This year’s Times Higher Education ranking of the world’s most international universities is again dominated by countries that, through geography, government policies or culture, are open to the movement of students, staff and ideas.

From Switzerland and the UK in the West to Singapore and Hong Kong in the East, these nations owe much of their success in higher education to being hubs of internationalisation (although in the UK’s case it is now clearly a factor under threat because of Brexit).

As a result, despite some ebb and flow in the order among the top 10 – École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne takes the top spot, swapping places with its Swiss counterpart ETH Zurich – many of the institutions in the ranking are familiar.

World's most international universities: the top 20

| Rank | Institution | Country/region | Score |

| 1 | École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne | Switzerland | 97.7 |

| 2 | ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich | Switzerland | 97.5 |

| 3 | University of Hong Kong | Hong Kong | 96.7 |

| 4 | National University of Singapore | Singapore | 95.9 |

| 5 | Imperial College London | United Kingdom | 95.5 |

| =6 | Nanyang Technological University | Singapore | 95.3 |

| =6 | University of Geneva | Switzerland | 95.3 |

| 8 | University of Oxford | United Kingdom | 94.8 |

| 9 | University of Cambridge | United Kingdom | 93.3 |

| 10 | Australian National University | Australia | 92.9 |

| 11 | London School of Economics and Political Science | United Kingdom | 92.6 |

| 12 | UCL | United Kingdom | 92.5 |

| 13 | Technical University of Denmark | Denmark | 92.4 |

| 14 | King’s College London | United Kingdom | 92.3 |

| 15 | University of Vienna | Austria | 91.8 |

| 16 | University of Melbourne | Australia | 91.7 |

| 17 | Copenhagen Business School | Denmark | 91.6 |

| 18 | Delft University of Technology | Netherlands | 90.5 |

| 19 | University of Warwick | United Kingdom | 90.3 |

| 20 | University of Edinburgh | United Kingdom | 90.2 |

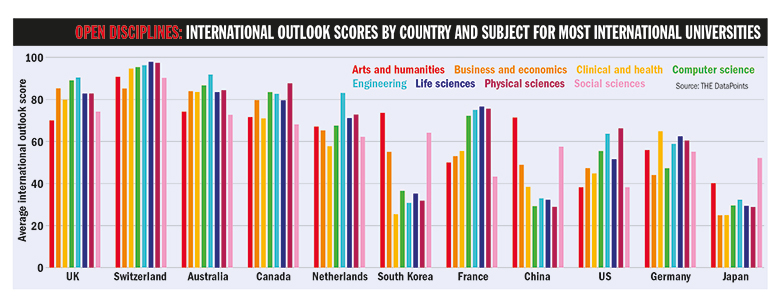

However, a new analysis by THE of the data underlying the list – which mainly consist of scores from the “international outlook” pillar of the main World University Rankings, reflecting universities’ share of overseas staff, students and cross-border research – shows that countries’ ability to be open to the rest of the world does not necessarily always cut across every subject.

While the most international universities in nations such as Switzerland are as globalised in the arts, humanities and social sciences as they are in pure science, the same is not true everywhere.

Click here to see a hi-res version of the graph

For instance, the UK’s most international universities appear to be most globalised in engineering, business and management and computer science, but much less so in the arts, humanities and social sciences. Institutions from the Netherlands, meanwhile, are strongly global in engineering, but less so in other subjects. Particularly in clinical and health subjects, they are less international than other European universities.

Most interestingly, according to the data, which are drawn from the international pillar scores in each of THE’s subject rankings, universities in Asian countries that score poorly overall for internationalisation, such as China, South Korea and Japan, seem to be more global in the arts, humanities and social sciences than in pure science – the opposite of their Western counterparts.

While a major caveat here is that the data only cover a small number of the most international universities in each country, this finding is also backed up by an analysis of wider statistics on research collaboration. According to data extracted from Elsevier’s SciVal analysis tool, almost 38 per cent of Chinese arts and humanities research indexed in its Scopus database in 2017 had an international co-author. For engineering, this figure was 20 per cent, and in physics and astronomy, it was 23 per cent.

This could be because of the types of research, journals and languages covered by bibliometric databases. But it could also be a result of other factors such as the need for Western academics studying China to work with researchers in the country.

“With the rapid development of China, there are an increasing number of Western scholars who are interested in Chinese society, culture and tradition,” said Lili Yang, a PhD researcher working on a project at UCL’s Centre for Global Higher Education comparing higher education systems.

“Further investigation into Chinese studies requires close collaboration with Chinese universities. And I personally know many examples [where] Western scholars initiated research projects to collaborate with Chinese scholars,” she added.

In terms of international students studying in China, Ms Yang pointed to elite universities encouraging more mobility into the country through schemes such as Tsinghua University’s Schwarzman Scholars, a humanities and social science programme that claims to be the “most significant of its kind” since the Rhodes Trust was set up by the University of Oxford to fund scholarships for international students.

There was a particular push to encourage more cross-border student movement as part of the Chinese government’s “Belt and Road” infrastructure project connecting the nations of Eurasia, Ms Yang said.

But what of other countries in which the most international universities seem to be more open in some subject areas than others?

In Europe, where apart from Switzerland there seems to be a fair degree of variation among subject areas in terms of global outlook, arts, humanities and social science subjects are much more likely to look at cultural and linguistic issues that apply only locally.

But this does not explain why elite universities in some countries excel in openness in certain science subjects: the Netherlands in engineering, Sweden and Denmark in life sciences, France in physics and computer science, for example. And in health research there is great variation between European nations too.

Distinct national health systems may explain this last point, with research needing to be applicable to that country. And Bart Pierik, public affairs adviser for the Association of Universities in the Netherlands, also points to labour market factors as another possible explanation. “People who work in finance or technology would be more likely to be employed by a multinational company, or at least work on issues or markets that transcend the scale of countries,” he said. “This plays less of a role for literature teachers and doctors.”

In North America, there seems to be a clearer lead for subjects like engineering, physical sciences and computer science having a global outlook.

But it is notable that this difference is much more marked in the US than in Canada, where there are relatively strong scores across the board.

One particularly eye-catching performer is the University of Alberta, which, despite being more geographically isolated than other Canadian institutions such as the University of Montreal or the University of Toronto, comes higher in the most international ranking. Its international pillar scores are noticeably very high in subject areas such as the physical sciences and computer science.

Jonathan Schaeffer, Alberta’s dean of science, said that the university’s strong global reputation in subjects such as palaeontology and computer gaming, the institution being at the forefront of the massive open online course boom, and particular characteristics of its offer to students – such as fieldwork opportunities harder to come by elsewhere – were all possible explanations.

However, he added that the general open climate in Canada at the moment was also very important and he had no qualms about Alberta taking advantage of the fallout for higher education in other countries from events such as the election of Donald Trump and Brexit.

“I would like to thank President Trump for his unique policies because they are allowing us to attract outstanding American and [other] international graduate students and undergraduates and they are also allowing us to attract some superb American faculty members,” he said.

“In both the US and Britain, politics are creating an environment which will lead to a drain of outstanding people and it is hard to imagine that that drain is going to have any positive effects.

“And I would be crazy not to try and take advantage of it. Another few years down the road…[and] the politics in Canada could become unstable and you can be sure every other country is going to be looking to Canada to try and steal people from us.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login