Thousands of university staff have joined picket lines across the UK at the start of three days of strike action over pay, pensions and working conditions.

In what the University and College Union (UCU) has described as the country’s “biggest ever university strike”, which is expected to involve more than 70,000 staff at 150 universities on 24, 25 and 30 November, union members gathered outside campuses and university buildings to protest against a national pay deal of 3 per cent for 2022-23 – rising to 9 per cent for the lowest paid – as inflation hit a 40-year high of 11.1 per cent.

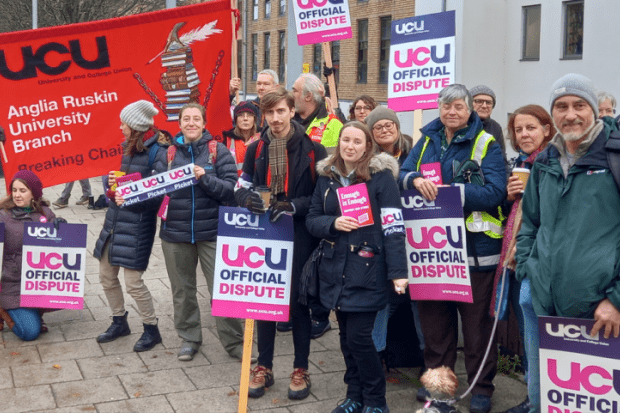

In Cambridge, about 50 union members joined a picket outside Anglia Ruskin University (ARU), with around 400 UCU members across the institution expected to walk out over the coming days before beginning “work to contract” action.

Andy Noble, vice-president of ARU’s UCU branch, told Times Higher Education that the 3 per cent deal came “nowhere close to compensating staff for the real-term cuts in pay over the past few years”.

“Our union has shown that universities have huge resources and held back large amounts during the pandemic – we just don’t accept the argument that employers can’t afford to pay any more,” said Dr Noble, a senior lecturer in employment law.

Large pay rises to senior managers and vice-chancellors, and millions held back for future infrastructure projects, showed that higher education institutions could afford to release funds when it suited them, added Dr Noble.

“It’s time some of this money came the way of staff – without them, the university cannot function,” he said.

At the University of Cambridge, pickets were also held outside Senate House, in Downing Street and outside the offices of Cambridge University Press, with some 800 non-collegiate members of staff due to participate in strike action.

Speaking outside Senate House, Eleanor Blair, a UCU representative in the department of engineering, where she is an academic-related member of staff working in IT, said the minimum 3 per cent deal imposed in August did not reflect the sector’s financial strength. “Cambridge has certainly made a lot of money over the past few years but I’d say the sector’s finances as a whole are quite rosy – there is money in the coffers for a decent pay rise,” said Ms Blair.

“Vice-chancellors’ pay certainly hasn’t stagnated in the same way as ours has,” she added, stating that salaries in university sector had fallen by 25 per cent in real terms over the past 13 years.

Staff precarity was also a major issue at Cambridge, with the Justice for College Supervisors campaign set to hold a rally on 25 November to highlight the plight of hourly paid teaching staff, said Ms Blair.

“People are doing one or two hours of preparation for the small group teaching that Cambridge is known for, but they are not being paid for this time – if they make a fuss they will not be given any teaching the following term,” she said.

Michael Abberton, president of Cambridge’s UCU branch, said the strike also reflected anger over recent cuts to the pensions of those enrolled in the Universities Superannuation Scheme.

“My pension will be cut by at least 30 per cent after the changes, but, for new starters, they will see higher than that,” said Mr Abberton. “The pension valuation was taken at the height of the Covid crisis but we’ve already shown that it is now back in surplus.

“We have record profits being recorded by some universities and money being poured in assets here – and that is happening in other universities too. We have building projects starting all the time, but we are bleeding academics out of the industry, and administrative staff too, because they see how pay and benefits are not increasing. This has to stop and this is why we are here today.”

UCU described the picket lines nationwide as “huge”, with staff telling the union they were “the biggest picket lines they have ever seen along with huge student support”.

But the Universities and Colleges’ Employers Association said initial reports were that the industrial action had resulted in “low and isolated” levels of disruption to university teaching. Raj Jethwa, its chief executive, said institutions were “proving that they have effective mitigations in place to minimise any interruption of learning or services to students and staff”.

“We respect employees’ right to take lawful industrial action, but it is misleading to their members for UCU to ask them to lose pay in pursuit of an unrealistic 13.6 per cent pay demand which would cost institutions in the region of £1.5 billion. UCU leaders must provide its members with a realistic and fair assessment of what is achievable because strike action does not create new sector money,” Mr Jethwa said.

“UCU’s own research confirms that, in many parts of the country, HE institutions are important local employers. Those communities simply cannot afford to lose jobs that an unaffordable pay uplift would risk.”

Ucea has offered to open pay negotiations for 2023-24 early but insists it will not revisit the 2022-23 deal, stating employers regarded the pay round as concluded.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login