor of Afro-American studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, “was born and raised in India in a family of historians. My father was an army officer who joined the British Indian Army during the Second World War, and he has written a number of military history books. My mother was a Gandhian who participated in the nationalist movement in college. All my siblings studied history in university. One of my earliest childhood memories is having heated historical debates at the dinner table!”

She recalls having “wonderful history teachers and mentors” at school and as an undergraduate at the University of Delhi. “Most were women and the idea of being a female historian seemed natural.”

Sinha was a consultant on the PBS documentary series The Abolitionists. “The average American rarely thinks of the crucial role of abolitionists and the enslaved themselves in the coming of emancipation. We normally assign all credit to Abraham Lincoln. The series helped to correct some of that imbalance. But it chose to highlight only a handful of abolitionists. Ironically, I advocated for featuring Harriet Tubman, who will now adorn the front of the US $20 bill, rather than Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose commitment to abolition and black rights waxed and waned. I thought the series ought to have included at least one black woman abolitionist.”

Of the countless historical figures she focuses on in The Slave’s Cause, who does she most feel should be better known to Americans today?

“I can think of at least four abolitionists, men and women, black and white, who were crucial to building the American movement and ought to be better known. The first is Theodore Weld, who wrote some of the most influential abolitionist texts and organised the lecturing agency system of the American Anti Slavery Society. His remarkable instructions to abolitionist agents on how to respond to violent mobs without resorting to violence anticipated the civil rights movement by a hundred years.

“The second is the fugitive slave abolitionist James W.C. Pennington, who wrote one of the first responses to scientific and popular racism, besides penning his own narrative. Pennington toured Britain and received an honorary doctorate in theology from the University of Heidelberg in 1849. On its 625th anniversary, the university established a scholarship in his name, for which I delivered the inaugural lecture and Barack Obama sent his greetings.

“Among the women, I found the abolitionist feminists Lucy Stone and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper the most intriguing. Unlike suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Stone did not break with the abolition movement after the Civil War or ever give up on the abolitionist commitment to racial equality. And I love the fact that she refused to change her maiden name after her marriage. Francis Harper is virtually forgotten today but she was one of the most popular black women orators and writers of her day. She spoke of the intersectional oppression of race and gender long before it was fashionable. As she put it, ‘You white women speak of rights, I speak of wrongs.’”

Asked if she could change one thing about her institution or the US higher education sector, Sinha observes, “Perhaps the thing that shocks me the most in the US is how the universities here are administered like private corporations on a profit maximisation principle, rather than for the public good. Even state universities in which I have taught have fairly steep tuition fees compared to Europe, Australia and India. The entire university sector in the US should be made more equitable and accessible. Institutions of higher learning should address the gross economic and social inequalities of American society instead of perpetuating them.”

Are there any early career scholars in her field whose work she finds particularly commendable? “I think young African American historians are really redefining US history, including Kidada Williams, Talitha LeFlouria and Ibram Kendi, to name only a few.”

Sinha has argued that the values and political positions espoused by Bernie Sanders, the Democratic Party presidential hopeful, are “as American as apple pie”. Is she surprised at the breadth of support for his campaign?

“Sanders’ campaign against economic inequality has a long antecedent in the history of American democratic radicalism, in the abolition, labour and feminist movements. It struck a chord with many Americans after the recession and growing inequality brought free market ideas into disrepute. I think it is wonderful that he pushed the Democratic Party to the left in the primaries and perhaps laid the foundation for it to be refashioned as a genuine social democratic party. I think of him as extending President Obama’s legacy rather than overturning it.

“In the 2014 Congressional and state elections the Democratic Party ran away from Obamacare and did not let the president even campaign for their candidates. They deserved the drubbing they received when they lost the Senate and many state governments to the Republican Party. Even Hillary Clinton is far more hawkish than Obama and distanced herself from Obama’s foreign policy decisions in the Middle East. Of course, now the Democratic National Committee, which runs the party, and Clinton are embracing Obama’s mantle when it suits them.”

What gives her hope? “Young people! When I came to the US during the Reagan era, I never imagined we would elect our first black president in my lifetime. Today it is the millennials who are moving beyond the shibboleths of the Cold War and leading grassroots activism from Occupy Wall Street to Black Lives Matter. They are behind the Bernie Sanders phenomenon this election season.”

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: They all fought the chains