What is friendship? Can it be quantified, and how useful is this intangible phenomenon in predicting human behaviour? For those interested in how personal relationships influence actions, particularly in the political realm, Sheila Fitzpatrick’s impressive new study is a welcome addition to the debate.

Historians of Russia have recognised the informal and personalised nature of power in the tsarist and Soviet regimes and the weakness of formal institutional structures, but they have mainly considered utilitarian kinds of personal relationships, such as patronage networks or clientelism, the reciprocal bonds based on mutual advantage and ruled by quid pro quo. But these models have not proved entirely satisfactory, and it may be time to turn to the trickier matter of what Carl Schmitt called “existential” friendship: affectionate reciprocal bonds based on shared understanding, and consisting of perceived shared traits, virtues, opinions and experiences. But how far do such personal relationships shape political behaviour? Fitzpatrick foregrounds this question as she paints a colourful group portrait of Josef Stalin’s “team”, a circle of the Soviet leader’s friends who were drawn together not only by shared ideological principles but by a common history, culture and personal tastes and traits.

A decade ago, in the journal Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, Fitzpatrick declared that “Soviet political history has been under a cloud for the past 20 or 30 years” and issued a call for new work and approaches. In the 1970s, the focus of historical research on the Soviet Union shifted to social and then cultural approaches; when the post-1991 archival turn refocused scholarship towards provincial history, central politics remained sidelined. On Stalin’s Team builds on important exceptions to this rule, including the work of John Archibald Getty, Oleg Khlevniuk, James Harris and Yoram Gorlizki. Fitzpatrick brings her methods as a social historian to bear on the murky world of Kremlin politics, focusing on everyday practices and looking at the “Stalin team” in terms of the implicit rules of the game.

In the mid-1920s, in the wake of the death of Vladimir Lenin, an embattled Stalin began to build his team as rival factions competed for leadership of the Soviet Union. His band of merry men, Fitzpatrick notes, were not the educated, upper-class, European-travelled intellectuals of the Communist Party in the mould of Lenin and Trotsky, but men with limited education, who were less cosmopolitan and more “proletarian”. It was largely an ethnic Russian group, but with a strong contingent linked to the Caucasus, and the atmosphere was one of “conspiracy, companionship and crude masculine humour”. The familiar form of address was often used even in official correspondence, in a break with the more formal and businesslike conventions of Lenin’s team.

In Fitzpatrick’s view, the Russian civil war of 1918-21 was a great formative experience and the wellspring of a new macho culture, with Stalin’s team cemented by the fellowship of male veterans who had bonded through service at the front. They drank and smoked together and, even into the 1930s, continued to wear a version of military uniform in civilian life. For Stalin’s elite, political and social life were heavily intertwined. He socialised with the team in their Kremlin apartments or at his country dacha, and they, along with their wives and children, comprised virtually his entire social life.

Studying political history in terms of official institutions and policy decisions has not always worked well for the Stalin era, as its formal structures could be so misleading. Thus Fitzpatrick’s focus on this informal friendship group is particularly fruitful. Under Stalin, membership of the team and of the party’s most important organ, the Politburo, were closely related, but not identical, as Stalin typically preferred to consult an informal inner circle outside official meetings.

While the names will be familiar to scholars, Fitzpatrick allows us to put faces to those names. We meet Vyacheslav Molotov, Stalin’s closest associate in these years, dull, uncharismatic, but with endless work capacity; Lavrenty Beria, smarmily deferential and maliciously witty; Lazar Kaganovich, the bully with an inferiority complex about intellectuals; Stalin’s “peasant” protégé Nikita Khrushchev, who masked his sharp brain under a homespun exterior; and three friends who came to Moscow from the Caucasus in 1926 to join the team, the dashing young Anastas Mikoyan, the hot-tempered and charismatic Grigory Ordzhonikidze and the charming Sergei Kirov. Klim Voroshilov, Mikhail Kalinin, Jan Rudzutak, Valerian Kuibyshev, Georgy Malenkov and Andrei Andreev also feature as sharply drawn key players.

The team feared Stalin, their captain and player-coach, but they also admired and respected him, particularly for his boldness and cunning. For more than three dangerous decades, this group would survive as a remarkably stable core, and then form a ruling collective after his death in 1953. Unchallenged leader though he was, Stalin (unlike Hitler) chose to rule surrounded by powerful figures who were loyal to him personally, but also operating as a cohesive unit. As Fitzpatrick shows, these men were not competitors for leadership, but neither were they political nonentities. They ran important sectors such as the railways, military and heavy industry and were advocates in government for the institutions that they headed. But while institutional interest was acceptable, personal and ideological interest was not. Most important policy discussions were discussed as a group. While Stalin did not need their agreement, when he sensed that it was lacking he sometimes backed off or waited for them to come around. Fitzpatrick explains Stalin’s famous use of “dosage” – slow, incremental destruction of political rivals – as a method informed by group dynamics, with Stalin backing off if members’ discomfort became too severe.

Fitzpatrick could have been clearer on the importance of ideology. She argues that while shared principle was not the team’s uniting factor, nevertheless core beliefs did matter to Stalin. “Why – except for ideological reasons – would Stalin and the team have embarked upon collectivization at the beginning of the 1930s?” she asks, suggesting that Stalin did not want power for its own sake. Other scholars might counter, however, that collectivisation was as much about establishing his power as about increasing production, as a move that would enable the party to extend its political dominance over the vast, under-administered Russian countryside. One may also ask if Fitzpatrick is reading history backwards to an extent, in focusing on comrades who made it through the tumultuous 1930s and thus exaggerating the team’s stability.

