In the US, a college degree is a central factor in social mobility. Individuals with a four-year degree earn more and experience lower unemployment rates than the rest of the population. In addition, earning a college degree is associated with greater job satisfaction and greater career mobility and satisfaction.

Most four-year colleges and universities require applicants to take one of the standardised tests designed to evaluate their academic abilities and potential for success. Yet exams such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and the American College Testing Exam (ACT) have proved to be far from objective measures. Scores are often linked to the applicant’s level of disadvantage, including their family background, race and access to economic resources.

The College Board, which administers the SAT, has acknowledged that background factors may create inequalities in test performance. In a recent effort to compensate, it has created an “environmental context dashboard”. The dashboard – which has been referred to by some media outlets as an “adversity score” – includes data about the type of neighbourhood the student is from (such as poverty level, median family income) and about their high school (such as the percentage of students receiving free and reduced-price lunches). It can be viewed by college admissions officers, but is not available to the student.

This move may be the most important step the College Board has yet taken to acknowledge the potential limits of the SAT. However, it does little to resolve many of the exam’s core problems. Perhaps most significantly, it does little to tackle the factors that drive inequality in standardised test scores.

The ways that background factors can affect standardised test performance are varied and, at times, complex. For example, prominent psychologists Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson have explored the role that stereotypes can play. Specifically, they have shown that if members of stigmatised groups are exposed to negative stereotypes about their group and its academic achievement before taking the exam, the experience may lower their test score. It is difficult to prevent this from happening given the systemic racism that pervades American society.

Other challenges may include persistent racial and economic school segregation, which creates inequality in access to educational opportunities, and racist school tracking decisions – putting students on different educational tracks based on their academic performance – that disadvantage students of colour by excluding them from college preparatory courses.

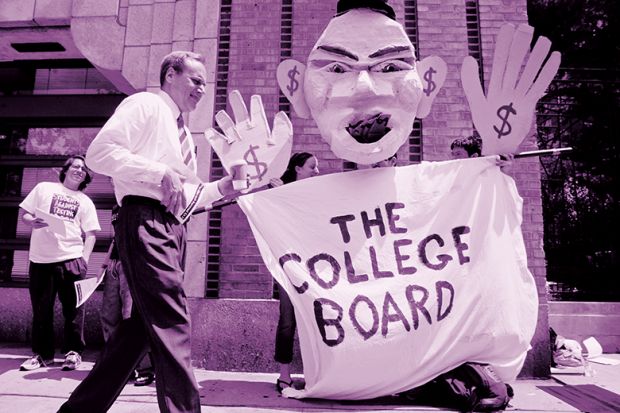

Because of its role in admissions, the College Board is one of the most powerful players in higher education, with tremendous resources at its disposal. Although it is technically a non-profit, it has annual revenue of more than $1 billion (£788 million). This is drawn largely from the administration of its exams, which also include the Pre-SAT (usually administered to high school students in 10th and 11th grades) and Advanced Placement exams (subject-area high school exams, high score in which can be used for college credit). If the College Board is truly committed to ameliorating inequality, it could devote more of its resources to improving the quality of education that students receive before college. This might include helping to diminish inequalities in access to educational opportunities and working to end school tracking.

There is also significant potential for abuse of the environmental context dashboard. Because it flags inequalities, it also highlights factors that are often used to discriminate against people. For example, drawing more attention to neighbourhood context could make it easier to discriminate against students from particular types of areas. The information in the dashboard can also be used to create stereotypes about students based on background characteristics. Biases can often operate at the subconscious level, so even seemingly well-intentioned admissions officers may misuse information in a way that penalises students.

The fact is that because they are influenced by a number of factors that have nothing to do with academic ability, standardised tests are fundamentally flawed. Adding an environmental context dashboard that admissions staff can use at their discretion to interpret a student’s scores does nothing to change this. Research has shown that other components of a college application, such as high school grades, may be better predictors of success in higher education. Thus, if the goal is to truly level the playing field in admissions, the elimination of standardised testing altogether would be far more productive.

In fact, a number of colleges and universities have taken this route, making the SAT and ACT optional. They have observed no change in their student performance; recent research confirms that they have maintained rigorous academic environments while diversifying their student bodies.

Thus, while the College Board may believe that the addition of its environmental context dashboard is an important step towards ameliorating inequality in the college admissions process, it serves to highlight the problems with standardised tests. As a result, questions about their usefulness have become more significant.

When scores need to be explained by a host of factors that are outside a student’s control, it is time to look towards other ways to measure academic achievement and potential.

Jessica Welburn Paige is assistant professor of sociology and African American studies at the University of Iowa.

后记

Print headline: Standardised admissions tests can’t be redeemed by extra contextual data