Enrolments in the study of languages other than English in schools and universities are falling internationally, driven by factors such as the rise of English as a global language and advances in translation technology. However, England’s frozen tuition fee is hastening the demise of university language degree programmes to such an extent that significant swathes of the country risk having no provision at all outside high-tariff institutions.

My recent research shows that, although only 47 out of a total of 97 English universities offer languages to degree level, most of the country is within a commutable distance of 37 miles (60km) from a university where languages are offered. However, with recent closures including Aston, Coventry, Huddersfield, Hull, Salford and Sunderland universities, only 17 of the 61 universities whose entry tariff is below the 2019-20 average of 128 Ucas points offer languages to degree level, and there are large cold spots in the north, east and south west of England more than a commutable distance away. Moreover, with the University of Kent consulting on the closure of languages and other programmes, this situation threatens to get worse.

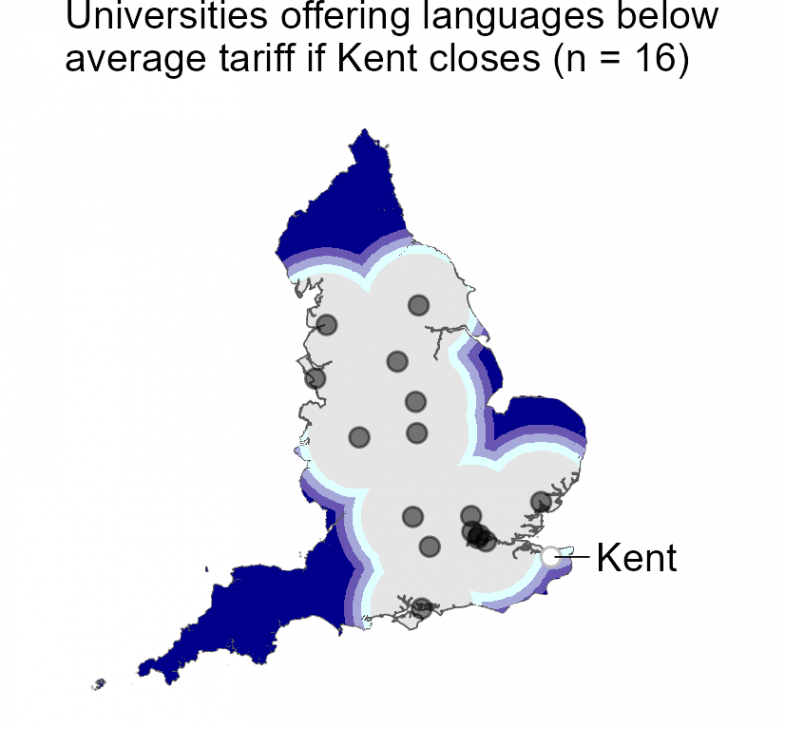

Cold spots matter because most students attend university close to home, with students from less privileged socio-economic backgrounds, mature students and certain ethnic minority backgrounds more likely to commute. If Kent decides to close its language degree programmes, the 17 below-average-tariff universities offering languages will become 16 and a new cold spot will open up in the south east. While it is not as big as those in the north, east and south west, losing Kent will mean that anyone in the south east who wants to study languages at a below-average-tariff university will have to commute to London, adding a significant financial burden and making language degree study inaccessible to most.

My research focuses on England only because education policy in schools and universities is devolved to the four nations. But cold spots are relevant elsewhere in the UK. One topical example is north-east Scotland, where language degrees were at risk even at the high-tariff University of Aberdeen until a campaign led to the reprieve of joint-honours programmes at the end of last year. Another example is Northern Ireland, which used to offer degrees in French, Spanish, German and Chinese at below-average tariffs, but now offers only Irish.

The impact of closure is clear. But to avoid it, we need to enrol more students and to ensure that language programmes are financially sustainable. Here are three things we can do.

First, we can learn about and promote language programmes at below-average-tariff universities. I have heard people say, for instance, that languages “closed” at the University of Wolverhampton, unaware of its thriving British Sign Language (BSL) programme. The website of the Widening Participation Languages Network shows which languages are offered to degree level at which universities. We can all work together to spread the word – at open days and during school visits – about those offering languages, combinations of languages or pairings of languages with other subjects that are not offered elsewhere.

Relatedly, it is important that we value the various ways in which languages can be studied to degree level in the UK. Research by the University Council For Languages (UCFL) and the British Academy shows that language degrees are “diversifying to cater for the priorities and preferences of a changing student population”. While cultural studies are of national and international importance, we must not discount degrees where languages are paired with business, law, linguistics, politics, teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL), translation and other subjects – recognising that the study of culture is often integrated within language modules and the year abroad.

Second, we should support initiatives led by UCFL, the British Academy, the Association of University Language Communities (AULC) and others to promote language education. We can make use of and promote the Languages Gateway, an online portal where learners, teachers, researchers, parents, careers advisers and employers can find opportunities, resources and information related to languages and cultures. And we can take part in the outreach and schools liaison organised by Routes into Languages.

Third, we can explore ways of designing language programmes to make them more sustainable. In a recent co-authored article, Rachel Wicaksono and I discuss the language degrees that we designed at York St John University. Rather than combining languages with multiple subjects, we devised one or two programmes per language (in languages not taught in schools: BSL, Japanese and Korean). These attract a large number of students, are financially sustainable and avoid the administrative complexity that can sometimes be associated with language degree programmes – offering one model for designing more sustainable programmes.

If we get this right, language provision can grow again. Perhaps we could even open or reopen programmes in cold spots. But doing so will require us to articulate the importance of maintaining access to degree-level language study for under-represented groups – and to translate those words into action.

Becky Muradás-Taylor is professor of languages and linguistics and director of programme design in the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies at the University of Leeds.