One of the industries that define American prosperity, goodwill and strength on the world stage is education. The US has been the destination of choice for international students wishing to study abroad for more than a century. But in an increasingly competitive global environment, we’re losing market share. Reversing this negative trend should be a priority for policymakers and all Americans.

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, there is strong bipartisan support in Washington for investing in and bringing critical industries and manufacturing back to the US – everything from computer chips and batteries to surgical masks and medicines. This rare instance of agreement on both sides of the aisle is driven by economic and national security objectives. International education, a multibillion-dollar industry, directly addresses both those concerns, and the US has the capacity right now to reaffirm its global leadership without the headaches of supply chain mishaps or the cost of constructing a single new manufacturing facility.

An American higher education remains very much in demand. The US is famed for the tradition of freedom of expression and thought on its campuses, and one tangible outcome of an American higher education is an ability to reason. While a diploma from a US institution carries prestige in its own right in many countries, employers there also want people who have genuine critical-thinking skills.

Prior to the pandemic, the number of international students studying in the US exceeded 1 million. Last year, the number recovered to 950,000 from pandemic lows and continues to grow. These students will be enrolled in 4,000 colleges and universities in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. They will contribute more than $32 billion (£26 billion) to local communities through payments for tuition, housing and other living expenses (this figure was approximately $10 billion higher before the pandemic). This makes international education the nation’s eighth-largest services export.

Moreover, in all but the rarest cases, hosting international students gains the US friends for life. Those who go back to their home countries retain a fondness for American companies, products, customs, culture and so much more, which can only benefit American commerce and global influence. Those who stay in the US, meanwhile, offer valuable expertise and drive. Some of them even go on to win Nobel Prizes.

The good news is that the current administration gets all this. Beyond the economic benefits, the Department of State regards international education as an essential element of American foreign policy: “The robust exchange of students, researchers, scholars and educators...strengthens relationships between current and future leaders,” it says, in a joint statement with the Department of Education that calls for a “coordinated national approach” to international education. “These relationships are necessary to address shared challenges, enhance American prosperity and contribute to global peace and security,” the statement adds.

Recent visa policy changes are also encouraging. For instance, international students may now apply for their F (academic) or M (vocational) visas up to 365 days in advance of the start date for a course of study. And while not guaranteed, temporary or permanent immigration status is achievable for students, unlike in some other major hosting countries.

But while the US remains the destination of choice for international students, its market share has declined from 28 per cent in 2001 to 15 per cent today. And seven of the top 10 hosting countries – Canada, China, France, Germany, Japan, Russia and the UK – have declared national international student recruitment targets, investing far more than the US does in marketing to achieve these aims.

That said, the combined capacity of those countries is small given the demand that will be generated by the expansion of the middle class in the world’s most populous countries, with which domestic university systems will not be able to keep up. Several major hosting countries are already running out of capacity, as foreign student enrolment approaches a quarter of their total enrolments. And while China is now officially declared open once again to incoming students, the country’s zero-Covid policy and treatment of international students during the pandemic will cause students and their parents to hesitate about choosing to study there.

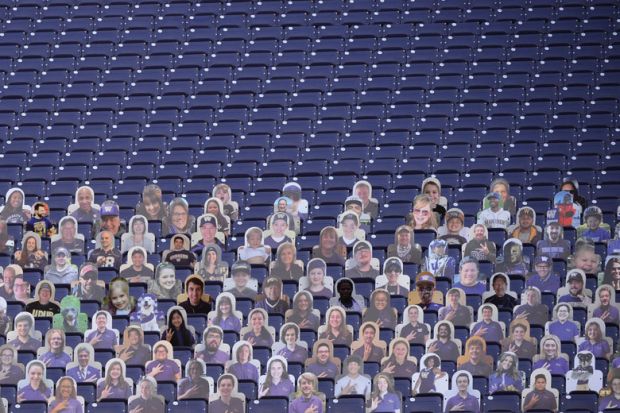

The US, by contrast, has plenty of space to welcome more students from abroad. The capacity at higher education institutions within its borders is similar to that in the rest of the top 10 hosting nations combined, offering an unparalleled variety of fields of study and majors. Ten years ago, enrolment in US colleges and universities exceeded 20 million; today, it stands at 17.9 million, as the number of 18- to 24-year-olds continues to shrink.

The US doesn’t need to invent new engines of growth. Nor do we have to build new schools or train new faculty to expand the economic and cultural advantages of international education. Everything is already in place.

So let’s aim to have not just 1 million international students enrolled by 2025, but 2 million by no later than the end of this decade. That should be the US’s international education moonshot, as we reassert our shared leadership in this industry so critical to American success.

Allan E. Goodman is chief executive officer of the Institute of International Education.