Nevertheless, this is a rare and highly accomplished piece of scholarship, and an accessible volume that I would recommend to expert colleagues, students and non-historian friends alike. Although the book is impeccably researched using archival sources, as would be expected of a scholarly monograph, Fitzpatrick shows herself to be a master storyteller as well. Readers will laugh out loud at accounts of exchanges between squabbling Bolshevik leaders that bring their vivid personalities to life, and will be drawn into the simmering drama as lively characters leap from the pages.

Of course the question remains: do we really need another Stalin book? In the past six months alone, two substantial biographies by equally renowned scholars have been published. My answer, with respect to On Stalin’s Team, is a resounding yes. Fitzpatrick’s innovative approach situates Stalin firmly in his personal milieu for the first time, helps to elucidate how he actually exercised power through his team, and offers a compelling sense of the personalities and relationships at play in the Soviet elite that will prove invaluable in interpreting party and government records via their human context.

Lara Cook is lecturer in Russian history, University of York. She is completing a monograph on the practical functioning and internal culture of Lenin’s government.

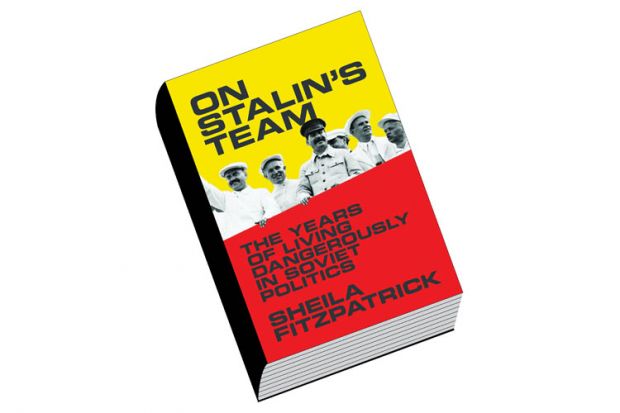

On Stalin’s Team: The Years of Living Dangerously in Soviet Politics

By Sheila Fitzpatrick

Princeton University Press, 384pp, £24.95

ISBN 9780691145334 and 9781400874217 (e-book)

Published 28 October 2015

The author

Sheila Fitzpatrick, honorary professor of history at the University of Sydney, grew up in Melbourne, which “may have given me a slightly outsiderish or detached perspective, despite all my years in the US and the UK”. Doctoral study at the University of Oxford, followed by many years as an academic in the US, took her away from Australia for 48 years.

Sheila Fitzpatrick, honorary professor of history at the University of Sydney, grew up in Melbourne, which “may have given me a slightly outsiderish or detached perspective, despite all my years in the US and the UK”. Doctoral study at the University of Oxford, followed by many years as an academic in the US, took her away from Australia for 48 years.

Sydney, she says, “is great: sun, beaches, good quartets to play in. I am a violinist in my spare time; mainly classical, but I’ve been persuaded to play jazz with a colleague, Marco Duranti.”

Of her early years, Fitzpatrick recalls being “an intellectual child, which I got from my family. I wasn’t studious, as it wasn’t necessary in my school, but I read a lot. I wasn’t studious at university either, as I found the social life too interesting. I became a hard worker in graduate school at [the University of] Oxford, perhaps out of unhappiness. But I had also got hooked on research by my BA Hons thesis in [the University of] Melbourne.”

Her undergraduate self was “shy but not solitary, and ambitious in the sense that I was determined to leave Australia as soon as possible, which meant getting a first and a scholarship”. When she moved from Melbourne to Oxford, she found it “culturally familiar; we were all overprepared for England from reading. But academically it was a disappointment in my field. And I was not used to being an oddity because of being a woman, which I felt was the case in Oxford then.”

In her 2013 book A Spy in the Archives: A Memoir of Cold War Russia, she recalls the kindness and help she received, as a young Western historian in Moscow, from a senior government figure, Igor Alexandrovich Sats. Was this unusual? Sats, she says, “had a tendency to collect waifs and strays. In general, there was residual fear in the Soviet Union in the late 1960s about making friends with foreigners, but many people were friendly.”

Which of Stalin’s associates would she most like to have spoken to as frankly as she did to Sats? “Lavrenty Beria. He is the one we have least reliable information on. After his fall, he was scapegoated, with nobody except his family willing to say anything except how evil he was, and there is no personal archive. I found him the hardest to pin down for this reason. Of course, anyone might want to talk frankly to Stalin, but it would have been dangerous to become someone in his line of vision.”

Asked if there is a word or expression in Russian that tells us something interesting about the Russian personality, in Soviet times or more generally, she offers, “Well, there is ‘seichas’, meaning literally (I am coming) at once, which in normal speech means I am coming, but not at once. Russians have improved in this respect, but I used to be astonished at their attitude to time, which included an inability to make dates further than a day ahead – they always said, Ring me on Wednesday, or whatever, which could be really annoying if you didn’t have easy access to a phone.

“One friend of mine who had a lot to do with Soviet Russians in the 1940s claimed there was an expression ‘Chtoby ne bylo luchshe’, meaning, Don’t let things get better (implying a fear of promises of a radiant future). That would be nice if true, but I never heard any Russian say it.”

What gives her hope? “I tend to focus on the possible bad rather than good outcomes. But meeting Misha [her late husband, the physicist Michael Danos] in 1989, an annus mirabilis anyway, gave me the sense that, who knows, good things may turn up unexpectedly. Which, in the case of my return to Australia in 2012, they did.”

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: Friendship is a life sentence