I recently learned about the first “white paper” protester, whose gesture of holding up a blank sheet of paper was widely copied in a wave of Chinese protests against Covid-19 restrictions last November. She has been tentatively identified as Li Kangmeng, a student at Nanjing Media College.

Out of curiosity I searched for her on Weibo, China’s heavily censored microblogging site. Surprisingly, my search turned something up, dating from just after Li’s rumoured arrest. A Chinese netizen, confused by messages about “saving Li Kangmeng” had blurted out “but who is Li Kangmeng? What happened to her? Why does she need saving?” An answer was censored, but the question had somehow remained.

Perhaps, as Hannah Arendt would have said, this proves that totalitarian regimes can never fashion a perfect “hole of oblivion” to consign their opponents to; someone will always be able to tell their tale. Even less can dissenting citizens living abroad be silenced. But such regimes can certainly try, instilling fear about what will happen when they return home.

News has filtered out of China that several recently arrested white paper protesters are graduates of Western universities. A couple of those universities have issued robust statements demanding their release, but others have been less forthright. One wonders whether their silence would endure even if currently enrolled Chinese students were detained on visits back home.

I recently asked some expatriate Chinese scholars and students about the pressures Chinese students face in their overseas activism, and about what their universities should do to help them exercise their right to free speech. Some requested that I refrain from using their real names.

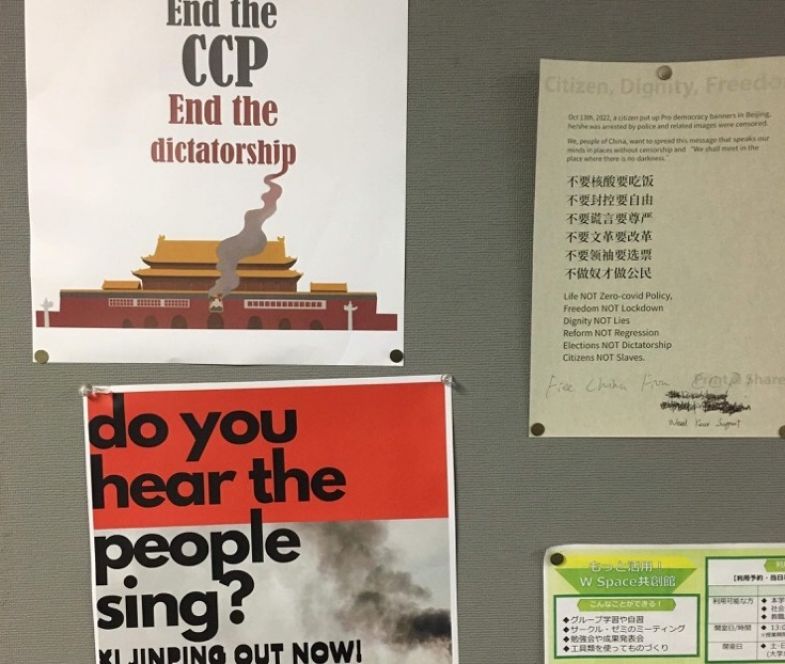

Simon Luo, a political scientist at Stanford University, testified to the courage of “young, politically inexperienced” Chinese students who spoke in solidarity with the white paper protesters during a December vigil at his university. But most Chinese students he knows at Stanford were educated in the US high school system and seemed “open-minded” and confident with critical discussion of China politics. By contrast, lecturer T.H. Jiang describes a very different atmosphere on New York City campuses, whose Chinese students mostly come direct from China and are more likely to be nationalist. But, he added, confrontations rarely amounted to more than nationalist students removing or destroying activists’ posters.

Bella, a student at a liberal arts college in the American south, spoke of the anxiety-inducing trust issues between Chinese students. Activists for greater Chinese freedoms “don’t have a formal organisation because we simply can’t risk it”, given well-founded fears of being reported by nationalistic students. She also feels compelled to avoid “long conversations with Chinese people when I don’t know their stance on things”, including “anyone who’s part of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association”.

Diane, a student at an Ivy League college, acknowledged that being in the US meant that “what I can do for the motherland is limited”. But she would still “raise my voice…until they hear the cry from China, until they stand with us on the right side of history”. However, her university’s silence during the white paper protests “makes me feel I cannot count on my school if I do get into trouble”.

According to Jiang, universities’ silence is explained by the amount of revenue they derive from fee-paying Chinese students. But everyone I spoke to agreed that universities could still do more. Bella thought administrations should uphold their values and act firmly against “foul play, like nationalist students threatening to report other Chinese students to the Chinese state security agencies”. Diane suggested that universities’ international student offices could collaborate with their law schools “to provide legal counselling” for Chinese students, and that “universities be unstinting in their efforts to negotiate with the Chinese regime” on behalf of detained students.

But would protests from abroad really make a difference for those detained in China? According to Luo, if there had been no vigils, protests or open letters for the detained white paper protesters, state security agencies might have concluded that “no one cares” about them, allowing them to be consigned to the “hole of oblivion”, at the mercy of harsher interrogation measures. Surely no university wants to be complicit in imposing that fate on any of their students or alumni.

Shaun O’Dwyer is an associate professor in the Faculty of Languages and Cultures at Kyushu University, Japan.