How did Germany and Austria’s elite musical institutions navigate the vicissitudes of early 20th-century European history? To what were the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic orchestras forced to adapt, and how much autonomy was each able to preserve? As the Wilhelmine and Habsburg monarchies collapsed, their successor republics tottered and fell, and Austro-Fascism and/or Nazism emerged in their place, what political intrusions threatened these illustrious ensembles, and how far were they successfully kept at bay?

Fritz Trümpi’s engaging comparative study demonstrates persuasively that the answers to these questions varied greatly. He underlines that the experiences of each orchestra under Nazism unfolded in ways that were shaped by their different traditions, organisational structures, pre-existing relations to the state and by the contrasting qualities of their inherited brands. The Vienna Philharmonic, with its strong ties to the court opera house tradition, gave only a few symphony concerts a year, offering a highly conservative repertoire to the inhabitants of a rarefied Viennese habitus, and played throughout the Third Reich on its identity as an orchestra strongly associated with its home city. The Berlin Philharmonic, by contrast a full-time symphony concert orchestra, was associated from the outset with the speed and excitement of modernity: whether it was playing a new repertoire, embracing touring, experimenting with broadcasting and recording technology, or developing concert series that sought to take art music to wider audiences, the orchestra was forced by its very independence to adapt to the opportunities and threats of the changing marketplace for leisure and edification.

This was also its Achilles heel, however, as economic challenges forced a growing need for civic subsidy and, eventually, the effective socialisation of the orchestra during the Depression. It was thus the already-existing fact of public ownership, rather than the events of the Nazi seizure of power itself, that left the orchestra open to political interference after 1933. Its Viennese rival, meanwhile, a notionally autonomous association, retained a superficial element of independence even after the union of Austria with Germany in 1938.

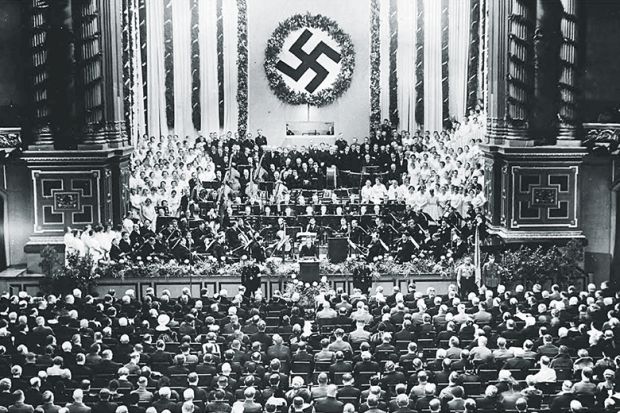

In different ways, however, both orchestras became the playthings of their immediate political overlords. The Berlin Philharmonic became prestige cultural ambassador of the Reich under the patronage of Joseph Goebbels, undertaking extensive tours to allied and occupied countries, while the Vienna Philharmonic flourished under the protection of Baldur von Schirach, the Gauleiter of Vienna. Deep-seated competition between two elite institutions, sustained by long traditions of Prussian-Austrian rivalry, gained new energy in the tangled political culture of the Third Reich. One found its activities sutured to the agendas of the regime through its embrace of Greater German nationalism, the other through a stress on local rootedness, continuity and authenticity. But both found their niche and both their rewards.

Does the notion of a “political orchestra” help us to understand the co-option of elite institutions for the cultural life of the dictatorship? It might be argued that the implied antonym – “the unpolitical orchestra” – and the corresponding suggestion of a narrative arc from pre-political innocence to one of “politicised” subjection to fascism inadvertently reinscribes those myths that the book works so hard to resist. But this is, nonetheless, the best book on orchestral life under Nazism, and its excellent translation is to be warmly welcomed.

Neil Gregor is professor of modern European history, University of Southampton. He is writing a book on symphonic concert life in Nazi Germany.

The Political Orchestra: The Vienna and Berlin Philharmonics during the Third Reich

By Fritz Trümpi Translated by Kenneth Kronenberg

University of Chicago Press, 344pp, £35.00

ISBN 9780226251394 and 1424 (e-book)

Published 12 December 2016