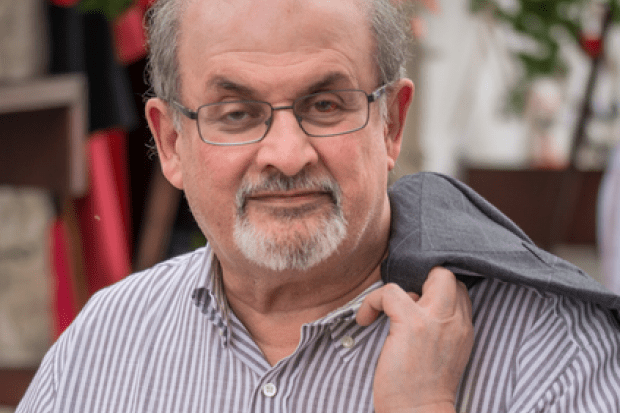

Since the horrific news of Salman Rushdie’s stabbing broke, I’ve been revisiting his lectures and interviews. I came across an article in The Observer from 1989, where he said, “Literature is where I go to explore the highest and lowest places in human society and in the human spirit, where I hope to find not absolute truth but the truth of the tale, of the imagination and of the heart.”

Rushdie’s statement about literature made me reflect on another piece of news that broke earlier this month. According to an investigation by The Times, UK universities have contracted the “harm” virus from their cousins across the pond and have started removing “harmful” literature from reading lists to protect students. Let’s take a quick look at some of the titles that have been nixed.

The University of Essex has permanently withdrawn Colson Whitehead’s 2017 Pulitzer-winning novel The Underground Railroad because of its “graphic description of violence and abuse of slavery”. At the University of Exeter, students can opt out of reading Mary Prince, the first narrative of a Black woman to be published in the UK, in 1831, to avoid the “graphic accounts of slavery”. History students at Lancaster University can choose not to read The Diary of Thomas Thistlewood, the testimony of a Jamaican slave owner, because it has details of “sexual assaults and extreme violence”. Eimear McBride’s A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, Evie Wyld's All the Birds, Singing, Thomas Meinecke’s Tomboy: the list of possible opt-outs goes on.

This notion that students may be harmed by works of literature is predicated on a profound misunderstanding of the value of literature. One does not read merely to be entertained or to have one’s world view confirmed. Rather, the reading of literature cultivates an aesthetic sensibility, a deeper sense of empathy, and the ability to see the world from different perspectives. It allows you to be taken out of yourself in a way that only art can do. Indeed, Joyce Carol Oates goes so far as to say that it is “the sole means by which we slip, involuntarily, often helplessly, into another’s skin, another’s voice, another’s soul”. Literature gives you access to people and worlds unknown.

Literature also helps you see the particular as universal. As F. Scott Fitzgerald noted, when you read, “You discover that your longings are universal longings, that you’re not lonely and isolated from anyone. You belong.” Or, as James Baldwin put it, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” Literature allows you to see how you are larger than yourself by revealing the webs that connect you with the multitude of humanity across time and space, while simultaneously making you realise your own insignificance.

In many instances, the transformative power of literature lies in its ability to shock and surprise: to jolt us out of complacency, forcing us to contend with the uncertain, the strange and even the ugly. For Franz Kafka this was the whole point of reading: In his view, “we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us...We need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like suicide. A book must be an axe for the frozen sea inside us.”

Having to contend with things that disturb us opens the door for the kind of contemplation that is necessary for growth. In that sense, scrubbing British curricula clean of the voices that give us an insight into the violence of slavery does students a grave disservice: their understanding of history will be shallow and distorted.

We would also do well to remember that one of the things offered by literature – especially of the tragic and disturbing kind – is catharsis. Rooted in the Greek kathairein (cleanse) and katharos (pure), catharsis was first used to describe the effect of a tragedy on the spectator by Aristotle in the Poetics. It is the process that allows readers to work through their anxieties and negative emotions vicariously, by identifying with characters and relating to their predicament. It allows for an emotional release that provides deeper insight into oneself. In this way, literature, far from being “harmful”, has what Maya Angelou called “life-giving power”.

Some critics have dismissed the Times investigation as a tempest in a teapot and averred that only a handful of UK institutions have begun removing “harmful” books from syllabi. But I would like to remind them that it only takes a few to begin normalising such removals before others follow suit – the recent proliferation of similar moves to “accommodate” students at American colleges and universities ought to be instructive.

As for the dons who have nixed books from their reading lists or allowed students to opt out of “difficult” literature, they would do well to reflect on Rushdie’s conception of literature as a means to “explore the highest and lowest places in human society and in the human spirit”. Ought students be spared any graphic account he might subsequently write of the low place in the human spirit to which his refusal to be silenced has reduced him?

Surely not. Depriving our students of access to the full range of human experience in the name of protecting them only, ultimately, does them harm.

Amna Khalid is associate professor in the department of history at Carleton College, Minnesota.